Bad Reputation

|

James Graham [April 2021.]

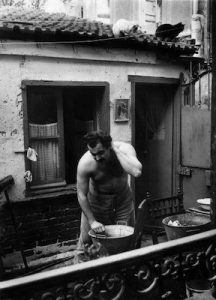

The music races by in just over three minutes but feels much faster. Imagining it was your first time hearing the song, it seems impossible to conceptualize the piece as any kind of protest. You’re trying to keep up with the lyrics, the gentle boum ba boum of the guitar bouncing in an insistent rhythm like a man in a hurry to get somewhere. He’s talking quickly like a stranger passing on the street. The whole thing is lighter than air, and barely underway, it’s over. It’s easy to regard the whole thing as a French trifle, hard to take seriously, maybe a song about love gone wrong. Another one of those things that just doesn’t translate. Is it a poem? A statement? Are you both spies headed to a clandestine meeting and the singer’s whispering in code? All of the above. In this town I don’t have to work hard But good people don’t like it All of which, if this were America, seems a set-up for a High Noon shoot out on Main Street between a Cool Guy and the Straights, an orgy of cosplaying hipsterism. Except that everything in the rhythm, the intonation of the voice, the whole ambiance of the song says no. The singer even manages to get in a few jokes. Everyone points the finger at me, he says, except the ones who don’t have arms. Everyone gives me a kick, except the guys who lost their legs. (And where might they have lost their arms or legs?) A little corny — that’s how it is in small towns — but the singer saves the most revealing bit for last: No need to be a Jeremiah But the good people don’t care for those Nowhere do we get the sense the singer is clearing out, that he’s headed to the bus station with his bags packed. It’s part of the seductive anarchy of the song that he appears to be staying where he is, under people’s noses. Everybody lives in a small town of some kind. Could be twenty thousand or five, a neighborhood in a city or a village nestled in the hills with all of 235 inhabitants. You can’t really move away. (Ten years or so later another chansonnier was in a similar mood: “If my thought dreams could be seen / They’d probably put my head in a guillotine.” That last word in the line from It’s All Right, Ma, is it just a smart rhyme or a tip of the hat between pros?) The song was written in the years immediately after the Second World War, when social conformity was at its height, when people were busy covering up how they’d survived the war. People had a lot of reasons to be on the right side of things back then, just like they do now. The stranger who wrote the song was born in the southern town of Sète, a small pile of rock topped with pine and cypress trees, laced with Mediterranean beaches on three sides. The singer didn’t take the well-traveled road to Rome but came by way of the Basdorf camp near Berlin, where he was doing forced labor — a one way ticket to physical exhaustion and death. A year into it, given a day off, he promptly disappeared, turning up in occupied Paris, where he stayed with his aunt Antoinette. That couldn’t last. He was a deserter and a big bear of a man, as maybe you can see in the photo above, liable to stand out in a crowd. In the waning days of ’44, that meant being shot if the police stopped him on the street, and quite likely the same for his aunt. Looking for a place to hide he found a narrow little alley in the 14th, quartier Plaisance, where an older couple, Jeanne and Marcel Planche, took him in, giving him the cot in the corner of a house with no electricity, gas or interior plumbing, where dogs, cats, a turtle, a buzzard and a lonely mother duck outnumbered the humans. Impasse Florimond or Florimont (the signs disagree), sounds a little like florilège, a medley or florifère, abounding in flowers. None of that. It was named after a certain Monsieur Flowery World or Flowery Hill. Back in the days of summary justice, Florimond was the local church executioner who strung his victims up along the road running to Vanves and Montrouge. That practice lasted until Louis XIV took the privilege of hanging people for himself. None of which, we can guess, the stranger knew or much cared about while he lived there, forming a lasting attachment to the place, the people and the brutes, making it his hide-out for the next twenty odd years. Toss another unintentional irony onto the pile for the guy who picked up a banjo and started to write Bad Reputation. He sat on his lyrics for a long time before he was convinced they were ready. In 1952, during a party at the home of the Parisian singer Patachou, Georges Brassens, 31 years old, made his debut with the song Mauvaise Reputation. The frequent opener at concerts throughout his career, it became the title of his first album and, according to him, his credo as an artist. The song was given top honors on the airwaves — it was immediately banned, much like Vian’s Deserteur a few years later. As is usually the case, censorship had the reverse effect. (Stretching credulity just a little, Pierre Nicholas, who met Brassens that night chez Patachou and became his long-time bass player, was born on Impasse Florimond before the war.)

