A Look at Chopin’s Piano Sonata in B-flat minor, Op. 35

|

Beth Levin [January 2015.]

I: Grave Like a graveyard bell a long-held octave in D flat plummets a 7th below and heralds the opening of the first movement. Next an accented chord – C#-G#-C# – still in the bass slowly resolves to the V of I and suspends us there momentarily – so much foreboding in the span of four measures. The resolution at measure 5, doppio movimento, or double time, grows out of the introduction organically into an agitated romp as if through a dark forest. Measure 7, agitato, offers snippets of melody over broken chords in the bass. Rests between the small figures add to the breathless quality of the music, to the motion and angst. Not until measure 42 does Chopin break into a fully sustained melody in the relative major key of D flat. The performer is urged to summon legato, a singing tone and the roundness necessary to express this rare beauty, not to ignore the rich bass supporting the top. Measure 69 begins a change of direction and an emotional climb achieved through the color of intensified harmonies, arriving at measure 81. Here we experience the power of driving chords in quarter notes which are even more effective arriving after such a glorious singing melody, as if poignancy had given way to a new-found confidence. After a repeat of the exposition Chopin borrows from his opening material at measure 105. Even though the fragments are short and crisp, they are nevertheless melodic and worthy of a long line. We are in a transition from measure 105 to 137 when Chopin achieves a climactic arrival still using the snippets of melody but now with grandeur, introducing chords as triplets in the bass for added sonority and keeping the dynamic level at fortissimo. At measure 165 this motivic material winds down via a long decrescendo to reach, at measure 169, the narrative or sustained melody that we first encountered at measure 42. Originally in D flat or the relative major of B-flat minor, the same melody is now presented in B-flat major. If this were Schumann we might think of the two sections – active and narrative – as two opposing characters. But in Chopin I think the distinction is subtler and gentler, less programmatic. A powerful stretto at measure 229 propels us to the final B-flat major chord. II: Scherzo Eighth notes in octaves, in 3/4, inside a crescendo drive toward a heavy chord at the second measure but an accented third beat seems to waylay the motion. It imbues the Scherzo with a stomping, boots-to-the-floor feeling. Chopin mazurkas highlight the second beat of triple meter and here he manipulates the rhythm in yet another way. The accents, crescendi, a dynamic of forte and the 2-note slurs at measures 9 and 29 combine to achieve a powerful, propelling opening. Chords in 4ths at measure 37 dart along the keyboard in a manner worthy of any Chopin étude. This virtuoso feel to the writing continues to add brilliance to the Scherzo movement. As a double dose of heaven, in measure 81, marked piu lento, Chopin dissolves the sonata into a pool of melodic repose. We want to shout genius! on hearing such a pure, upward reaching line made even more poignant by low chords at measure 90 that surge down and away from the melody. Bach’s influence can be felt at measure 145 where the middle and bass voices reign, demonstrating how fluidly Chopin weaves in and out of the lines. A short transition at measure 184 brings us back to the original, furioso Scherzo material and to the end. Just there Chopin reminds us as in a daydream of the purely spun melody and proceeds to end in the major key, forestalling the inevitable. III: Marche Funebre Common time (4/4), piano, bass clef: A single B flat in a dotted rhythm over slowly swaying chords in the bass that never waver – a hearse moving through cobblestone streets – this is the image we associate with Chopin’s march. At measure 11 the melody turns to high octaves, descending now yet always maintaining the dotted rhythm – short-long/short-long of the opening, never straying from tempo and mood. A shift at measure 15 to ascending chords occurs in the relative key (D-flat major) and in forte that elevates melancholy to nobility. At measure 31 Chopin moves seamlessly to yet another divine melody (of which there is never a shortage). Its simplicity and serenity contrasts to, and complements, the march section as it carries us away to a dream-like place. Pianists are often chided for being altogether too “right-handed” in Chopin’s melodies and ignoring the bass or accompaniment. It is easy to do, but here the two voices, treble and bass, work as a duet, sometimes matching eighth for eighth. The voices, being far apart, make it easy for the melody to sing out without sacrificing the bass line. Chopin returns verbatim to the opening material (A-B-A), and, unlike movements I and II, maintains his original minor key to the very end. IV: Presto Frederic Chopin was giving a recital in 1848 when he left the stage midway through his Piano Sonata in B flat minor. The composer had just spotted “cursed creatures” emerging from underneath the half-open lid of the piano. In fact, he was often tormented by visions, and this week the journal Medical Humanities suggested that he had temporal lobe epilepsy, which produces just the sort of “complex visual hallucinations” that scared him witless during that recital. – Damian Thompson, The Telegraph1 Sotto voce e legato The finale is entirely composed of running triplets in unison, right and left hand playing the same note an octave apart. Chopin surges in and out of harmonies related closely to B-flat minor and highlights particular notes in a given measure by hinting at snippets of melody. The music unfolds in a great arc of color, motion and sweep. One is reminded of an hallucination owing to the music’s lack of obvious form – as if no bar lines or structure existed. Arthur Rubinstein called it “wind howling around the gravestones.” Chopin had long since left the major key behind. A loud B-flat minor chord ends the work.

[ArkivMusic shows 209 entries for Chopin’s “Funeral March” sonata. The immortal accounts – Cortot, Kapell, Lipatti, Rubinstein, et al. – scarcely require touting. Leonard Shure’s 1956 Carnegie Hall rendition (Doremi) has piercing intellect, zero mush and a 21:29 span. (A much later Jordan Hall performance, on Bridge, takes 24:39 and is less secure.) These days I’m much taken with Edna Stern’s on an 1842 Pleyel (Naïve). W.M.]

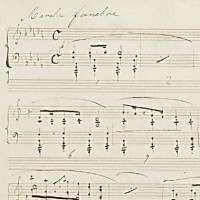

1Courage, not madness, is the mark of genius, http://blogs.telegraph.co.uk/culture/damianthompson/100050942/you-don%E2%80%99t-have-to-be-mad-to-be-a-genius/, January 25, 2001, accessed January 8, 2015. Music manuscript from http://conquest.imslp.info/files/imglnks/usimg/9/94/IMSLP80861-PMLP02363-op_35_sonata_no_2_autograph.pdf.

[More Beth Levin]

[More

Chopin]

[Previous Article:

Acoustic Revive’s Triple-C Finemet Interconnects and Triple-C SPC Reference Speaker Cables]

[Next Article:

Mostly Symphonies 26.]

|