Proliferating Prometheus

|

[With gratitude to Judith Pfahnl for her friendly assistance and to Nuria, as always, for her support. D.A.] Dan Albertson [March 2009.]

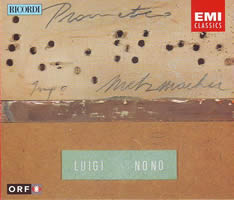

Luigi NONO: Prometeo, Tragedia dell’ascolta (rev. version) (1981-84, rev. 1985). Petra Hoffmann & Monika Bair-Ivenz* (sop), Susanne Otto* & Noa Frenkel (alt), Hubert Mayer (ten), Sigrun Schell (fem spkr), Gregor Dalal (male spkr), Martin Fahlenbock (picc, fl, b fl, cb fl), Shizuyo Oka (picc cl, cl, cb cl), Mike Svoboda (a trbn, b tba, euph), Barbara Maurer (va), Lucas Fels (vc), Ulrich Schneider (db), Christian Dierstein, Klaus Motzet & Jochen Schorer (glasses), 12 voices of the Solistenchor Freiburg*, ensemble recherche, Solistenensemble des Philharmonischen Orchesters Freiburg, Solistenensemble des SWR Sinfonieorchesters Baden-Baden und Freiburg, Peter Hirsch (1st cond.), Kwamé Ryan (2nd cond.), Experimentalstudio für akustische Kunst, André Richard*, Reinhold Braig, Joachim Haas & Michael Acker (live electronics), Bernd Noll* (technician). (* denotes personnel from première of the orig. version, 9/1984) col legno WWE 2 SACD 20605 (http://www.col-legno.com/). Distributed in the US by Allegro Music (http://www.allegro-music.com/). Ingrid Ade-Jesemann* & Monika Bair-Ivenz* (sop), Susanne Otto* & Helena Rasker (alt), Peter Hall (ten), Évelyne Didier (fem spkr), André Wilms (male spkr), Dietmar Wiesner (picc, fl, b fl, cb fl), Wolfgang Stryi (picc cl, cl, cb cl), Benny Sluchin (a trbn, t-b trbn), Gérard Buquet (b tba, euph), Charlotte Geselbracht* (va), Helmut Menzler (vc), Thomas Fichter (db), Boris Müller, Rumi Ogawa-Helferich & Rainer Römer (glasses), 12 voices of the Solistenchor Freiburg*, Ensemble Modern, Ingo Metzmacher (1st cond.), Peter Rundel (2nd cond.), Experimentalstudio der Heinrich-Strobel-Stiftung des Südwestfunks Freiburg, André Richard*, Hans-Peter Haller*, Rudolf Strauß* & Roland Breitenfeld (live electronics). (* denotes personnel from première of the orig. version, 9/1984) EMI Classics 5 55209 2 (O/P). I must start with two confessions. The first is that any words, no matter how eloquent, will fail to convey what Prometeo is or what its experience means. The second is that this essay is founded on an academic conceit, because the Metzmacher recording is long gone (like, alas, most of his superb EMI catalogue) and is to be found only occasionally at musical antiquaries for highly inflated prices. The new col legno issue is, thus, assured in its place as “recommended recording.” Prometeo is a work from Nono’s last phase, the grandest manifestation of his intensive research into the possibilities of live-electronic transformation and the exploitation of aural extremes. Much of its music lies at or beyond the fringe of what the human ear will translate; the prevailing mood is bleak and stark, yet with the constant prospect and occasional realization of a sudden sunny spell. Its 1984 Venetian première was an event uniting many figures from various strands of Italian cultural life, beginning with one of his oldest friends, visual artist Emilio Vedova, proceeding to an ardent champion, conductor Claudio Abbado, and to two new kindred spirits, philosopher (and later Venezia’s mayor) Massimo Cacciari and architect Renzo Piano. The latter has spoken of the tremendous efforts involved in designing a space apposite to and unique for this piece, a miniscule world within our world meant for music seemingly not of our world. The composer, ever self-critical, was not satisfied with his musical contribution and undertook extensive revisions; this version is the only one revived these days and revived it is, against all odds. I recall a Spanish performance from a few years back and its London début in 2008 moved many a critic and listener. Replicating the sanctuary of Renzo Piano is impossible, but these two recordings give at least a semblance of how and what the experience could or should be. Both Metzmacher and Hirsch have assembled musicians, singers and/or electronics specialists who had collaborated with Nono extensively in his last years — an element of authenticity, but even more a necessary recognition that much of his vision resides in them and not in the score, as usual in Nono’s output. Both recordings feature Susanne Otto, the singer who meant more to Nono than any other in the 1980s, and both have the complex electronics overseen by André Richard, a faithful collaborator. Differences in general are slight, but some are more meaningful. Brass entries in the Hirsch recording tend to be less powerful, sapping the work of some of its most surprising moments in the Prologo and Isola Prima. Metzmacher has a better understanding of the import of these brass fanfares, no doubt harkening back to the Gabrielis revered by Nono, and ensures both their proper dynamic and place within the soundscape. Another disappointment in the Hirsch reading is in Hölderlin, a brief moment of repose in which female voices float, sometimes overlapping and sometimes isolated. Metzmacher hears this section with much more fluctuation, the voices constantly in flux; Hirsch prefers a homogeneous approach, his voices more stable and less fragile. As a result, the profound impression of ephemerality tinged with a melody eerily similar to a lullaby, with the voices fading into the ether at its end, is less memorable in Hirsch, who as an assistant to early performances of Prometeo, has more of a pedigree than Metzmacher. Nono: Prometeo, Tragedia dell’ascolta (rev. version) (1981-84, rev. 1985)

