Mostly Symphonies 15.

|

Grant Chu Covell [October 2010.]

Felix MENDELSSOHN: Mitten wir im Leben sind, Op. 23, No. 3 (1830). Johannes BRAHMS: Begräbnisgesang, Op. 13 (1858); Schicksalslied, Op. 54 (1871); Symphony No. 1, Op. 68 (1876). Orchestre Révolutionnaire et Romantique, The Monteverdi Choir, John Eliot Gardiner (cond.). Soli Deo Gloria SDG 702 (http://www.solideogloria.co.uk/). Distributed in the US by Naxos (http://www.naxos.com/). Franz SCHUBERT: Gesang der Geister über den Wassern, D. 714 (1821); Gruppe aus dem Tartarus, D. 583 (1817; arr. J. Brahms 1871); An Schwager Kronos, D. 369 (1816; arr. J. Brahms 1871). Johannes BRAHMS: Alto Rhapsody, Op. 53 (1869); Symphony No. 2, Op. 73 (1877). Nathalie Stutzmann (c-alto), Orchestre Révolutionnaire et Romantique, The Monteverdi Choir, John Eliot Gardiner (cond.). Soli Deo Gloria SDG 703 (http://www.solideogloria.co.uk/). Distributed in the US by Naxos (http://www.naxos.com/). Johannes BRAHMS: Ich schwing mein Horn ins Jammertal, Op. 41, No. 1 (1861-62); Es tönt ein voller Harfenklang, Op. 17, No. 1 (1859-60); Nachtwache I, Op. 104, No. 1 (1888); Einförmig ist der Liebe Gram, Op. 113, No. 13 (1860-3); Gesang der Parzen, Op. 89 (1882); Symphony No. 3, Op. 90 (1883); Nänie, Op. 82 (1880-81). Orchestre Révolutionnaire et Romantique, The Monteverdi Choir, John Eliot Gardiner (cond.). Soli Deo Gloria SDG 704 (http://www.solideogloria.co.uk/). Distributed in the US by Naxos (http://www.naxos.com/). Ludwig van BEETHOVEN: Coriolan Overture, Op. 62 (1807). Giovanni GABRIELI: Sanctus and Benedictus a 12 (ca. 1615). Heinrich SCHÜTZ: Saul, Saul, was verfolgst du mich? (ca. 1650). Johann Sebastian BACH: Meine Augen sehen stets zu dem Herrn and Meine Tage in den Leiden from Nach dir, Herr, verlanget mich, BWV 150 (ca. 1704-7). Johannes BRAHMS: Geistliches Lied, Op. 30 (1865; arr. John Eliot GARDINER, 2008); Fest- und Gedenksprüche, Op. 109 (1889); Symphony No. 4, Op. 98 (1885). Orchestre Révolutionnaire et Romantique, The Monteverdi Choir, John Eliot Gardiner (cond.). Soli Deo Gloria SDG 705 (http://www.solideogloria.co.uk/). Distributed in the US by Naxos (http://www.naxos.com/). As Gardiner tells it, Brahms was not the progressive Schoenberg thought he was. The series’ nicely designed booklets do not offer program notes. Instead, Gardiner joins composer Hugh Wood in stoked conversation (NMC D070 offers Wood’s assertive 1982 Symphony). Gardiner’s opening words on the First: “Brahms’ sense of history was probably more pronounced than that of any other 19th-century composer.” When discussing the Fourth Wood reminds: “Of his labor on the First Symphony, Brahms said: ‘You haven’t the faintest idea what it feels like for us lot always to hear such a giant [Beethoven] marching along behind one.’” Gardiner establishes Brahms as the last of his line. The composer/pianist/scholar/editor loved the music of Beethoven, Mendelssohn, Schubert, et al. Brahms’ innovations are subtle, best visible to scholars who appreciate how he leveraged past structures and harmonies. Recall that Brahms labored on his First for more than 20 years, and that other orchestral ventures were less fraught. Purely as a concept, the symphony was something of an albatross. Schumann’s praise may have ignited unachievable expectations. (Robert’s gradual demise and whatever feelings Brahms had for Clara perhaps discouraged risk-taking.) Let us not forget that the First was premiered a few months after Wagner’s complete Ring, the “music of the future.” Conductor Hans Richter (champion of both Wagner and Brahms) labeled it “Beethoven’s Tenth” for good reason. With the exception of an all-Brahms Third program, Gardiner prefaces each symphony with works by Brahms and others. A fifth disc with the German Requiem will complete the series. Each pre-show establishes Brahms as a choral composer, and even when orchestra appears, voices take precedence. Begräbnisgesang shifts from dark to light with a few wondrous cadences thrown in. Schicksalslied’s thumping timpani anticipate the First’s weighty introduction. Gardiner reminds that Schubert and Brahms are distant cousins. As with disc-filler elsewhere, here the Alto Rhapsody and Nänie seem the point of the whole adventure. The canon from Op. 113 is marvelous. Beethoven’s Coriolan chords and Bach’s Nach dir, Herr, verlanget mich explicitly prefigure the Fourth’s chaconne and variations. A delay preceded the Fourth’s release, and I looked forward more to the pre-show than the symphony itself. And what of the warhorses played on period instruments? The natural horns sound precarious. The first time through I feared they would crack and splinter in prominent places, as in the exposed duet in the Fourth’s second movement (2 before A, around 1:05). The strings’ portamentos arrive unexpectedly, as when the Allegro gets rolling in the First (mm 51-52, around 7:48), likewise when the strings take the melody in the Fourth’s second movement at letter B (around 2:33). Gardiner takes all the first movement repeats, which surprises most when the First rewinds. Overall, No. 1 made the biggest impact. Lacking the violin-heavy bombast, the Second sounds poorly knit, the Third somewhat nimble. Both opening movements are about the interplay between 2s and 3s, and require rhythmic command and fluidity. As compared, among others, with Jochum’s Third (Theorema TH 1212270) it’s clear that Gardiner’s Révolutionnaire et Romantique strings are stretched to their limits. What with Brahms’ overloading of his symphonic sonata allegros, each symphony’s subsequent movements play as more relaxed, especially where Gardiner’s winds produce interesting color. The stately pacing of the Fourth’s theme and variations approaches somnambulism.

