42 Amens

|

Walt Mundkowsky [June 2009.] But wherefore could not I pronounce “Amen”? — Macbeth, II, ii

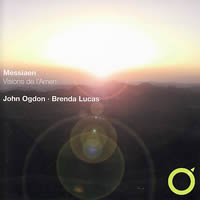

Olivier MESSIAEN: Visions de l’Amen (1943). Yvonne Loriod, Olivier Messiaen (pnos). Dial LP 8 (1950 LP, private recording onto CD). On disc via Future Music Records FMRCD120-L0403 (http://www.fmr-records.com/). “From Mozart to Messiaen.” Visions de l’Amen* (1943). John Ranck*, Irén Marik (pnos). Arbiter 152 (2 CDs) (http://www.arbiterrecords.com/). Distributed in the US by Qualiton (http://www.qualiton.com/). Also DEBUSSY, BARTÓK, LISZT, MOZART, BEETHOVEN, SCHUBERT, BRAHMS, SCHUMANN. Visions de l’Amen (1943). Yvonne Loriod, Olivier Messiaen (pnos). Accord 465 791-2 (http://www.universalmusic.fr/). Also Cantéyodjayâ (1948). Visions de l’Amen (1943). Yuji Takahashi, Peter Serkin (pnos). RCA ARL 1-0363 (1973 LP, private recording onto CD). Visions de l’Amen (1943). John Ogdon, Brenda Lucas (pnos). Explore EXP 0013 (http://www.explorerecords.com/). Distributed in the US by Koch Entertainment (http://www.kochdistribution.com/). Visions de l’Amen (1943). Alexandre Rabinovitch, Martha Argerich (pnos). EMI CDC 7 54050 2 (O/P). (ArkivMusic offers a dub.) Background With Marcel Dupré’s backing, Messiaen left the Silesian prison camp in March 1941 and found work at the Paris Conservatoire as professor of harmony. He also saw his muse in a piano student who attended his first class (May 7), Yvonne Loriod. (“I was therefore able to allow myself the greatest eccentricities because to her, anything is possible.”) He wrote Visions de l’Amen for them to play together. Layout Both ingenious and eminently practical. Piano I (Loriod’s) gets “the rhythmic difficulties, the bunches of chords, everything concerned with speed, allure and quality of sound.” An experienced organist, Messiaen keeps back “the principal melody, the thematic elements, everything demanding emotion and power” for Piano II. Within the star duos to come, the bigger “name” hasn’t always taken Piano II. Seven Messiaen had already developed a related plan, for Les Corps glorieux (1939). The seven Amens start in Genesis and finish with Revelations; Amen du Désir, the longest and most personal, lies at the center. Between I and IV, a Harmony of the Spheres and Jesus on the cross. V has the angels, saints and birds (“Some of the best songsters,” Messiaen calls the last), and VI is a curt rejection of the damned. This is one of those pieces which, once you have become hooked, will have you looking at all the other desirable versions around.— Dominy Clements Recordings Messiaen: Visions de l’Amen (1943)

Loriod / Messiaen 1, rec. 1949

In the published score (1950) Messiaen lists 35 concerts, so Amen had settled by the time they first recorded it. Still, the urgency and risk impart a more moderne feel than it would later have (Darmstadt was among the duo’s stops), and deflate the more gaseous episodes a bit. Some familiarity or a score may help separate the two pianos; elsewhere, the dulled colors and dynamics emphasize the linear aspect. Amen de la Création has the Deity on a tight schedule, and Amen du Jugement flashes cutting authority despite its mild lightning bolts. Hans Rosbaud’s 1951 Turangalîla-Symphonie (Wergo WER 64012) would be the apt comparison — a brave path no one chose to follow. [Thanks to John Blackley (Schola Antiqua) for his invaluable assistance. W.M.] Ranck / Marik, rec. 1956 This is a major find — detailed, wide-ranging sound by Zodiac Records’ Lee Erwin (but never released) and a penetrating gaze into Messiaen’s ethos. Rhythmic acuity is matched by emotional breadth. Though deliberate, Amen de la Création and the finale Amen de la Consommation never loosen their grip; the first reaches awe peu à peu, while the latter is knowingly paced so its reiterations add weight, not tedium. Désir is truly the centerpiece, a chanté, expressif et tendre immersion after the savagery of II and III. Jugement might be profitably less rounded-off (fleeting dropouts on the tape don’t hurt). Applause comes as a shock, so ideally attentive has been the audience. Loriod / Messiaen 2, rec. 1962 Thirteen years after their first, les créateurs took another approach with better sound. The less-headlong tempos can’t be termed a relaxation, but they do allow a clearer window on the playing. The composer is solide et décidé but not above liberties, and Loriod’s skill at on-the-fly tweaks is as thrilling as her glittering canons. What’s unchanged from the 1949 recording is the quality of belief — en pleurant amidst the brutality of Amen de l’agonie de Jésus, uniting the grande tendresse and très passionné in Désir. The stereo separation conveys the basics and no more, but could the harsh colors reflect a conscious choice, not merely a 47-year-old tape’s limitations? Unknowable. Takahashi / Serkin, rec. 6 / 70 Serkin’s affinity for Messiaen is undoubted (Quatuor with Tashi; Vingt regards), and his partner gets Piano I’s requirements as well as anybody post-Loriod. What’s missing? The thing itself: RCA waited three years to release the LP, and a 1999 CD had the lifespan of an insect. Producer Max Wilcox ensures a wide, seductive array of color, and the delivery is highly refined. Création’s gradual buildup never hurries, so the cut-off ending carries a real sting; Consommation sustains interest through lovely dynamic gradations. Amen des étoiles has less grit in the gears than usual, but within its spectrum doesn’t lack force. The space between pianos heightens the splendid ensemble. Ogdon / Lucas, rec. 12 / 70 I learned the piece from this recording (Argo ZRG 665, 1971), so I’m happy to find it on disc, along with notes by Messiaen authority Robert Sherlaw Johnson (1932-2000). Much has happened to Amen in the past 38 years, but this duo’s commitment shines through the greyish palette. Curiously, Ogdon sits at Piano I (he seems a natural for II), which tips the balance now and then — as it provides a new slant. Jugement is superbly in sync, even in oddly muffled blows. Where blunt power can cover some plodding (Amen des étoiles, de l’agonie de Jésus), results are good. Désir stretches out, but Consommation has the right joyeux air and reaches the finish with plenty of punch. Rabinovitch / Argerich, rec. 12 / 89 Rabinovitch-Barakovsky (current usage) gave the first Vingt regards in Russia, before he moved to France in 1974. Per the chart, he and Argerich plot a unique course. Synchrony impresses where it’s mandatory, but poetic elevation is the aim. Amen des étoiles is more frenzied than grinding, and the statement of the big theme (start of Amen des anges) gets mysterious de-emphasis. (Argerich scores here with voluble chirping birdsong and pearly runs.) Consommation’s ecstasy translates into motion and color, while the quieter side of Désir can be realized in hesitancy and suspension. The ’80s digital recording falls short; a jump in volume won’t eliminate the veils and distance. Another 42 Amens will follow, someday. We are individual stones in a mighty edifice, whose completed design we shall need more time and more peace to see in its proper perspective.— Antoine de St. Exupéry (1942)

[More Walt Mundkowsky]

[More

Messiaen]

[Previous Article:

Mostly Symphonies 11.]

[Next Article:

Six Curious Pair Bonds]

|