“Come io passo l’estate”: Italian Vacation 3.

|

Grant Chu Covell [December 2005.]

Niccolò CASTIGLIONI: Cangianti (1959); Tre Pezzi (1978); Come io passo l’estate (1983); Dulce Refrigerium (Sechs Geistliche Lieder) (1984); Sonatina (1984); HE (1990). Sarah Nicolls (piano). Metier MSV CD92089 (http://www.metierrecords.co.uk/). A crisp division separates Castiglioni’s silvery Cangianti (Changes) from his other piano works. The 11-minute fingerbuster parallels other contemporaneous mid-century work, except that Castiglioni was more given to cantabile gestures than his Darmstadt pals. The later works, looking askance at tradition, tend towards parody. Spans of Tre Pezzi take swipes at Messiaen’s bird-calls and Webern’s concision. Come io passo l’estate (How I spend the summer) strings ten Satie-like trifles portraying favorite vacation spots in the Dolomites. Gentle tunes are harmonized oddly; uneven phrases linger unexpectedly. Chopin, Schumann and Debussy infiltrate the set. Castiglioni was one of the few contemporary composers to acknowledge the animal magnetism of tonal chords. The first piece, “Arrivo a Tires,” could score any of M. Hulot’s holidays. One piece, “Antonio Ballista dorme in casa dei Carabinieri” (Antonio Ballista sleeps at the police station), caricatures the snoring pianist who premiered the work. Dulce Refrigerium (Sechs Geistliche Lieder)’s title invites misunderstanding. Dulce Refrigerium translates as “Chilled Sweetness,” while Geistliche can improperly suggest “ghostly.” These “religious songs” channel Satie’s ghost by way of meandering gentility and tonal associations. Beethoven’s Les Adieux horn-call dribbles throughout, culminating in a diminutive 17-second, eight-dyad finale. Similarly, the nose-tweaking Sonatina skitters from one 20th-century location to another. Koechlin’s charming but aimless piano works come to mind. The central “Laendler” surprises with an assertive single voice and broken-record repetitions. The final chord appeared in Come io passo l’estate. “Fughetta” applies the venerable technique to a Bartókian shard. A Les Adieux gesture closes the work. Like a castoff, the four-minute HE reminds us that Castiglioni had an ear for minimalism despite his serial upbringing. His interpretation cursory compared with Nicolls’ insights, Thomas Adès presented Come io passo l’estate on a recital disc (EMI 7243 5 57051 2 9). Nicolls provides the necessary elegance to Cangianti with the perfect touch of irony. This Metier production captures every nuance. Castiglioni deserves champions, and Nicolls moves to the head of the pack. As Nono and Berio are also in her repertoire, she’ll be back on these pages sometime soon.

Pierluigi BILLONE: ME A AN (1994); ITI KE MI (1995). Frank Wörner (bar.), ensemble recherche; Barbara Maurer (viola). Stradivarius STR 33716 (http://www.stradivarius.it/). Distibuted in the US by Allegro Music (http://www.allegro-music.com/). Billone stands at the vanguard of composers who studied under Lachenmann and Sciarrino. If you believe that contemporary music must by definition forge ahead into new territories and fresh sounds, then Billone is your man. ME A AN (Measure. Two Heavens.) is scored for low male voice, two bass clarinets (sometimes doubling on standard clarinets), percussion, viola, cello and contrabass. There is no text. Wörner hums at the music’s start. We also hear whistling, the instruments generally appearing en masse. The clarinet duo emphasizes multiphonics, metallic rasping; bowed gongs dominate the percussion, and the low string trio concentrates on nether textures, ghostly glissandi and brittle harmonics. The ensemble’s sound is close to electronic. The Babylonic title intends to confuse. In contemplating the ruins of previous civilizations, Billone attempts to discover new sounds. Even the experienced listener will hard put to discover familiar gestures. For its 35 minutes, the music snarls like a malevolent beast. The 29-minute ITI KE MI (New Moon. Mouth. Feminine.) features a solo viola radically restrung and tuned. The multi-colored score calls for a daunting array of expression and technique. Billone leapfrogs over commonplace mistuned-viola croaks, only to plunge into a toxic sea of convulsive gasps. One hears Maurer performing on a broken machine, the question becoming: Can the poor, belabored instrument be returned to normality? The newcomer may wonder whether all new music need be so alienating. The answer of course is no, but this stimulating landscape requires exploration. Ensemble recherche’s premiere of Billone’s string trio Mani. Giacometti (2000) is in the Donaueschinger Musiktage 2000 brick (col legno WWE 4CD 20201); Mani. Long (2001) is on Durian 019-2.