Albert ROUSSEL: Symphony No. 1, “Le poème de la forêt” (1904-06); Résurrection — Symphonic Prelude (1903); Incidental music from Le marchand de sable qui passé (1908). Royal Scottish National Orchestra, Stéphane Denève (cond.). Naxos 8.570323 (http://www.naxos.com/). Albert ROUSSEL: Symphony No. 4, Op. 53 (1934); Rapsodie flamande, Op. 56 (1936); Petite suite, Op. 39 (1929); Concert pour petit orchestre, Op. 34 (1927); Sinfonietta, Op. 52 (1934). Royal Scottish National Orchestra, Stéphane Denève (cond.). Naxos 8.572135 (http://www.naxos.com/). I hear Roussel as an exemplar of angular neoclassicism. He came to music following a career in the French Navy, studied with D’Indy at the Schola Cantorum, and four years on was proficient enough to become a teacher of counterpoint. Martinů, Satie and Varèse were among his students. Departing from initial Impressionistic impulses, and abetted by a tendency toward polytonal counterpoint and Teutonic thickness, Roussel’s latter output can sound driven and coarse. Naxos has completed its four-disc orchestral Roussel collection. The Second was covered here. I revisited Naxos 8.570245 to shake my original disappointment with the series’ crass and hurried Third. Where I expected to have been as unenthusiastic about the similar Fourth, I found warmth. The impish Rapsodie flamande may be the disc’s best offering. Even for Roussel fans, the similar Petite suite, Concert and Sinfonietta will tend to coalesce despite Denève’s commendable concision. With its casual swirl and immediately repeated phrases, the First offers a forest’s four seasons bearing an Impressionistic stamp. After the Fourth one hears hints of burgeoning sternness. Inspired by Tolstoy, Résurrection is Roussel’s first orchestral essay. Four selections from the “Sandman” incidental music complete the disc.