Tempi differences are slight, as the chart above demonstrates, and the work creates a universe in which “human time” becomes more and more impossible to elucidate. I truly had no sense that Hirsch was slower at first and faster toward the end. The live acoustic for Metzmacher is less warm in its frequent ppppp moments, but Hirsch seems more restrained with his musicians, softening the loudest outbursts and, using the more responsive acoustic to his advantage, keeping the work more in the middle-to-low range of dBs. The col legno team of engineers, technicians, et al., with its SACD technology, must have the edge in clarity, though EMI is far from roiled. Both sets of vocal soloists excel in their contributions, with a beauty of sound finely attuned to the instruments and to the electronics, which enhance and never overwhelm the musicians. The only instrumental difference is that Hirsch has a single virtuoso capable of sharing the varied brass requirements, in the manner of the work’s original brass soloist, Giancarlo Schiaffini. I am not the greatest devotee of electroacoustic inventions, but in Nono electronics and humans may have met their perfect master: He has obliterated the barrier separating the two, engendering an environment of flurries and palpitations, silences and thunderclaps. Prometeo has some slightly inconsistent moments, not deleterious to the whole but also never resolved. The mixed speakers in both works fail to make much of an impression, perhaps by intention; Nono ends their involvement in the work before the first hour has finished. One must wonder, though, if Nono had bigger intentions for these rôles. Why else would he engage Heiner Müller, one of Germany’s finest dramatists, as speaker in its first performance? As an alternative, was Müller “too much,” compelling Nono to lessen the speakers’ contribution in the revised edition? Further, Nono has here abandoned his earlier emphasis on the centrality of the “logos” of texts, instead preferring text as sound. Aesthetic views are apt to evolve, and Nono’s only grew richer and more meaningful as he aged, but the work has no dramatic impulse because its words are not easily deciphered and one must wonder why so much effort was spent on its multilingual libretto, drawn predominantly from Ancient Greek sources, but also from German poets of the recent and distant past. Whichever recording is acquired, some listeners will find the work too long, or too boring, or too monotonous, or too peregrine, but such listeners are looking for the wrong measurements of musical worth. At around 135 minutes, “long” is not the correct adjective. The question of boredom is relevant, because the modern-day listener tends to be impatient and many composers have attempted to fill their spaces with “as much” in “as little” as possible. One must prepare for the work by remembering that time is always relative; one should be ready to lose oneself in what is to follow and not to expect any immediate answers. Questions are more important than answers, as Edmond Jabès would aver. Monotony is never a possibility, nor are fears of a music so peregrine that “oneness” is unachievable, because Nono is acutely aware of proportion and varies the instrumentation of each section, never neglecting to create the sense of overall structure essential for a work of such duration to be strong, my few previous reservations excluded. The final 20-25 minutes are of a hushed, empyreal nature, with the earlier interjections nowhere to be heard. Nono has written music of utmost expression and mystery here, a coda almost too sublime in its tenderness. In terms of documentation, the col legno set is preferable. EMI features a brief overview of each movement and comes with copious photographs, score excerpts and complete texts. col legno has fewer photographs, but a more thorough survey of the work by scholar Lydia Jeschke and complete texts with annotations by Klaus Pauler, a so-called “listening score.” These annotations prove quite helpful if one is interested in understanding the heart of the work; other listeners may well prefer the piece as “pure sound.” No listener will be led astray by purchasing the col legno set and for those with SACD equipment, which I lack, the experience must be even more profound than in stereo. Nono is never one to seek cheap thrills or easy solutions. His music is unremittingly, unashamedly modernist, ever longing for a new means of celebrating and doubting the precepts of musical production and reception. Prometeo is astonishing, a work more prophetic in its attractive desolation than the composer could have known.

[More Dan Albertson]

[More

Nono]

[Previous Article:

Mostly Symphonies 10.]

[Next Article:

Dowland Our Contemporary: String Quartets]

|