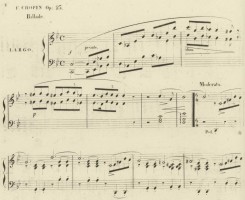

Chopin’s G minor Ballade, Op. 23

|

Beth Levin [January 2003.]

A look inside . . . Largo, 4/4 A noble C climbs four octaves in A flat and touches a high C (C6) before descending by graceful turns into G minor, the true key of the Ballade. In its lilting, fragile beauty, the statement of the opening phrase contains the germ material for the rest of the opus. Often one finds in the earliest measures a clue to understanding a work as a whole, and in that sense and for the purpose of analysis, much of the music can be considered a theme and variations. A rhythm of 6/4 suggests an underlying waltz, as does the set of chords that plays off each melody note. Further, the chords lie under portamento slurs which give them shape, gently tug at the second and third beats, and increase the inherent dance quality. However, a waltz in G minor is colored by the key and therefore imbued with a tender poignancy. One dances, but with a heavy heart. The accent on the first note of the melody is important, propelling the next five eighth notes to the downbeat while adding richness to the note itself and a subtle, harmonic effect to the phrase. A forward-moving bass line and rich chords in the treble increase the musical intensity and culminate in one of Chopin’s spectacular embellishments — 18 filmy notes against solid quarter-note chords. I remember my early teachers lining up the glittery grains to match each chord, but in the end a performer needs a sense of sweep and fearless execution to achieve the Nureyev-in-midair effect of the ornament. Already Chopin has turned the opening notes topsy-turvy to create a new bass line, thus unifying and sewing together elements in the music. It is this quality that ultimately allows the Ballade, a fairly unstructured form, to be utterly convincing — that and the realization that the material itself is of the highest art. Still at work in G minor, Chopin urges the music forward with two-note slurs, the markings agitato and sempre più mosso, accents above each octave and a rhythmic bass line that acts as a trigger for the treble, over and over. In human terms this translates to a yearning cry. Now amidst forte and breathless speed the music whirls furiously in a wash of G-minor arpeggios until calando and smorzando signal the performer to slow, to ebb and finally to ritenuto to the sublime second theme of the Ballade. Meno mosso / sotto voce (a lessening of time and sound) The second theme presents itself as a love song in E-flat major. Chopin mines his own material from the opening melody and gives it a new shape and character. Pianissimo is the hushed context of sound for the theme against a bass of arpeggios. Specific notes of a quarter or a dotted half in duration add importance as a secondary melodic figure. Other notes with accents act in counterpoint to the main theme. Chopin’s love of Bach is always evident. Nothing is ever solely an accompaniment because of the intricate middle voices, notes that add a second and third line for the subliminal ear to follow. Another reframing of the opening material occurs. Sforzandi (sharp accents) and a buildup of small crescendi in stretto create a foreboding quality that is fulfilled on the arrival of the transformed second theme. No longer a song of love, the material becomes majestic, in ff, the melody in octaves, chords replacing single notes of the bass. The original chords that accompanied the opening theme are now feverish, nearly frightening. Chopin uses his material in a fresh way to portray mood. Virtuoso octaves embellish and open the music to new heights of passion. But one must be careful not to think in Lisztian terms. Chopin’s keyboard grandeur is never mere effect — every note of a running scale is spoken and a poetic sensibility never falters for a second. A rumble of quick notes marked più animato leads temporarily to a section of scherzando writing. Here is the pure pianistic dazzle that pervades the Ballade but never robs the crucial element of each note. Nothing is fluff. Leggiermente (extremely light) is the marking in the middle of relentless running eighths, again, certain notes elongated to bring out a significant line, melody or second voice. In one fearless plunge of scale, Chopin returns us to the second theme in E flat, now with a pulsating force, the melody in handfuls of ff chords, and the bass in expressive, richly arpeggiated patterns. One more transition will occur to meno mosso, pp, sotto voce (half voice) before the onset of the thrilling coda. Throughout, pp (very soft) and ff (very loud) suggest more than a sound level, a mere dynamic marking, and challenge the performer to create an emotional equivalent — ff perhaps a wild ferocity, pp a tender sigh. Let me say here that Chopin’s transitional material linking sections of the Ballade is some of the most elegant, poetic and challenging music a performer will ever face. How one plays with time and sound to execute the transitions may be at the heart of whether the performance succeeds or fails. The coda, marked Presto con fuoco, is jagged, lyrical, wild and a bit maddening too as the accented chords alternate with single notes in the treble over a bass that hops, darts and never rests. One must keep one’s musical head or collapse in the middle of the dust storm. After an ascending G-minor scale in tenths, a fraction of the original theme is heard; a second, longer run evokes another quote from the theme. The finale is one descending line of fierce octaves in triple forte to a penultimate G, a chordal cry in G minor and a final G under a fermata. My advice would be to sit on the G, linger, and be grateful. [As with her Schumann and Beethoven guides, Beth helps one to experience the piece anew. Everybody has recorded it; ArkivMusic (http://www.arkivmusic.com/), an efficient mail-order service, shows 114 versions. Gulda’s 1954 reading is fleet (7:52) but very scrupulous about details. In the slow camp, Moravec (10:06) displays profound insights. Cortot’s June 7, 1929 account (8:50) should be heard. W.M.]

[More Beth Levin]

[Previous Article:

Salvatore Sciarrino's Chamber Music on Kairos]

[Next Article:

Revolving Doors on Madison Avenue]

|