Collections and Colecciónes

|

Grant Chu Covell [May 2002.]

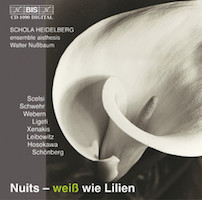

Nuits — weiß wie Lilien: Works by Toshio HOSOKAWA, Giacinto SCELSI, Arnold SCHOENBERG, René LEIBOWITZ, Anton WEBERN, Cornelius SCHWEHR, Iannis XENAKIS, György LIGETI. Schola Heidelberg, Ensemble Aisthesis, Walther Nußbaum (cond.). BIS CD 1090 (http://www.bis.se/). Distributed in the US by Qualiton (http://www.qualiton.com/). Contemporary choral music is a tough genre to explore. The all-Xenakis program with the New London Chamber Choir, Critical Band, and James Wood conducting (Hyperion CDA 66990) and the all-Cage program, Litany for the Whale, with Theatre of Voices, Paul Hillier, and Terry Riley (Harmonia Mundi HMU 907187) are both great discs, but probably excessive for most. Some collections are downright intimidating, such as the excellent ten-CD Schola Cantorum set (Bayer CAD 800 901). This Schola Heidelberg recital is an excellent view of modern and contemporary choral music. The recording quality is crystalline, all the voices are well matched, and the variety of works on the disc — some with instruments, some for chorus alone — makes for a wonderful program. It was recorded in a resonant space and the chorus has just the right amount of vibrato for an expressive sound. The curtain-raiser shows off the chorus to great advantage. Toshio Hosokawa’s Ave Maria starts with inchoate syllables before landing on rich chords of the sung Latin text. There’s also a tape part of breathing noises, but the focus of this work is the delicacy the chorus brings at all dynamic ranges and registers. The first of two complementary works by Giacinto Scelsi follows. Tre canti sacri is as traditional as Scelsi ever got. Each movement hovers around a gently moving unison line, and parts of the chorus drift away and back with microtones and glissandi. The effects are actually very subtle, considering that this is Scelsi. The three movements are Angelus, Requiem, and Gloria, and Scelsi handles the texts rather loosely and unconventionally. Another recording (Solstice FYCD 119) with the Groupe Vocal de France stresses the undeniable mysticism in this work, but the Schola Heidelberg, more formal and rigorous, reveals how unsettling this music can be. Later on come the three angular movements of TKRDG for six male voices, three percussionists, and amplified guitar. The purely syllabic text makes no sense, and the whole work emanates a jarring primal air. This is more representative Scelsi — the predominant unpitched drum and jangly metal texture of the percussion alongside amplified guitar suggesting an indigenous ensemble. And the intentionally harsh male voices contribute to the ethnographic quality. As a practical joke, I’d love to play this for an ethnomusicologist for analysis. Schoenberg’s De profundis (Psalm 130), Op. 50b, is sandwiched between the two Scelsi works (Schoenberg would bristle at the association!). De profundis is an odd little a cappella work. Suddenly we are in the world of serialism, and you can hear how the chorus gives strict intonation a higher priority than the slithery expression of the Scelsi and Hosokawa that precedes. To my ear, the Schola Heidelberg emphasizes the awkwardness of Schoenberg’s choral writing. Later in the disc is another serial work, Two Settings, Op. 71, by René Leibowitz, based on poems of William Blake. Leibowitz achieves a lush texture built from several notes at a time, whereas Schoenberg takes several groups of notes and makes them grittier. Spoken phrases in the Schoenberg also contribute to its comparative roughness. The Schola Heidelberg is so very adept at effectively characterizing these short works. Two sets of Webern songs appear: Drei Lieder, Op. 18, for soprano, E-flat clarinet and guitar, and Zwei Lieder, Op. 19, for mixed chorus, celeste, guitar, violin, clarinet and bass clarinet. Nußbaum encourages a musical and balanced interpretation — especially compared with Boulez’s recent approach (DG 437 786-2), which has members of the Ensemble InterContemporain competing rather than playing together. Op. 18 is superbly spiky Webern. The E-flat clarinet is a shrill instrument (shriller than the B-flat or A clarinets which are staples in most orchestra repertoire) and the guitar is folksy. They’re short, teasing works, and much easier to appreciate in a varied program where their terse nature is refreshing. Cornelius Schwehr’s Deutsche tänze for just five female voices uses a short parable by Bertold Brecht. Pops, wheezes, and whispers tell the absurd and frightening story of a man’s execution. With this disc in hand, I was surprised to discover that I have four recordings of Xenakis’ Nuits. It’s an early work (1967-68) and is