A Surprise in ‘Most Every Box

|

Grant Chu Covell [July 2004.]

“Jardins Suspendus.” Pierre MARIÉTAN: Quaternio I (1970); L’eau sourd, bruit, chante… (1984); Quaternio II (1979); Jardins Suspendus 4 (1996); Quaternio III (1981); Jardins Suspendus 1, 2, 3 (1996); Quaternio IV (1982). Terra Ignota TI 35-98 (http://www.terra-ignota.com/). Distributed in the US by CDeMUSIC (http://www.cdemusic.org/). I had to track down more Pierre Mariétan after covering the two-disc cornucopia Ensemble Neue Horizonte Bern: Historische Aufnahmen, 1968-1998 (Musikszene Schweiz MGB CTS-M 76). Mariétan’s music connects marvelously with the natural world: Some pieces are meant for the outdoors while others coyly inveigle natural sounds into a concert setting. Produced in conjunction with a 1999 Swiss Mariétan exposition, this obscure 1998 Terra Ignota CD documents several installations and projects. The release fascinates despite the track listings having been buried in the French-only booklet. (Terra Ignota’s website similarly confounds.) The most straightforward entry, L’eau sourd, bruit, chante…, is an electroacoustic piece derived exclusively from water sounds. No thunderstorm or drowning clichés for Mariétan: His water music conjures magical fountains or Homer’s wine-dark sea. The Quaternio series are carillon pieces written to celebrate birthdays. All four are for girls (children? nieces? granddaughters?). Played by Renaud Gagneux at St. Germain l’Auxerrois, Paris, they range from four to seven minutes. Bright and arrhythmic with short melodic fragments and bursts of arpeggios and clusters, they’re meant to be heard outdoors or from a distance, like church bells. Outdoor city noise is just barely audible. You might want to broadcast these from one room and listen in another. Representing three versions of a Hermann Hesse poem, Jardins Suspendus 4 is an austere depiction of winter for voice, sticks, dead leaves and double bass. The bass whines over rustling dried foliage. A voice mimics a bitter wind as a mid-Fifties radio-play sound effect might. The remaining seasons overlap in the single-movement Jardins Suspendus 1, 2, 3. Spring mixes falling water with “I love you” spoken in many languages. Natural sounds (bees, crickets, birds) combine with man-made noises (a brass instrument imitating an elephant, a loud whooshing sound moving across the stereo space). Summer releases long tones from horn, violin, saxophone and double bass over a gentle backdrop (a distant barking dog, light rain, passing cars). Fall is fashioned from voices chanting in a Tibetan style. The whole piece ends gently with street noises and car horns. There’s a picture of a bearded, bright-eyed, wild-haired Mariétan toying with what might be one of his musical installations. The picture and the music reinforce the impression of a fun-loving inventor, perhaps a continual source of amusement to his family. In fact, two other Mariétans participate in this delightful disc: Anne, violin, and Thierry, double bass. Mariétan senior is quite a gem.