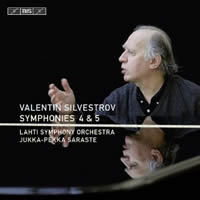

Valentin SILVESTROV: Symphony No. 4 (1976); Symphony No. 5 (1980-82). Lahti Symphony Orchestra, Jukka-Pekka Saraste (cond.). BIS CD 1703 (http://www.bis.se/). Distributed in the US by Qualiton (http://www.qualiton.com/). Silvestrov, who once ran with the avant-garde, soon enough backtracked. The Ukrainian is no imitator, but rather a philosophical annotator. Detractors who want their Romanticism unadulterated will be frustrated by the composer’s “post-symphonic” style. Appropriating the Mahlerian backlot’s contents, Silvestrov perpetuates the Weltschmerz of the Ninth and Tenth’s Adagios, along with the aura of the Fifth’s Adagietto. It’s not as though Silvestrov wants to live in ca. 1900 Vienna: Rather, he stands sentry over the Big Symphony’s remains. The Fourth is a mean, pessimistic essay rich in 1970s dissonance. Everything sounds familiar, but not quite. The lugubrious music is not exactly sickly. The Fifth commands attention. Filling nearly three quarters of an hour, it occupies a higher plane. Silvestrov operates in slow motion, infusing the music with Mahlerian gravitas, static harmonies and hesitant progressions. The listener soon becomes accustomed to touring basement archives. When a recurring modal folksong of antique demeanor leads towards sunlight, the effect is quite beautiful. Beyond the repetition and reflection, there are specific avant-garde elements that proclaim this a 20th-century work. Silvestrov frequently asks winds and brass to blow into their instruments without producing pitches — a gesture that ought to jar but doesn’t — aspirations that suggest drifting in and out of a coma. It’s as if Mahler banged his head during a Tyrolean hike and heard this when he regained consciousness. I’m aware of four other Silvestrov Fifths: dedicatee Roman Kofman and the Kiev Conservatoire Symphony Orchestra (BMG 74321 49959 2 with two pieces from Kitsch Music for Piano and String Quartet No. 1, rec. 1986), the Staatliches Symphonieorchester Estland under Arvo Volmer (col legno AU 31843, “Festival Alternativa, Moskau 9-23 October 1989,” with Gubaidulina’s Nacht in Memphis, rec. 1989), Andrej Borejko leading the Ural Philharmonic Orchestra, Yekaterinenburg (Megadisc MDC 7836 with Exegi Monumentum, rec. 1992) and David Robertson conducting the Deutsches Symphonie-Orchester-Berlin (Sony Classical SK 66 825 with pianist Alexei Lubimov in Postludium, rec. 1995). It’s easy to get lost in the Fifth. Had one of these five made jumps and cuts, I’d probably not have noticed. One section I compared appeared around 29’ in Robertson and 34’ in Borejko. The last time I discussed the Fifth, I admired Kofman’s blurred weightiness over Robertson’s fleet indifference. The classical-music aficionado ought to resist ranking performances like racehorses. That said, BIS delivers outstanding revelations outpacing the rest of the field. This recording’s clarity astonishes: The breathing noises, disruptive smears elsewhere, here become eerily transcendent. Saraste’s quicker pace snaps filigree into crisp focus without diminishing the single-movement’s fragility. Where I had been satisfied by Kofman’s lighthouse sweeping through the gray fog, Saraste builds bonfires, balancing gentle harp and piano against mourning strings, winds and brass. If I’m not mistaken, BIS’ notes are among the first to look beyond the obvious Mahler connection and unite Silvestrov with Scriabin’s unfinished Mysterium, Glass’s minimalist arpeggios and Tippett’s Fourth (1977). Though both symphonies are single spans with breathing sounds, this last comparison seems a stretch. As for Scriabin, Silvestrov’s language is markedly less sensual and more stolid, even though both may fling a contrasting bolt now and again. The archetypes are Germanic, neither French nor Russian. However, BIS suggests chords in Silvestrov’s Fith point right back to the Scriabin-Nemtin Preparation for the Final Mystery. Silvestrov: Symphony No. 5 (1980-82)

[More Grant Chu Covell, Mostly Symphonies]

[Previous Article:

String Theory 3: Viols and Violas]

[Next Article:

Olivier Greif 1.]

|