Copland and Me: Two Concerts and a Recording

|

[Steven Richman is conductor of the Grammy-nominated Harmonie Ensemble/New York, now in its 25th season. Their new CD, Copland: Rarities and Masterpieces, has recently been released on Bridge Records 9145. Ed.] Steven Richman [June 2004.] On Saturday, November 22, 1980, a 14 1/2-hour concert took place at New York City’s Symphony Space on the Upper West Side, one of the first Wall-to-Wall Concerts. Celebrating the 80th birthday (actually November 14) of Aaron Copland, it included works by the birthday boy, as well as from other American composers. The event was broadcast on WNYC-FM and National Public Radio, and portions were included in a Copland video which was broadcast worldwide. A year before the concert, in 1979, I had founded Harmonie Ensemble/New York, comprised of colleagues from major New York orchestras, including the New York Philharmonic, Metropolitan Opera, New York City Opera, New York City Ballet, and Mostly Mozart Festival, and our first concert had taken place at Symphony Space. When I learned that a Copland 80th Birthday Concert was planned, I jumped at the chance to participate. To be involved in such an historic occasion was a dream come true. I had seen Leonard Bernstein conduct Copland on the Young People’s Concerts on television, particularly the Dance from Music for the Theatre, as well as with Copland himself performing the Piano Concerto. Classical music was then a very exciting place. Previous to the 1980 Copland Concert, I had conducted a variety of composers with HE/NY, including Rossini, Stravinsky, Beethoven, Wagner, Mozart, Cherubini and Dvorak, but this was my first opportunity to conduct Copland. Coincidentally, an orchestra in which I played (I was originally a French horn player) was to perform another Copland birthday concert in Carnegie Hall just previous to the November 22 event. That concert included Copland conducting the Dance Symphony, and Bernstein conducting Lincoln Portrait, with the composer himself narrating. So I did have an opportunity to introduce myself and chat with Copland beforehand. The work I chose to conduct for the 80th Birthday Concert was Music for the Theatre. Copland was to conduct the ballet score Appalachian Spring, in its original 13-instrument version, of which he had finally done the first recording in 1973. These two works were to be the climax of the daylong concert, ending a virtual marathon of distinguished American music performances. Twenty-two years were to pass before I was able to record the pieces we performed together. I had the priceless opportunity to work directly with the great man that week previous; both Copland and I conducted Harmonie Ensemble/New York in the final two works on the program. Copland attended my rehearsals, and I closely observed his, making copious notes in my score. I was fascinated to hear his comments, with the very specific ways in which he wanted Appalachian Spring to sound, and not sound. He often said, “No Tchaikovsky!” wanting it to sound more “American,” not sentimental. And “Don’t play it warm, it’s already warm.” At the end, he wanted “no vibrato, like a prayer, with a special quality, like an organ.” I can still hear his distinctive voice in my ear. There was a great deal of excitement that week in New York in anticipation of the big event. On the concert day, I listened to much of it on the radio, closely following its progress. That night, I arrived about 10 p.m., and could hardly get in the door, since a long line went around the block at Broadway and 95th Street. It was free to the public, and everyone wanted to get in; many weren’t successful. When I finally did enter, it was packed to the rafters. To my surprise and delight, Leonard Bernstein showed up. I had played in orchestras with the Maestro several times, but this was a very different occasion, and I was no longer a “sideman,” but bore a greater responsibility. L.B. had just arrived from a reception at the Waldorf Astoria, where the new Grove’s Music Dictionary had been introduced. At the time, it cost over $2,000. “Who can afford it?” he asked. If anyone could, certainly he could have. Bernstein then remarked that it was the 17th anniversary of the Kennedy assassination, and there was only a small mention in the back of the New York Times. He then went on to say, “Well, we shouldn’t dwell on the negative, we should be happy it’s Aaron’s birthday. Where is he? He must have gone to take a pee!” Half the audience laughed and half gasped. Who knows what the reaction was of the radio listeners? And remember that this was 1980, when our tolerance was less than we have become accustomed to today. What an intro! So out I walked in front of this semi-stunned, packed audience to lead Music for the Theatre. Copland had composed it in 1925, shortly after his return from three years of study in Paris with Nadia Boulanger, mentor to a whole generation of American composers. But Copland was her favorite student at Fontainebleau, and he had met Stravinsky, as well as Poulenc, Milhaud, and even Saint-Saëns at Boulanger’s musical soirees. When he returned to New York, at the instigation of Boulanger, he was to compose a Symphony for Organ and Orchestra (later called Symphony No. 1) to be performed by the New York Symphony under Walter Damrosch. When the premiere of the daring, dissonant, and angular work took place in 1924 in Aeolian Hall, Damrosch remarked to the audience, “I am sure you will agree that if a gifted young man can write a symphony like this at twenty-three, within five years he will be ready to commit murder!” Newspapers carried the byline “Young Composer to Commit Murder.” Copland reveled in telling this story for the rest of his life. Copland’s second work after his return, a complete turnaround, was Music for the Theatre. Remember that in the few years previous, Stravinsky and Milhaud, among others, had incorporated American jazz into their music, and Gershwin had composed his Rhapsody in Blue in 