Georges Brassens in concert at the Théâtre national populaire, September-October 1966 (Roger Pic, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Brassens_TNP_1966_f13.jpg). Further down the road, the Academie Française gave Georges Brassens the Grand Prize for Poetry in 1967. (Fast acceptance for a folk singer, say what, beating the Nobel Committee by forty years.) That’s some journey from the Impasse. While recording 200 hundred songs of his own, he also set poets like Victor Hugo, Paul Fort, Louis Aragon, Verlaine, Jean Richepin, Alfred Musset, Jacques Villon and half a dozen others to music. The Impasse is cleaned up now but it’s still hard to find, hidden to the side of a gas station off rue d’Alesia. There’s a plaque for Brassens, and one for Nicholas, too. Brassens’ reads, “Et que j’emporte entre les dents un flocon des neiges d’antan.” (“May I carry one of yesterday’s snowflakes between my teeth.”) A line from one of his songs, and a nod to Villon, who also feared being hanged. Those are a few of the things that went into that one song, a tune that only sounds off the cuff. Of the three or four figures most responsible for reimagining French chanson in the years after World War Two, Brassens travels least. Everyone in the English-speaking world knows Jacques Brel while hipsters can claim Gainsbourg for their own. That leaves Brassens and Leo Ferré, the poet-composer of Ni Dieu Ni Maître. Where Ferré is outspoken, Brassens is an almost homey everyman who rarely calls attention to political beliefs but lives as he pleases. In any case, passing over a life’s work that many French, those temperamental anarchists, know by heart, let’s race to the end, when Brassens was thinking about his old hometown. His poem, Supplique pour être enterré dans la plage de Sète (“Request To Be Buried On The Beach At Sète”), gives the Grim Reaper a run for his money, gently mocking the petits catastrophes of humankind, telling little stories about shipwrecks and sea maidens, crowded family vaults, dolphins, his first romance on the beach. Where the language of Bad Reputation is spare, Sète is extravagant. Brassens was seriously ill when he made his last tour of France, singing and playing Sète to rapturous applause. I offer it here in an unrhymed version that only tries to catch some of the images and feeling. I’m sure you can find better, but I did this one quickly, just to get it down. Paul Valery, a poet on the other end of the spectrum in sensibility and renown, is also buried in Sète. The Grim Reaper’s had it in for me Dip your pen in the blue ink of the sea When my soul has taken flight to the horizon The family vault, alas, is nothing new. At the edge of the sea, two steps from the blue waves A beach where, even when he throws a fit It’s there, once upon a time, that fifteen years flew by. With guarded deference to Paul Valery A tomb sandwiched ’twixt sea and sky Is this too much to ask? On my tiny patch of ground Some from Spain, some from Italy And when she uses my heap to rest her head Poor kings and pharaohs too! Poor Napoleon! * * * “Anti-conformista por adentro, no por afuera.” So says Paco Ibañez before his lovely, singalong version of Mala Reputación. He calls Brassens the Johann Sebastian Bach of the chanson. You can find Mauvaise Reputation here and Enterré à Sète here. Take a look around for Brassens’ settings of the French poets. I’m indebted to Titi for some of the old photos. You can visit her Brassens pages here. And now that I think of it, isn’t there more than a bit of shared feeling between Brassen’s Sète and Dylan’s Tambourine Man? Both share that special sensibility the beach evokes, of exuberant freedom and defiance of convention.

[More James Graham]

[More

Brassens]

[Previous Article:

EA Bucket 30.]

[Next Article:

Used Bin Troll Tweets YY.]

|