Mauricio KAGEL: Transición II (1958-59); Phonophonie (1963-64). Aldo Orvieto (piano), Dimitri Fiorin (percussion), Alvise Vidolin (tapes, electronics), Nicholas Isherwood (bass), Stefano Bassanese (tapes, sound direction). mode 127 (http://www.mode.com/). This mode release is a colorful quilt spread out for a lazy summertime picnic. Twigs and ants will drop in unexpectedly, a children’s ball will roll on by, and someone will spill the wine. These two works predate Kagel as the self-conscious music historian. We meet instead a proficient avant-garde dabbler. Keys to these performances are two completely new electronic backdrops, created according to Kagel’s instructions by Alvise Vidolin for Transición II and Stefano Bassanese for Phonophonie. Transición II requires pianist and percussionist to labor at the same piano against a pre-recorded tape of themselves and a tape created during the performance. Aldo Orvieto (piano) and Dimitri Fiorin (percussion) demonstrate solid understanding of Kagel’s intentions, though this recording belongs to master-architect Vidolin at the electronics. Phonophonie is a tour de force for Nicholas Isherwood, with his four theatrically scripted mini-dramas. Isherwood is accompanied by offstage voices, instrumental sounds and Bassanese’s pre-recorded tapes. Mode characteristically captures an energetic performance, though we’re probably missing subtleties that can only be savored live. Pierre BOULEZ: Rituel in memoriam Maderna (1974-5); Notations I, II, III, IV (1980); Notations VII (1998); Figures-Doubles-Prismes (1963/68). Orchestre National de Lyon, David Robertson (cond.). Naïve MO 782163 (http://www.naiveclassique.com/). Distributed in the US by Naxos (http://www.naxos.com/). Boulez’s Rituel in memoriam Maderna commemorates an important 20th-century composer and conductor, Bruno Maderna, a stalwart of the mid-century’s avant-garde. Progressing independently, eight groups deliver alluringly shaped phrases: Jerky grace notes frame a held note. The composition is instantly recognizable even though no two recordings can sound alike. David Robertson and the Orchestre National de Lyon craft a neat and clear performance. This is the most recent and crispest recording available. Arch polemicist Boulez is most approachable in Notations. Extroverted and concise, these steroid-enhanced orchestrations of piano miniatures make both orchestra and audience sweat. Imagine every Debussy and Ravel orchestral work macerated and reconstituted to fit within a framework of just a few minutes. Boulez has so far completed five out of a projected dozen. Characteristically he’s finished them out of order. Get on with it, Pierre! They’re to be performed in a sequence that disregards their numbering (I, VII, IV, III, II or I, III, IV, VII, II). This recording is the first to encompass the extant five. Notations VII, the most recent, premiered in 1999. Years ago I heard the first four live and no recording can match that invigorating experience. The textures’ intensity and richness were mesmerizing, instantly ricocheting from thin solo lines to deafening massed blocks and back. Other worthy collections containing the first four Notations are led by Barenboim (with Rituel on Erato 2292 45493 2) and Abbado (DG 429 260-2). Barenboim and the Chicago Symphony Orchestra premiere Notations VII on Teldec 8573-81702-2 with a brittle Rite of Spring and dehydrated La Mer. Two East-coast music critics folded this into their “Best of 2003” lists. Possibly Boulez’s halo blinded them. In any event, they appear eager to recognize that someone besides the composer-conductor might be capable of conducting this music. Robertson deserves his due, but this Figures-Doubles-Prismes noisily asserts its inaccessibility, failing to satisfactorily convey the work’s special seating plan, a fault I find with all extant recordings. I’ll happily listen to just Rituel and the five Notations.

“Wheel of Emptiness.” Jonathan HARVEY: Wheel of Emptiness (1997); Tombeau de Messiaen (1994); Ricercare una Melodia (1984, in versions for oboe and trumpet); Advaya (1994); Death of Light / Light of Death (1998). Ictus, Georges-Élie Octors (cond.). Cyprès CYP5604 (http://www.cypres-records.com/). Another winning Ictus release from Cyprès, presenting a well-rounded all-Harvey disc. Harvey is probably more familiar than either Keiko Harada or Georges Aperghis, whose Ictus / Cyprès products were discussed here and here. Bridge, Naïve Montaigne, Nimbus and Sargasso have released all-Harvey programs; the deservedly anthologized Mortuos plango vivos voco is an electroacoustic classic. In the invigorating 14-minute Wheel of Emptiness, 16 musicians shuttle between pandemonium and repose. Emphasizing the music’s harmonic spectra, the electronics infrequently surface — you may forget they’re there. At 22:15, Advaya (for cello, keyboard and electronics) is the longest piece. Its electronics are derived from cello sounds transformed in enticing episodes. We have all endured tape-delay systems abused by mediocre keyboard players at malls and subway stations: a dull chord progression or arpeggio wash forming a numbing canon. Harvey’s Ricercare una Melodia may be the best work ever for tape delay, here played by oboe (Piet van Bockstal) and again by trumpet (Philippe Ranallo). The wind instrument initiates a five-part canon, each gesture and phrase fitting perfectly with what has gone on before and is yet to come. You wouldn’t know it to be a canon unless you were told — it’s that good! Tombeau de Messiaen is a bright dialog between a taped piano tuned to the harmonic series and live piano, here taken by Jean-Luc Plouvier. The different tuning systems create a bizarre atmosphere. Each of the five movements of Death of Light / Light of Death represents a character in Grünewald’s Isenheim Altarpiece. The music was commissioned by the city to be performed in front of the legendary triptych. With elaborate oboe double-tonguing, gritty sul ponticello and grating strings, the deceptively meek ensemble of oboe, harp and string trio (I hear tam-tam too) plunges into Mahlerian despondency.