1924. Claire Reis, on behalf of the League of Composers, had requested a work from Copland to be premiered by members of the Boston Symphony Orchestra under Serge Koussevitzky. It was the very first work to be commissioned by the composers guild. And to be performed by Koussevitzky, the great supporter of new music by Ravel, Bartók, and many American composers, was a very great honor. Music for the Theatre was first performed in Boston on November 20, 1925, and soon brought to New York’s Carnegie Hall and other venues by Koussevitzky. Copland already had major performances by two of the preeminent orchestras in the U.S. under his belt by the age of 25. Rather than on a specific play or show, Copland based his work, his first consciously jazz-influenced one, on a general impression of the vibrant New York theater of the 1920s, particularly the 42nd Street burlesque houses. And he called it “Suite in Five Parts for Small Orchestra” (rather than the traditional movements). The second part, Dance, features a quote from the popular 1904 song, “Sidewalks of New York,” specifically “East side, west side,” played by the bassoon. The fourth part, Burlesque, was partially inspired by the comedienne Fanny Brice. On hearing the piece, composer Roy Harris jumped up, exclaiming, “It’s whorehouse music, it’s whorehouse music!” Imagine the reaction of staid Boston and New York audiences accustomed to Brahms, Beethoven, Mozart, and Tchaikovsky, when they heard this brazen, bawdy, jazzy music! When Koussevitzky soon brought the work to the Brooklyn Academy of Music, after the performance, organizers of the concert complained to Koussevitzky of the work’s modernism. But Koussy suavely replied, “But gentlemen, Copland is one of your boys. I played it here to do honor to your city.” (Copland had grown up in Brooklyn.) Copland certainly had in mind the pit orchestras of the period. The score specifies, besides the mostly single winds, brass and percussion, only “minimum number of strings” as nine: two first violins, two second violins, two violas, two cellos, and bass (2-2-2-2-1), with the caveat “In large concert halls the strings may be increased at the discretion of the conductor.” In Copland’s 1965 WGBH-TV broadcast of excerpts on “Music of the 20’s” with members of the Boston Symphony, he used 14 strings (4-4-3-2-1), the complement I decided on for my concert and recording. Most recordings utilize a symphony-size string section, which gives a very different impression of the work. In addition, at the final mastering session for my disc, I was faced with the decision of what possible reverb to add. In the end, I opted to use the “raw” sound of the original recording, since I felt it was the most natural, and best suited Copland’s intentions, rather than augmenting it into a Mahler symphony. During our rehearsals for the 80th Birthday Concert, it became apparent that Copland had a memory problem, although he was collaborating at the time on what was to become a two-volume biography. His recollections of the past were clear, but his short-term memory was faltering. When I finished conducting Music for the Theatre, as I walked offstage, I almost tripped over Copland, who was sitting in the wings in the dark. He looked up at me and said, “That was the best performance of Music for the Theatre I ever heard! Did you conduct it?” I was surprised, and thought he was joking, but seeing no trace of a smile on his face, I said, “Yes, Mr. Copland. Remember, we worked on it together?” He replied, “Oh yes, I remember.” The circumstances of the genesis of Appalachian Spring are well-known, but bear repeating. Copland was commissioned by arts patron Elizabeth Sprague Coolidge to write a ballet for the renowned choreographer Martha Graham, who provided Copland with a scenario. Copland worked on it in Hollywood and Mexico, completing a piano version in Cambridge, Massachusetts in 1944, and finished the instrumentation in New York City and Fire Island in July of that year. Copland’s working title had been Ballet for Martha. In fact that is how the original manuscript is inscribed. But the day before the premiere on October 29, 1944, Graham told him that she had decided to call it Appalachian Spring, based on a phrase from Hart Crane’s poem, “The Bridge.” “It really has nothing to do with the ballet,” she told Copland, “I just liked it.” Later, Copland often amusingly told of the many times audience members would come up to him after a performance and exclaim, “Oh, Mr. Copland, I can just see and smell the Appalachians in Spring!” The premiere of the ballet took place in the auditorium of the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C. Since the pit was very small, Copland composed the ballet originally for a 13-instrument complement of flute, clarinet, bassoon, piano, and strings. Shortly after the great success of the premiere, Copland arranged it, as well as a suite for symphony orchestra, in order to make it more available to orchestras and accessible to audiences; it has become the most popular of Copland’s larger works. I personally prefer the original chamber version, since I feel it retains the intimacy and better captures the spirit of the ballet. Copland loved them both, as his progeny. Last on the program of the Copland 80th Birthday Concert was the composer himself conducting the original version with Harmonie Ensemble/New York. His conducting was certainly not impaired, and the performance was quite wonderful, even better, I thought, than his commercial recording. It was a magical moment, and following the heartfelt ovation at its conclusion, a huge birthday cake was wheeled out, and the 1,000-strong audience sang “Happy Birthday” to the greatest living American composer. Afterwards, in the green room, Copland signed both the program and the Appalachian Spring score for me, which I treasure. Serendipitously a photo was taken, which graces the back of the CD. Copland became Laureate Advisor to HE/NY, a post he held until his death in 1990.

