Creating in the Moment: A Q&A with Beth Levin

|

Gil Reavill [January 2016.]

GIL REAVILL: You’ve recently released two CDs recorded in wildly different environments. Beyond the specific studio situations, did you find geography influencing performance? Brooklyn’s modernist cacophony versus Vienna’s weight of history? BETH LEVIN: The Vienna recording, which happened first, took place in a militia building, of all places. Men in uniform were everywhere. They all seemed to know their Schubert and were attentive and kind. During the breaks we would have coffee and relax. In the room where the piano was housed, there were huge gilt-framed portraits of generals and battle scenes on the wall. It felt a little like the equivalent of an Independence Hall in Philadelphia. [The official name in English: Hall of Honor of the Austrian Armed Forces at the Catholic Military Parish Church.] The piano was a rather sweet-sounding Bösendorfer, which I think was a good match for Schumann’s Kreisleriana, the C Minor Sonata of Schubert and Versione (1973) of Anders Eliasson (1947-2013). The bass was powerful and yet one could coax a beautiful singing line in the treble. The international recording team was excellent, in that I felt they had good ears and a very pure sensibility. We didn’t actually exchange much conversation per se, but they relayed to me a sense of enormous empathy and professionalism. My producer was the one to interact with them directly. I had just performed the program twice in Munich the week before, and was probably in a half-exhausted, half-elated state of mind. I managed to see some of Vienna on free days, thanks to my host, but I think that the recording became the theme of the trip and overpowered other experiences. The Brooklyn recording took place on Douglass Street, a mile from my apartment in Park Slope, Brooklyn. The recording engineer and the producer were both old friends. As a result I suppose the whole feeling of the sessions was more familiar than in Vienna. Yet the same tension was there and the same desire — that the music spring to life and come into being in the specific moment of recording. I remember having to stop because of loud noises coming from a huge Mack Truck outside the studio. And in Vienna there were laborers outside described to me as “tree fellers.” Perhaps the best contrast between the two experiences exists right there.

Inward Voice was more or less a live studio recording. How did you proceed? In both recordings the idea was to try to keep things whole. So even in the Schumann works (Kreisleriana and Davidsbündlertänze), which are made up of many small character pieces, we tried to get at least one whole take before going back to repeat a movement here and there. One important issue is timing. In a live performance, the timing between movements is crucial. We wanted to keep that sense in the recordings as well. As you study Kreisleriana, for instance, you start to see that certain of the small pieces belong together in order to make sense musically. We didn’t want to lose that aspect of the performance. Before making Inward Voice for Aldilà Records, I had only released live concert recordings. This was actually my first experience recording in a studio as a soloist. I had done that only with chamber music. With both of the sonatas — Schubert and Chopin — we did whole movements at a time, with only the sparest of corrections. Both Eliasson works were performed whole. I think the repetition of complete movements was difficult, but I am happy we had those intentions. Often what happens is that the third or even fourth play through turns out to be the best take.

“My job of being a musician in a recording studio has nothing to do with being a musician on tour performing.” So says Moby. What’s different and what’s similar about the two gigs? Recording in the studio does have a kind of containment to it, one you almost have to bypass in order to achieve the spontaneity that is built in when you are onstage. In a live performance you have that one chance to express the music, with the audience adding even more life and risk to the situation. But the red “on air” sign of the studio can feel just as crucial and in-the-moment. I did get the sense that the recording sessions in Vienna were a bit more studied than my stage performances had been even a few weeks before. But I don’t think it was a flaw — simply another way of expressing. Touring requires a different sense of pacing, with much down time to relax and even forget about the music. Studio playing is very compact, as if you were condensing days and days into a few hours. But whether onstage or in the studio a performer is creating in the moment.

What teachers, mentors or influences look over your shoulder in the studio? What ones are different for different works, what ones are always there? I had heard my teacher Leonard Shure play the C Minor Sonata, D. 958 in class many years ago and it was memorable. I never thought I would ever play that work, it being so large and requiring such power. Shure had a huge sound and a musical mind that would leave you looking at a visual structure after he played a work. I had been working with the German conductor Christoph Schlüren on the pieces that make up the Aldilà CD, and he was the producer for the recording. He was literally standing over my shoulder, which I had never experienced before. His understanding of the repertoire was so encompassing and sharp that it affected my performances deeply. Again, I tried never to lose my own instincts, personality and spontaneity. Christoph opened up the language of Eliasson for me. I think by the time of the recording, the piece really blossomed and went off into the right realm. I am ever grateful that my teachers have all been brilliant — the deepest thinkers and feelers at the instrument. I hope that in my own voice I have taken inspiration from them without copying.