dedicated to the plight of political prisoners everywhere. Xenakis himself had been living in exile in France because of his student activities in Greece. Adès 14.112-2 is a four-disc set, Music de Nôtre Temps: Repères 1945-1975, and Nuits is performed by soloists from the ORTF chorus with too much vibrato and very little attempt at blending the ensemble. But this documents perhaps only the second ensemble to perform the work; in 1968 Xenakis’ technical demands on choristers were fresh and different. The Groupe Vocal de France recorded a somewhat undistinguished Nuits in 1984 (Arion ARN 68084). The more traditional Messiaen works on the same disc, Cinq Rechants and O Sacrum Convivium, are a better match for the group. The Hyperion disc mentioned earlier, with the New London Chamber Choir, was taped in 1997 and represents a mature and experienced handling of Xenakis and this type of choral writing. They behave much like a crowd here, and the roughness and vigor are appealing. Finally, Schola Heidelberg’s traversal (2000) is the most recent, and they seem the least shaken by Xenakis’ squeals, nasal twangs, blips, and outbursts. It’s also the fastest at 8:33. The ORTF takes 11:22, Groupe Vocal de France 10:40, and New London 8:53. Ligeti’s Lux Aeterna demands that the chorus act as a single instrument. Each voice is as important as the others, and together they create a penetrating texture. Schola Heidelberg is surprisingly delicate in this performance, compared to the edginess of the Xenakis or Scelsi works, and consequently this Ligeti is infused with a fragile and temporal quality. Each voice’s entry is very gentle and subtle, even the high sopranos. At 8:35, this reading is much faster than the Schola Cantorum’s 9:45 (in the big brick on Bayer), which makes a huge difference. The Schola Cantorum is languid by comparison, and I much prefer the frailty and sheer texture of the Schola Heidelberg. Interestingly, the faster speed is easily absorbed when the voices’ attacks are smooth. This is a remarkable recording of great clarity and musical depth, programmed with fine sensitivity and variety. Anyone with the vaguest interest in testing these waters should get it. I imagine that Nußbaum and the Schola Heidelberg have a vast repertoire, and that this is just an intelligently collected sampling. I look forward to their next release, perhaps something with more instruments or orchestra. (You know I want to hear them perform Nono and Lachenmann.) The Carnegie Hall Millennium Piano Book: Works by Louis ANDRIESSEN, Milton BABBITT, Elliott CARTER, Chen YI, HANNIBAL, John HARBISON, Wolfgang RIHM, Frederic RZEWSKI, Tan DUN, Ellen Taaffe ZWILICH. Full-length CD with book features Ursula Oppens (piano). Boosey & Hawkes ISMN M-051-24617-5. In March 2000, Ursula Oppens and four young pianists premiered The Carnegie Hall Millennium Piano Book, a collection of ten piano works by contemporary composers. Boosey & Hawkes published the score for all ten pieces along with a CD of Ursula Oppens playing them. This is probably easier to find in a sheet-music store than in a CD shop. I got mine from a huge stack at Patelson’s Music House in New York City, across the street from Carnegie Hall. The idea behind this collection is that young pianists at “ intermediate through professional level ” can learn ten contemporary works of great variety and varying difficulty. The pieces form a fairly complete picture of what’s being written for piano these days. A few require some extended techniques (inside the piano, on the piano cover, under the keyboard, etc.), and how else could Andriessen bump into Babbitt, or Tan Dun follow Carter? (Personally, I might have added Ferneyhough, Finnissy, or Nyman.) It’s the inclusion of definitive performances by Ursula Oppens that makes this a must-have item for any aspiring 21st-century pianist (the Andriessen is doable at a slow tempo ) or weekend theorist (you could puzzle out the Babbitt or the Carter). You might never play any of these as well as she does, but there’s so much to be learned by following along! The CD adopts the non-alphabetic order of the printed items. In each of Carter’s Two Diversions, the pianist’s hands must conspire to propel and keep distinct multiple lines of different character. Rzewski’s The Days Fly By is all over the place, including on the piano cover and under the keyboard. On an Unwritten Letter (Harbison) is contemplative with hymn-like moments of repose, and Yi’s Ba Ban explores the keyboard’s extremes, drawing upon non-Western influences. Rihm’s 6 Zwiesprache (Dialogue) are the shortest and apparently simplest works, each an in memoriam for a departed friend. A Gustave Moreau woodcut inspires Andriessen’s Image de Moreau, which