“Black Earth.” Fazıl SAY: Black Earth (1997); Sonata for Violin and Piano (1997); Concerto “Silk Road” (1994); Two Pieces for Piano and Chamber Orchestra: “Silence of Anatolia,” “Obstinacy” (2001); Paganini Variations (1995); Dervish in Manhattan (2000). Fazıl Say (piano), Laurent Korcia (violin), Orquestra de Camara Gulbenkian, Muhal Tang (cond.); Orchestre National de France, Eliahu Inbal (cond.); Kudsi Erguner Quartet. Naïve V 4954 (http://www.naiveclassique.com/). Distributed in the US by Naxos (http://www.naxos.com/). Young piano firebrand Fazıl Say has delighted audiences with repertoire ranging from Mozart to Gershwin. He has recorded Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring in a multi-tracked piano arrangement (Teldec 8573-81041-2). Say also has jazz chops, demonstrating a reverence for left-hand master James P. Johnson. On the classical side, his compositions suggest early Bartók with a Cole Porter twist. Say appears deceptively pensive on Naïve’s cover; the disc reveals a wily performer happily tossing paper on the piano’s strings for a rattling effect, or strumming the strings à la Cowell. Despite soaking up all these influences, Say hasn’t lost touch with his Turkish roots. Opening this collection, Black Earth summarizes Say’s lyrical style. Dampened strings suggest a tribal caravan rather than Cageian art-house pranks. Black Earth presents gestures and sounds we will hear in almost every other work here. Unveiling a longer, more episodic story, Concerto “Silk Road” adds chamber orchestra seasoned with Eastern spices. The two pieces for piano and orchestra splash Say’s riffs onto a bigger canvas. Eliahu Inbal and the Orchestre National de France accent all the right colors. With their lush, storybook gestures and modernist flair, the four short movements of Say’s Sonata for Violin and Piano wouldn’t be out of place on a cruise ship’s tea-time recital. When required, violinist Laurent Korcia slushily channels Franck and Debussy. I’d like to hear another pair’s take on this sonata. An encore taped live, the explosive Paganini Variations blends everybody’s favorite caprice with Tatum-inspired riffs and hotel-lobby swank. The pert closer, Dervish in Manhattan, hints at Say’s modern jazz inclinations, mixing and matching without being assertive. I imagine peripatetic explorer Yo-Yo Ma will collaborate with him someday. (Don’t adjust your set! Say’s first name isn’t misspelled. Unique to Turkish, the “ı” in Fazıl is an “i” without a dot and is pronounced “uh.”)

“Dialogues.” György KURTÁG: Pilinszky János: Gérard de Nerval (1984); Kroó György in memoriam (1997). Philippe SCHOELLER: Isis II (2001); Omaggio Kurtág (2001); Lamento (1996). Pierre BOULEZ: Dialogue de l’ombre double (1995). Pascal Gallois (bassoon), Garth Knox (viola), Sarah O’Brien (harp), Nicholas Isherwood (bar.). Stradivarius STR 33625 (http://www.stradivarius.it/). You probably didn’t realize it needed freshening up, but Pascal Gallois has redefined the contemporary bassoon. This is the fellow for whom Berio wrote his nearly impossible bassoon Sequenza XII (DG 457038), which requires almost constant double-breathing for the whole of its 18 1/2 minutes. “Dialogues,” Gallois’ Stradivarius recital, is stupendous. Rewritten from its clarinet beginnings, Boulez’s bassoon version of Dialogue de l’ombre double is the centerpiece. Dialogue sounds better on Gallois’ bassoon than Damien’s clarinet (DG 457605): Finally you can hear the difference between the live instrument and the electronics. Philippe Schoeller (b. 1957) was a new name for me. Three pieces demonstrate invention and assuredness. Gallois teams with Arditti Quartet violist Garth Knox in Lamento, an excellent duet emphasizing the viola and bassoon’s differences. I recently encountered Carter’s duet, Au Quai (Bridge 9128), and Schoeller’s 11-minute drama lends greater credibility to this combination. Versatile baritone Nicholas Isherwood appears in Omaggio Kurtág, a setting of Shakespeare’s Sonnet 113. Isis II matches harpist Sarah O’Brien with a bassoon that must move through the performance space. Two expertly crafted Kurtág miniatures, Pilinszky János: Gérard de Nerval and Kroó György in memoriam, bookend this astonishing recital.

“Music for Two Pianos.” Michael NYMAN: Taking a Line for a Second Walk (1986); Lady in the Red Hat (1985?); Water Dances (1985?). The Zoo Duet. Signum SIGCD506 (http://www.signumrecords.com/). Distributed in the US by Qualiton (http://www.qualiton.com/). A previous Nyman discussion qualifies me to discuss this as other than a detractor. I generally avoid discussing egregiously bad recordings but this one warrants a consumer alert. Ostensibly it presents three piano works in arrangements for two pianos. Rather than pianos, I hear rather crude synthesizers. The perpetrators are identified as the Zoo Duet, with no further information. Zoo is apt. Lady in the Red Hat originates from Nyman’s score for Greenaway’s A Zed and Two Naughts. Possibly we hear one pianist multi-tracked. I sincerely hope it’s not Nyman. The tinny sonorities are dreadful, pale comparisons of these pieces’ original instrumental versions, e.g., the two Water Dances on Michael Nyman Live (Virgin 7243 8 39917 2 3). Could it be that someone fed the digital sheet music to the synthesizer? Sleuthing on Nyman’s website turns up a similar human-initiated two-piano release with the same program, along with other coincidences, suggesting that this frightful assault might be a stealth reissue! The booklet repeats biographical information from Nyman’s website. The disc’s spine contains an embarrassing typo: “Music for To Pianos.” Nyman deserves better.