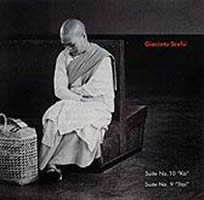

“The Scelsi Edition, Volume 4: The Piano Works 2.” Giacinto SCELSI: Suite No. 2, “The Twelve Minor Prophets” (1930); Action Music (1955). Stephen Clarke (piano). mode 143 (http://www.mode.com/). Giacinto SCELSI: Quattro Illustrazioni (1953); Suite No. 8, “Bot-Ba” (1952); Cinque Incantesimi (1953). Markus Hinterhäuser (piano). col legno WWE 1CD 20068 (http://www.col-legno.de/). Distributed in the US by Qualiton (http://www.qualiton.com/). Giacinto SCELSI: Suite No. 10, “Ka” (1954); Suite No. 9, “Ttai” (1953). Markus Hinterhäuser (piano). col legno WWE 1CD 31889 (http://www.col-legno.de/). Distributed in the US by Qualiton (http://www.qualiton.com/). Increased familiarity with Scelsi underscores his piano works’ strangeness. How could a composer who built entire movements from the slightest microtonal shifts write for the piano’s 88 fixed pitches? Whether you consider Scelsi’s keyboard compositions skillfully completed transcriptions or notated improvisations, many pianists find the Italian loner’s music attractive. Mode has released Suite No. 2’s first recording. Written when the composer was 25, this work bonds Scriabinesque flourishes with dance-hall propulsion. The 12 varying movements foreshadow the composer’s alternating frenzied and plaintive tendencies, but with Rachmaninovian usages. In the 1940s, Scelsi suffered a mental breakdown and cured himself by continually playing single notes on a piano and focusing intently upon each decay. Action Music comes from the end of Scelsi’s creative days. Sounding like Antheil or Ornstein, the nine movements employ crashing clusters and vigorous chord splashes. Clarke digs in resolutely, emphasizing the pages’ mighty contrasts. Quattro Illustrazioni whose four movements represent different incarnations of Vishnu has become rather well-recorded (see here). Hinterhäuser fluidly attacks runs to dramatize the movements’ extremes. At 28:49, Suite No. 8, “Bot-Ba,” isn’t the longest of his three considered here (No. 9, “Ttai,” is 38:08 and No. 10, “Ka,” is 22:18), but it’s definitely the most rambling in its Tibetan way. The flamboyant Cinque Incantesimi do really sound like transcribed improvisations. While the suites require architectural awareness, these lightning flashes make their own demands. Hinterhäuser’s release of the contrasting Suites 9 and 10 were taped in ’96, but has just been (re)released here in the US. “Ttai” attempts to express time, though Scelsi admonishes: “This suite should be listened to and played with the greatest interior calm. Restless people should keep away.” (This disqualifies me.) The narrow pitch focus suggests eavesdropping on a ruminating piano tuner. “Ka” primarily signifies “essence,” incorporating a restlessness that hints at violence absent from Suite 9. Hinterhäuser’s approach is more leisurely than other pianists. Bessette’s 2000 “Ttai” (mode 92; see here) occupies 36:20 while Bärtschi’s 1989/91 recording (Accord 200802) is significantly more rushed at 31:26 (Suite 8 on the same disc concludes at 24:38). As the field crowds, Hinterhäuser’s calmer approach grows enduring.

[More Grant Chu Covell, Italian Vacation]

[Previous Article:

Marco Polo’s do-it-yourself Hymnen]

[Next Article:

Loony for Tunes]

|