blends the composer’s distinctive minimalist style with the impressionistic figurations of Debussy and Ravel. Predictably, Babbitt’s The Old Order Changeth is the most difficult of the set; precise rhythms and dynamics appear on widely spaced notes over an endless number of pages, but it’s also a bit jazzy — that would be the trick to learning it. Tan Dun’s Dew-Fall-Drops seems the easiest, with its mainly inside-the-piano strumming and plucking, but it takes control and patience to do it just right. Lament (Zwilich) is another in memoriam work, while Hannibal’s John Brown and Blue is more extroverted, part history, part parable. Nuevo. Kronos Quartet (David Harrington, John Sherba, violins; Hank Dutt, viola; Jennifer Culp, cello), et al. Nonesuch 79649-2 (http://www.nonesuch.com/). This new CD from Kronos (with Jennifer Culp replacing Joan Jeanrenaud) is an essential postcard from Mexico. I found that it cut straight to the mystical and magical qualities of the people and culture. Minimal program notes mean that you’ll be listening instead of reading, even though the thick booklet is an attractive one with many great pictures. In the passing parade of this disc’s 14 tracks, the quartet is supported by all kinds of percussion, taped sounds of Mexican music and street noise, and other stuff I can’t begin to describe. The variety on this disc, along with some excellent engineering (magic and artistry done in the studio and in the final mix), encourages close listening. Nuevo is the Kronos’ best release in a long time, and this from a diehard Arditti fan. A highlight for me is Juan García Esquivel’s Mini Skirt, in an arrangement by Osvaldo Golijov (he’s credited with arranging seven tracks, and Kronos recorded his The Dreams and Prayers of Isaac the Blind). I was not disappointed: Kronos “plus friends” gives a smart and sassy version of Esquivel’s campy pop tune. And just as Esquivel often did, we get to hear some sound effects and music bouncing between the speakers. Another must-hear is the recasting of Silvestre Revueltas’ Sensemayá. Revueltas is the one they call the Mexican Charles Ives, but he was more intensely brilliant, his life tragically destroyed by alcohol. Sensemayá is about a Cuban ritual killing of a snake, and four additional percussionists carry it aloft. The reduction of Revueltas’ cataclysmic orchestration is surprisingly spare and restrained when done by just four strings. It does work this way — the emphasis is more on the tunes than on the orchestra buildup — though I had to play it several times to get used to it. I’m certain listeners who go from this to the original for full orchestra will be blown out of their socks. The opener is Severiano Briseño’s El Sinaloense. In Golijov’s arrangement, the quartet is made to compete with an intentionally scratchy and overamplified image of itself (electronic strings appear throughout). It may sound unpleasant, but it reminds me exactly of the coarse yet catchy tunes you’d hear pounding out of a cheap transistor radio in a Mexican market. This is one of the tracks to trail off into street sounds, a wonderful effect setting the mood and locale for all that follows. I won’t do a laundry list, but several striking tracks deserve mention. Cuatro Milpas has unexpected mood changes and incorporates a street organ; it leads into the next, Chavosuite, an odd self-contained mélange of several numbers (one of them Beethoven), complete with sound effects — music familiar to many Mexicans from popular television shows. In 12/12, Kronos is paired with Café Tacuba, a small band of instruments and electronics, to create the strangest and most innovative selection here. (The press release labels Café Tacuba a “Rock en Español supergroup,” and I’m not enlightened enough to know what that really means.) Five disjunct sections blend pre-recorded sounds (one of the many neat juxtapositions is snips of the original orchestral Revueltas over traffic noise) with the live instruments. The title refers to December 12th, the Day of Our Lady of Guadeloupe, a day of celebration all across Mexico. El Sinaloense is reprised at the very end, in a Dance Mix version by DJ Plankton Man, completing this satisfying round trip. Thomas QUASTHOFF: Evening Star. Orchester der Deutschen Oper Berlin, Christian Thielemann (cond.). DG 289 471 493-2 (http://www.universalclassics.com/). What an amazing voice this man has! I spend most of my time in the relatively less beauteous land of the contemporary, but I know a great voice when I hear it. Quasthoff has one of the most laudable instruments of our time, which he uses with enormous sensitivity — the sort of voice that brings home why music can be so powerful. Evening Star has arias by Wagner, Strauss, Weber