In a single recording date, you might perform pieces with wildly different moods and textures — Kreisleriana, for example, and then the Eliasson. How do you avoid creative whiplash? I think contrast is something that’s second nature to a musician. Once you have studied Beethoven, in particular, you develop a knack for the most sudden changes in dynamic markings — as in his famous subito pianos — and the most dramatic transformations. Schumann as well is famous for quicksilver changes — as in Florestan and Eusebius, one character wild and outgoing, the other inward and brooding. It is an easy next step to extrapolate to playing works of totally different nature. Most recital programs tend to contrast — emotionally, in period, in texture — but the execution of it needs to come from the performer, who is adept at calling on a vast emotional palette.

Brian Eno said it was the art school students who were behind the explosion of recording technology in the 1960s, because music students were locked into the idea of ephemeral performance, while art students could see music as painting, as possessing permanence. How does this “one for the ages” enter into your studio experience? That’s funny, because I’ve always envied friends who paint and are done when they hang the show and people come to the exhibit. A pianist’s work just begins at the opening of the concert. It can’t be wiped away and begun again. For a long time I preferred music to simply fly out to the atmosphere. I still do, although it’s so nice to have a facsimile of what happened in performance. A recording can never truly recreate a performance. That said, I’m always thrilled to find great vintage pianists on YouTube: Schnabel, Lipatti, Richter, Shure, Serkin, Sofronitsky, Yudina, on and on — including people I never would have heard play live. Not to mention the great singers and string players from whom I think a pianist can learn so much. One line sung by, say, Jussi Björling can be life-changing for a pianist.

Related to that, how do feel after a live performance when you wish you had the tape rolling? A friend told me that he thought a performance of the Aldilà recital pieces performed at Bargemusic just before the recording date was wonderful. I have no record of it. I always feel a little sad when that happens. But you can’t always tie music down or put it in the can, so to speak. Sometimes it’s nice to let the music go, even when it may be the best rendition of the works.

What is it that would make a recording date stand out? How do you gauge the success of a studio session? In the end I think other people may be the best judges of a recording. One gets so close to it, listens for every molecule and every mistake. If the recording process feels like a culmination of the ideas, intentions and feelings you have amassed through the practicing stage, you have done well. If you come away feeling you gave a performance — which in the end is all you can do on a certain day at a certain hour — you have done well. * * *

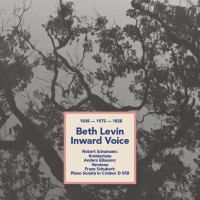

“Inward Voice.” Robert SCHUMANN: Kreisleriana, Op. 16 (1838). Anders ELIASSON: Versione (1973). Franz SCHUBERT: Sonata in C minor, D. 958 (1828). Beth Levin (pno). Aldilà Records ARCD 005 (1 CD) (http://www.aldilarecords.de/). Recorded in Vienna, Austria, in October, 2014. “Personae.” Robert SCHUMANN: Davidsbündlertänze, Op. 6 (1837). Anders ELIASSON: Disegno No. 2 (1987). Frédéric CHOPIN: Sonata No. 2 in B-flat minor, Op. 35 (1839). Beth Levin (pno). Navona Records NV6016 (1 CD) (http://www.navonarecords.com/). Recorded in Brooklyn, NY, in July, 2015. * * * Pictures from top to bottom: The piano at the Ehrensaal der Österreichischen Streitkräfte in der Militärpfarre beim Militärkommando Wien (Vienna); Navona Recording Engineer Peter Karl (Brooklyn); Navona Producer Neil Rynston (Brooklyn); Otto Wagner’s Kirche am Steinhof (Vienna); The Carroll Gardens branch of the Brooklyn Public Library (Brooklyn); Street scene Park Slope (Brooklyn); Aldilà recording team: Ladislav Krajcovic and Jan Machut (Vienna); In the environs of the Münter-Haus, Murnau am Staffelsee (Germany). [Gil Reavill is an author and music enthusiast who lives in Westchester County, New York.]

[More Beth Levin, Gil Reavill]

[Previous Article:

Feldmania]

[Next Article:

Cincinnati Rides Tchaikovsky Warhorses to the Big Apple]

|