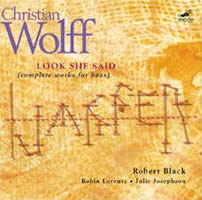

“for two pianists …and three.” Christian WOLFF: Duo for Pianists I (1957); Exercise 22 (Bread and Roses, for John) (1982); Duet I (1960); Exercise 21 (Oh Freedom) (1981); For Kristine and Mats (from Christian) (1994); Snowdrop (1970); three versions of Duo for Pianists II (1958); Variations (Extracts) on the Carmans Whistle Variations of Byrd (1972); two versions of Tilbury 2 (1969); Exercise 20 (Acres of Clams) (1980); Two Pianists (1993-94); Exercise 19 (Harmonic Tremors) (1980); Sonata for Three Pianos (1957); Braverman Music (1978); 70 (and more) for Alvin (2001); Fragment (2001). Mats Persson, Kristine Scholz, Christian Wolff (piano). content SAK 4610-8 (http://www.content-records.se/). Distributed by CDA (http://www.cda.se). Available at Swedish Music Shop (http://www.swedishmusicshop.com/). “Look She Said.” Christian WOLFF: Look She Said (1991); Jasper (1991); String Bass Exercise out of “Bandiera Rossa” (1975); Dark as a Dungeon (1977); Untitled (1966). Robert Black (bass), Robin Lorentz (violin), Julie Josephson (trombone). mode 109 (http://www.mode.com/). Content, a bright little Swedish label, released a two-CD set brimful of music for two and three pianists in time for Wolff’s 70th birthday. The composer himself visits with Mats Persson and Kristine Scholz, an earnestly capable duo whose previous recordings include a Feldman set (Alice ALCD 024). The well-written booklet offers this visionary Rzewski quote: “… Cage came close when he said … [Wolff’s music] was like the classical music of an unknown civilization.” Possibly the so-called New York School’s least glamorous member, Wolff crafts music that stammers like stubborn adults trying to learn a foreign language. Through clever interleaving of old and new works, graphic and traditionally notated, some requiring vocalizations and preparations, Persson and Scholz traverse Wolff’s varied spectrum. For example: Duo I, which tosses pitches into the wind where they scatter like breadcrumbs, is followed by Exercise 22’s marching rhythms, which in turn lead to the four-handed piano Duet I’s airy pointillism and infrequent inside-piano sounds. The 19:20 Snowdrop is a favorite. Traversing the same gentle material, the two pianos amble slightly out of phase, stuttering over short scale fragments that remind one of those old intercontinental telephone conversations in which each party’s words were delayed by a second or two. Persson and Scholz present Duo II and Tilbury 2 in multiple versions. Several works, such as the folksong-quoting Exercises, are first recordings. One particularly delicate work is reproduced on the booklet’s cover: For Kristine and Mats (from Christian), a clever arrangement of pitches found in the three names. Wolff joins in for the tiny, splintery Sonata for three pianos and a three-piano version of 70 (and more) for Alvin. Definitely seek this out to balance your collection of Cage and Feldman. Volume 4 of mode’s “Edition Christian Wolff” offers all five of the existing solo bass pieces played by Robert Black. The five-part Look She Said uses three folk songs: “All the Pretty Horses,” “The Grey Goose,” and “Cindy.” Black must also sing and whistle. The third movement showcases his virtuosity when perfectly tuned high double-stops mix with high-pitched “who”-ing and humming. For the four-section Jasper, Black is joined by violinist Robin Lorentz, who highlights Black’s impeccable intonation and solid bow control. The unlikely pairing of trombone (Julie Josephson) and bass appears in Dark as a Dungeon, an exploration of the Merle Travis tune. Black solos in the grand String Bass Exercise out of “Bandiera Rossa,” variations on an Italian revolutionary song mixed with Wolff’s own setting of Mao’s texts. The disc closes with the sonorous buzz of electric bass guitar in Untitled.

[More Grant Chu Covell, Rambles]

[Previous Article:

Two ECM Beauties: Holliger and Lachenmann]

[Next Article:

The Best Kind of Attitude: TACET]

|