and Lortzing, and until now I have never had a reason to listen intently to Albert Lortzing (here are excerpts from Zar und Zimmermann and Der Wildschütz). Quasthoff’s characterizations and consummate artistry make listening a true pleasure. The accompanying Chor und Orchester der Deutschen Oper Berlin, under Christian Thielemann, rises to the occasion. So does Christiane Oelze, in one of the Lortzing arias. Interest in Quasthoff spurred me to revisit his recording from a year or so back of Mahler’s Des Knaben Wunderhorn (DG 289 459 646-2) with Anne Sofie von Otter and the Berliner Philharmoniker under Claudio Abbado. If your perspective on Mahler has focused on the symphonies, it will be surprising, perhaps a bit surreal to hear the original versions of songs and movements that made their way into those works. Here too, as in Evening Star, Quasthoff’s diction and expression are unmatched, and conductor and orchestra sound invigorated. David FELDER: In Between, Coleccion Nocturna. Morton FELDMAN: The Viola in My Life IV, Instruments II. June in Buffalo Festival Orchestra, Harvey Sollberger, Jan Williams (conds.), Daniel Druckman (percussion), Jean Kopperud (clarinets), Jesse Levine (viola), James Winn (piano). EMF CD 033 (http://www.cdemusic.org/). David FELDER: Six Poems from Neruda’s “Alturas ”, Coleccion Nocturna, a pressure triggering dreams. June in Buffalo Orchestra, Magnus Martensson, Harvey Sollberger (conds.), David Felder (electronics), Jean Kopperud (clarinets), James Winn (piano). Mode 89 (http://www.mode.com/). David FELDER: Journal, Canzone XXXI, November Sky, Third Face, Three Lines from Twenty Poems. June in Buffalo Chamber Orchestra, Harvey Sollberger, Bradley Lubman (conds.), Rachel Rudich (flute), American Brass Quintet, Arditti String Quartet. Bridge BCD 9049 (http://www.bridgerecords.com/). I think I’ve said this before: Morton Feldman’s The Viola in My Life has got to be one of the all-time best titles for an opus. I was happy to get the EMF disc; it ably rounds out the first three parts of The Viola in My Life (CRI 620). Parts I, II and III are scored for intimate-sized ensembles, whereas Part IV is for viola and orchestra. Jan Williams, who conducts part IV, appears on the CRI as percussionist in Feldman’s Why Patterns? As in the other three parts, the viola is omnipresent, gentle, and searching. Single notes, sometimes chords, surface and disappear in the mostly quiet orchestra; only the violist seems to get a melody. It emerges plaintively, almost trying to soar above an imaginary weight (perhaps the orchestra) that constrains it. Sometimes the orchestra seems stuck on a repetitive pattern or phrase — a recurring birdcall or a downward-moving octave — but the viola with its unbreakable melodic thread gives this static piece direction. Few works impart a timpani tremolo such pungency or instill the violist’s rare grace note with such emotion. This is approachable Feldman: a comfortable length with easy-to-follow musical material. This EMF was my introduction to David Felder, and I had to hear more. Felder has deservedly won his share of acclaim and awards, and in 1985 Feldman handpicked him to be his peer at the University of New York at Buffalo. If you like composers who know what to do with poetry, or who can successfully integrate electronics into their work, or who just plain know how to write music that’s worth hearing, then you must get to know Mr Felder You can also hear his work on a recent disc from Mode, and an older one on Bridge. Interestingly, all these have similar cover art (especially the EMF and Mode releases), done by the same artist, Alfred DeCredico. The EMF begins with Felder’s In Between for solo percussionist and orchestra, an engrossing work. He crafts dissonant, glacial blocks of orchestral sound and the solo percussionist wanders through them. The opening (staggered entrances and exits over long-sustained chords) is a touch otherworldly, and it’s hard to tell when the soloist comes to the fore, as the orchestra has three percussionists of its own. Felder’s orchestration is skillful: A drawn-out oboe phrase supported with bassoons can be punctuated by slow-moving muted strings. There are building climaxes that emphasize held notes, and even octaves or occasional small-interval brass glissandi I have heard in Scelsi. I don’t feel right calling this a concerto — both soloist and orchestra seem to be on the same team, if that makes sense. Coleccion Nocturna, Felder’s other item on the disc, is 15 years younger than In Between. It’s more clearly a concerto, in this case for solo clarinet, piano, and orchestra. Interestingly, the clarinet is much more ostentatious than the piano, whose largely linear and upper-range