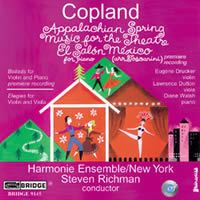

Cover of Bridge 9145 For over two decades I dreamt of recording these two masterworks, since I felt a certain responsibility to realize and pass down Copland’s intentions and ideas as to how he wanted his music to sound. And following 9/11, I likewise felt a strong need to perform and record American works, since I had concentrated for some time on European composers, including Stravinsky and Dvorak. America had taken quite a beating in the international press, and I wanted to remind us and the world of our beautiful and singular cultural achievements. So finally in February 2002, I conducted HE/NY in an all-Copland program in New York City. We recorded it over the next few days at Purchase College in Westchester, just north of the city, and not far from Copland’s home in Peekskill, which is now maintained as Copland House. Even though he had passed away 12 years before, I felt his presence at the sessions. Each of the three chamber works on the program is unique. Two Ballads for Violin and Piano derived from a never-completed 1957 violin concerto for Isaac Stern. They were edited in 1986, with Copland’s blessing, by pianist Bennett Lerner, and my friend, the composer Phillip Ramey, who was both Copland’s and Bernstein’s assistant. The Ballads (“not Ballades,” Copland specified) were premiered at an 86th birthday concert near his home. What a shame Copland never completed the concerto, but how fortunate we are to have these two small gems. They are quite lovely and affecting, and were beautifully played, and recorded for the first time, by Emerson Quartet violinist Eugene Drucker and pianist Diane Walsh on our CD. A Copland rarity, Elegies for Violin and Viola dates from 1932, and was written in Mexico, partially inspired by the death of the poet Hart Crane. In Copland’s more severe style, they were premiered in 1933 at the 10th Anniversary Concert of the New York League of Composers. (Interestingly, other string duos on the program were by Prokofiev and Alexander Tcherepnin.) Copland later used material from the Elegies in his Statements for Orchestra and Symphony No. 3. They receive an intense and moving performance by Eugene Drucker and his Emerson colleague, Lawrence Dutton. Certainly the most unusual work on the CD is another premiere, though an unlikely one. Copland’s El Salón México, begun at the same time as he was writing Elegies, was a reminiscence of his memorable visit to a Mexico City dance hall of the same name. Copland used four Mexican folk songs in it, and it was premiered in 1937 in Mexico City, conducted by Carlos Chávez. Koussevitzky led its first American performance the following year, and it became Copland’s most popular piece to date. In 1942, Arturo Toscanini conducted El Salón México with the NBC Symphony. This was a relatively rare occurrence; Toscanini’s repertoire of American composers was somewhat limited, although he eventually conducted works by Gershwin, Siegmeister, Barber, Creston, Gould, Loeffler, Grofé, Harris, etc. However, Toscanini may have been performing American music in part as a form of thanks to the country which had provided him with personal solace and artistic opportunity. Quite by accident I discovered, in the Toscanini archive in New York City, a piano arrangement of El Salón México in Toscanini’s hand! It was apparently done for study purposes in order to familiarize the conductor with the tricky Stravinskian rhythms and help him get the score into his head and hands. Never intended for performance, it certainly is a unique document, which clearly reflects the composer’s intentions. A copy of the manuscript was given to Copland by Walter Toscanini, the conductor’s son, in 1961. There were several small errors, and the score was rather “bald,” and would sometimes require three hands to play (like Copland’s piano reduction of Appalachian Spring). I edited it so that it could be performed more comfortably, also adding relevant original orchestral markings to provide a more accurate and authentic presentation and recording. I was also fortunate to have the kind support of my friend, Walfredo Toscanini, the Maestro’s grandson, in this labor of love. Diane Walsh, who played the first performance and premiere recording, did a superb job, as all who have heard it heartily agree. It has been a gratifying experience for me to assemble this unusual program of Copland works with which I have had a direct connection. It took almost a quarter of a century to realize my dream of releasing a recording of the two major pieces on the CD, and the two premieres and a rarity are the “icing on the cake,” so to speak, 24 years removed. I think he would be pleased.

[More Steven Richman]

[More

Copland]

[Previous Article:

Listening to the Radio. Again.]

[Next Article:

La Folia Lost a Dear Companion]

|