Boo Hoo

|

Ethelbert Nevin [August 2007.]

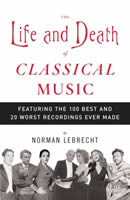

The End Is Near! The End Is Nearer! The End Was Last Week! Let’s give it up for Norman Lebrecht! A-plus for tenacity! The man’s been chronicling the end of the Big-C (classical music) for nigh onto half an eon. Perhaps with The Life and Death of Classical Music: Featuring the 100 Best and 20 Worst Recordings Ever Made he finally gets it right, but I wouldn’t bet the family silver. With his victorious ensign perched atop classical’s self-immolating recording industry — Götterdammerung’s final bars sounding in the background — Lebrecht withdraws his pistol from its fine leather holster to deliver the coup de grâce. To hear him say it, the whole endeavor, from electrical recordings through LPs to CDs is doomed. It has been a business awash in sycophants, big egos and gross miscalculation. And it’s gone, over, finished. Never again. Rich in anecdotes and recollections, Lebrecht’s book entertains much as that movie about the Titanic. We know where the action ends, but getting there is most of the fun. It’s hard to believe that major-label bosses have been as greedy and stupid as Lebrecht suggests. He cites statistics to show that the industry’s prevailing currents swept money into the nets of a persistently precious few. As a cautionary tale, a more careful economic analysis could help prevent other mismanaged industries’ demise. A few bits to mull over:

Lebrecht appears to carry a grudge against Peter Gelb, onetime head of something or other, now the Metropolitan Opera’s head honcho. In his list of 20 worst recordings, he hammers at Britten and Pears’ Winterreise (No. 7). Was he once snubbed at the Aldeburgh Festival? Turned away from Snape Maltings? A favorite of mine appears as No. 14: Kremer and Marriner’s Beethoven Violin Concerto with Schnittke’s cadenzas. It’s unclear whether Lebrecht disdains the polystylistic additions or Philips’ omission of Schnittke’s name from the release’s marketing effort. No. 18, Reinbert de Leeuw’s starter kit for Satie’s Vexations (play the CD 15 times), offers an excuse to trash-talk Ferneyhough and Xenakis, among several unfortunate others: Sony boss Norio Ohga warbling through Fauré’s Requiem and Nimbus’ backer, Count Alexander Numa Labinsky, moonlighting in Schubert lieder as Shura Gehrman. As a recurring deficiency, Lebrecht often halts as soon as he concludes a colorful anecdote. I wish he had made larger claims about our economy and culture. It’s true that some unexpected bubbles topped the charts — Gould’s first shot at the Goldbergs and Górecki’s Third as examples — yet there’s little discussion about what appetites these fed, or why they are rarely repeated. Lebrecht does mention Naxos, one of the industry’s current stars, but fails to draw conclusions. Shunned at its conception 20 years ago by those whose world revolved around Decca, DG, EMI and Philips, Naxos today stands as one of the industry’s most adventuresome and intelligent forces. CDs are but one format. Naxos makes its vast catalogue available via digital download to individuals, libraries and educational institutions. They’ve forged inroads in the music licensing business. Most importantly, they’ve made money marketing lots of recordings rather than relying on blockbusters. And that, in fact, is a successful label’s secret — which Lebrecht fails to note or applaud. The classical-music biz isn’t dying. It’s equalizing itself, turning to small niche endeavors with their lower entry barriers and greater chances of breaking even or turning a profit. Instead of one star-studded release aimed at pleasing everyone, we have a vast range of morceaux directed at niche audiences. There are no middlemen to keep me from Altarus’ Sorabji, mode’s Cage or Tzadik’s Zorn. When I buy a CD, I want the musicians to see my green. I’m not here to fill the tank of an A&R rep’s jet. Further, I trust small-label managers to keep good things coming and will, on well-earned trust, try something new. Even orchestras have hung up their own shingles and exhumed their archives. What we really need is good, sharp, insightful criticism. The 100-best-of and 20-worst-of essentially operate as frivolous entertainment. Criticism educates by helping naïve as well as experienced record buyers make their decisions. Lebrecht’s lists are mere springboards for stories and gossip — harmless fluff which will fall out of favor as surely as the industry he purports to document.

[More Ethelbert Nevin]

[Previous Article:

Words Fail Me 2.]

[Next Article:

Words Fail Me 3.]

|