A Catalogue of Darknesses, Part 1.

|

Dan Albertson [January 2018.] [What better way to greet a new year, or indeed any year, month, week, or day, than to obsess over works of melancholy? And yes, why can darkness not have a plural? The premise of this new series is to spill a few words about songs from different centuries that I find notable for their grasp of this disposition. Fake-sad need not apply. This catalogue will by no means be encyclopedic; I intend it as glimpses into a vast reservoir. Thanks this time go to Fang Ge, for his intrepid curiosity.]

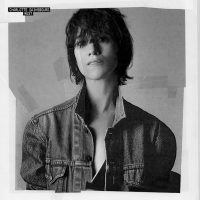

Charlotte GAINSBOURG: Ring-a-ring o’ roses (2017) Easily the highlight of her overhyped album Rest, the opening number associates anew the round with the macabre, even if no one knows the real backstory of the timeless rhyme. In a mix of English and français, a trademark reflecting her parentage, she sings and whispers her way atop a relentless tapestry. A passacaglia for the electronic age? Uncommon in its pensiveness despite the “busyness” of the accompaniment, this one shows what the rest of the album could have been had its techno nuovo ambitions and production values not left it mired in the ’80s. * * * Modest MUSSORGSKY: Skuchai (Boredom) from Bez Solntsa (Sunless) (1874) The entire cycle of six songs is a marvel, even its major-key songs showing an abandon in pursuing despair. The fourth follows on from a description of a festival. The tumult of Petrushka it is not. Apparently written in late spring, the prime of the year, its languor is an aural antecedent to the sort of calm that pervades Parsifal. Though sexless in its instrumentation, for my ears it never works with a woman as the singer; it needs the heft of a Slavic bass. Mussorgsky’s other cycle of a hopeless bent will feature later in the series. * * * Michel LAMBERT: Vos mépris chaque jour (1689) An air de cour typical of this long-lived 17th-century Frenchman yet atypical for its time, the vogue for this type of song having passed with Louis XIII, it consists of a vocal part and an extremely sparse line for the continuo. For the persnickety: A similar melody turns up in one of Louis Couperin’s keyboard suites, which predates Lambert, and later in Acis et Galatée by Lambert’s roguish son-in-law Jean-Baptiste Lully. Ideal for me at a slow tempo, sung by a tenor with agility and lute to keep the vocal line company, its message is ambiguous, some sort of precursor to sadomasochistic tendencies that would flourish only in subsequent centuries. Vos mépris is not alone in this regard, of course, but it is an exquisite example: There is no pleasure without pain, and maybe even no pleasure, just pain.

[Previous Article:

String Theory 25: 12 Quartets, etc.]

[Next Article:

Used Bin Troll Tweets EE.]

|