rôle is to intercede between clarinet and orchestra. An atmosphere of virtuosity has the clarinet competing with the orchestra for attention and dominance. I found it much less commanding than In Between until about the two-thirds point, when the pulse of the work slowed down greatly as if revealing a mystery. Now, I didn’t find any mention of it in the notes, but I heard what could only be a tape. A few times I caught the distinct backwards attack and release of a piano note, but there were moments when I could briefly hear the piano note beating, as if playing against a slightly slowed-down double of itself. This made me listen more closely; not that it’s a parlor trick, but it was clear that there is a lot more going on in this piece than I first imagined. Felder has a splendid grasp of what I like to think of as “pulse.” This isn’t a foursquare boom-box rhythm coming from a passing car; it remains in the background as the basic speed at which major changes occur. Felder handles slow and relaxed pulses amazingly and, come to think of it, so did Feldman in his later oeuvre. Felder, though, has more propulsion and even intensity at slow pulse then Feldman did. Mode 89 presents the chamber version of Felder’s Coleccion Nocturna, scored for clarinet, piano and tape (the notes do say that the orchestral version has a tape part!). It’s fascinating to hear these siblings side by side. Not everybody’s idea of fun, but viewing a composer work through similar material in two coherent and substantial versions lends great insight into the choices a composer makes, especially when each alternative produces such a convincing statement on its own. While it’s not as easy to hear that clarinet and piano proceeding in variations, the result becomes richer and more introspective as new sounds are explored. The Mode recording starts with a virtuosic orchestral work, Six Poems from Neruda’s “Alturas ” Three differently sized and exquisitely crafted movements wrestle with Neruda’s poetry. The first is a loud miniature of barely three minutes, with a searingly fast melodic line whose great leaps are propelled throughout the orchestra. The central one is the longest (over 14 minutes), and it combines four poems — the outer movements tackle one poem each. The finale reflects the repetitive rhythms in the text with moments of driving repetition. The diversity of length, texture and mood creates an arresting spell. The last effort, a pressure triggering dreams, is for large orchestra and electronics. The electronics appear in multiple guises: benignly as amplification for selected instruments, and strikingly as sampled sounds manipulated from a keyboard. The synthesizer employs mostly flute-sampled tones, and after an opening with an extended orchestral outburst, the texture turns thin and eerie as the synthesizer comes to the fore — gentle, clicking, insectile noises and a wash of distorted flutes. In 1995 Bridge released a disc with five Felder titles (BCD 9049). These show that he has been an assured composer for quite some time. This CD also underscores some preoccupations that appear in the more recent works. Journal, for orchestra, starts with an active, even calisthenic line similar to Six Poems. Journal’s opening keeps to a handful of wide and dissonant intervals, and, like both versions of Coleccion Nocturna, there’s a point where the pulse relaxes and the outward-looking music changes character. A short brass quintet, Canzone XXXI, is neatly scored so that it sounds like more than five players, and the Arditti Quartet plays Third Face, which juxtaposes jumpy and angular melodic lines built from similar intervals against long, slow contours. November Sky, for flutes and computer-processed sounds, finds treasure in the classic (perhaps even cliché) combination of electronic and synthesized flute, but then the electronic palette begins to open like a wedge. The disc ends with another orchestral work inspired by words, Three Lines from Twenty Poems. After Mozart: Works by Alexander RASKATOV, W.A. MOZART, Valentin SILVESTROV, Alfred SCHNITTKE, Leopold MOZART. Gidon Kremer, Kremerata Baltica. Nonesuch 79633-2 (http://www.nonesuch.com/). This is a thought-provoking CD: six titles by five composers — three Russians influenced by Mozart, Mozart’s father, and Mozart himself. But because the three contemporary items take Mozart’s music and his very existence as their starting point, the disc is just as much about listening to Mozart as it is a collection of attractive music. We have no way of knowing what Mozart’s music sounded like in his day, despite the best intentions of historically informed performances. We cannot hear Mozart’s music as his contemporaries heard it because we have