Feldman’s SQ2 in Boston

|

Grant Chu Covell [March 2016.]

I first heard about it as the punch line to a joke. A six-hour string quartet? Truly? Then I began to appreciate its outsized composer through recordings. Some pieces were long, and some were very long, spanning multiple CDs. The motivation for a single movement lasting a quarter of a day began to make some sense. The mammoth opus eventually made it to discs (members of the Ives Ensemble on hat[now]ART 4-144 and a different FLUX lineup on mode 112), and I explored those, but across multiple listening sessions. On an unseasonably warm February Sunday (Feb. 28), surrounded by an intent, rapt audience, the gymnastic FLUX Quartet performed Morton Feldman’s Second String Quartet (1983). Advertised as the Boston premiere, the performance was actually across the river in Cambridge, at MIT’s Killian Hall. Part of the MIT Sounding series, sponsoring director Evan Ziporyn warmly encouraged attendees to stretch or step out if needed. Surprisingly few did. There were rubberneckers who wandered in for shorter periods to catch a lingering glimpse of this anomaly, but about 80 of us stuck through to the transcendent end. Feldman’s String Quartet No. 2 is 124 score pages. Each page has three systems, and each system has nine measures. The pulse remains steady throughout, approximately 63-66 quarter notes per minute. However, even though all measures span the same visual width, time signatures vary unpredictably between 1/8 and 11/4. A 5/8 measure may sit between a 4/4 measure and a 2/2 one. Individual measures can repeat two or three times, occasionally more. Sometimes parts of one page will repeat in their entirety much later. Mutes are in place the entire time; dynamics are generally soft. Feldman’s note spelling can be awkward, for instance, using C-flat and B-sharp in the same chord.

That any ensemble can play this is remarkable. Doing anything continuously for near six hours tests human endurance. Tom Chiu, Conrad Harris (violins), Max Mandel (viola) and Felix Fan (cello) moved with efficiency. I didn’t see anyone taking a drink until late in the third hour. The FLUX played from scores and their own cut-ups of score pages. Pages were unbound and had to be shifted from right to left. Players often moved pages for each other, or slid pages while playing open strings. The foursome sat at one end of the hall, but in the round with chairs surrounding. I camped in the third row (or concentric ring) behind the cellist and was close enough to make out the gestures on the cellist’s left-hand page. They started at 2:09 and finished at 7:27 p.m. At 5 hours and 18 minutes, you could say this was a fast reading. Besides the start and finish, I checked the clock just four times (at 2:57, 4:55, 5:39 and 6:34 if you must know). We were a quiet and attentive audience. Many brought things to drink; I only heard food wrappers once. About 40 folks never left their seats, some of us got up to stand at the hall’s perimeter, and several did step out here and there. At least twice, and unfortunately exactly during the ultimate measures, we heard heels clicking as their owner passed through the hallway surrounding the venue.

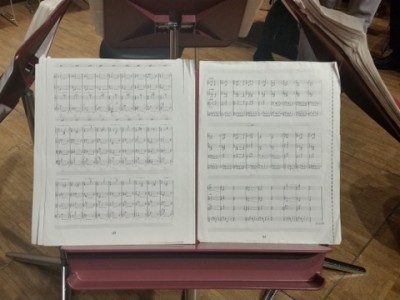

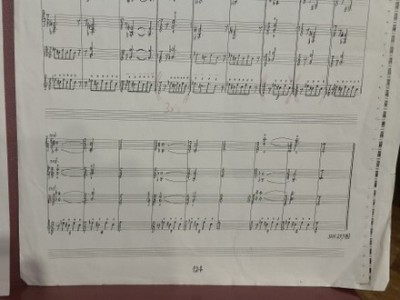

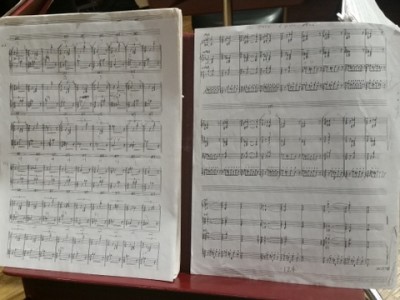

String Quartet No. 2 is the most challenging Feldman there is. There are numerous types of patterns and gestures that may dwell, reconfigure, and reappear the same or slightly modified hours later. Feldman finds many ways to test our memory through reintroducing entire passages, and establishes new moods through gradual and abrupt contrasts. The work’s scale prompts comparison with cyclic events such as weather patterns or an indecipherable Aztec calendar. There are markers reappearing like reassuring cushions: a questioning Webern-like gesture that passes across the quartet, an unexpectedly jazzy pizzicato solo for the cello, and smoothly oscillating harmonics which also appear at the very end. Feldmaniacs might want to skip this paragraph: I don’t think the quartet needs to be as long as it is. The experience of physical discomfort for both players and audience doesn’t necessarily contribute to the musical experience. Some parts are quite beautiful. Some parts are ugly, but still musical and essential. There were several pages in the fourth hour that I wouldn’t have missed. As a strategy to keep alert and reduce fidgeting, I took notes now and again (others were doing the same). I have dozed through entire acts of Wagner, but believe I nodded off only once (somewhere in the third hour). The mind does wander, but snaps to attention when the material changes. Many minutes passed where I wasn’t actively listening, but waiting for the quartet’s texture to change, as if Feldman had composed background radio. Feldman doesn’t just ask you to confront his music: We must also demonstrate inner restraint and accept spending time with oneself. I did cycle through all the things I thought I should have been doing instead on a warm February afternoon, but eventually set them aside to listen. There can be no impatient Feldman fans, and there can be no impatient Feldman players. That the FLUX Quartet has not just played this work, but has recorded it, actively champions and continually presents it is extraordinary and inspiring. [I took pictures of the FLUX’s stands after it was over. The top shows the cellist’s final two score pages, the middle reveals a close-up of the final measures, and the bottom shows the last two customized sheets of the viola’s music.] [Mike has covered both the Ives Ensemble and FLUX Quartet releases, Grant has covered just the FLUX set.]

[More Grant Chu Covell]

[More

Feldman]

[Previous Article:

An American?]

[Next Article:

Soloists Steal Spotlight in Carnegie Hall Concerts]

|