been influenced by so many things musical and nonmusical which were not part of Mozart’s time. A performance of Mozart’s Clarinet Quintet should never make anyone think of Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring, but no composer or performer active in our time has not somehow been affected or informed by Stravinsky. Some of today’s most gifted composers and performers create art that wrestles with these issues — how the music of one age can alter our perceptions of that from another. Gidon Kremer’s take on the Mozart and the three contemporary works falls into this category. The disc opens with the first of the contemporary works, Five Minutes from the Life of W.A.M. by Alexander Raskatov. This five-minute excursion is a gently atmospheric opener for solo violin, string orchestra, and percussion. It plies a dreamy ambience, suggesting mundane events in Mozart’s life. We hear fragments suggestive of Mozart, and it’s easy to imagine that these are Mozart’s own doodlings, or perhaps even the misrememberings of other music Mozart might have heard around him (though Mozart apparently had a perfect musical memory). Valentin Silvestrov’s The Messenger is another Mozart-inspired work. Written to honor his late wife, the violin / piano layout is framed by taped wind sounds. It’s very quiet, almost inaudible, and given its circumstances, it’s easy to imagine this as music from the beyond — or as fragments of a Mozartian violin sonata heard from afar. Silvestrov is a most appealing composer, and in other works (his melancholy Fifth Symphony) he draws upon the past in all sorts of contextual and self-referential ways while clearly being part of the 20th century. Kremer teamed up with Tatiana Grindenko to record Alfred Schnittke’s Moz-Art à la Haydn on DG 429 413-2. This new outing is more assured, though I’m not so wild about having another recording by the same team. Where the Raskatov and Silvestrov seemed to send us back into Mozart’s day, this pulls Mozart and Haydn into our modern ethos. Schnittke’s contribution is jarring and far removed from the contemplative atmosphere of the other two contemporary efforts. The first Mozart opus is a standard, Serenata Notturna, K. 239. Kremer and another solo violinist, Eva Bindere, bring a boisterous and assertive vibe to this three-movement work for solo strings with timpani. While Raskatov and Silvestrov try to blend themselves into Mozart’s world, this serenade bluntly asserts that there is an abyss between Mozart’s world and our own. During the cadenzas in the last movement, the soloists drift into the 20th century with snatches of the Berg Violin Concerto and other non-Mozartian gestures. This will probably offend purists, but I find it very refreshing to be reminded that we’re not in Mozart’s day (I also appreciate someone like Robert Levin, who improvises a cadenza to a Mozart piano concerto and tries to stay within Mozart’s idiom). Kremer has essayed a modern cadenza before: A favorite recording of the Beethoven Violin Concerto used Schnittke’s cadenzas, and it too quoted the Berg Concerto and most every major violin concerto since Beethoven. I’m sure the audiences of Beethoven’s day found the cadenzas he wrote for Mozart’s piano concertos similarly unsettling. One of Mozart’s most popular works (and one of the most overplayed and overdone classical chestnuts of all time) also gets the Kremer treatment. Eine Kleine Nachtmusik must have been programmed with a sense of irony. Why is this warhorse here? For Mozart, Eine Kleine was a five-movement work. Today we hear only four — a minuet with trio has been lost to us. This is a very good performance (well, it kept my attention). I generally lunge to snap off the radio whenever it comes over the airwaves. I hope record clerks recommend this disc when folks wander in innocently asking for Eine Kleine. Leopold Mozart’s Berchtolsgadener is the last item. Known as the “Toy Symphony” or “Children’s Symphony,” the elegant elder Mozart’s music is enhanced by modern sound effects, including toys and bird sounds. There is even a toy cell phone ringing, answered by a transistorized “Hallo?”

Andriessen, Babbitt, Carter, Chen Yi, Felder, Feldman, Hannibal, Harbison, Hosokawa, L Mozart, Leibowitz, Ligeti, Mozart, Raskatov, Rihm, Rzewski, Scelsi, Schnittke, Schoenberg, Schwehr, Silvestrov, Tan Dun, Webern, Xenakis, Zwilich

[More Grant Chu Covell]

[More

Andriessen, Babbitt, Carter, Chen Yi, Felder, Feldman, Hannibal, Harbison, Hosokawa, L Mozart, Leibowitz, Ligeti, Mozart, Raskatov, Rihm, Rzewski, Scelsi, Schnittke, Schoenberg, Schwehr, Silvestrov, Tan Dun, Webern, Xenakis, Zwilich]

[Previous Article:

Brno's Exposition of New Music]

[Next Article:

A Personalized Ramble]

|