Forgotten Gems

|

[Robert plays tenor sax in the ARC Libre Trio, with Gustavo Aguilar (percussion) and Phil Curtis (guitar and computer). They are currently touring, in a program of Cage, Feldman, Cecil Taylor, Wolff, Tenney, Elaine Barkin, Shaffer, Curtis and free improvising. Ed.] Robert Reigle [April 2002.]

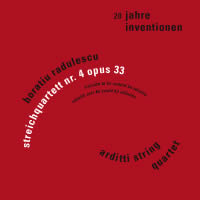

For the largest reference work in existence on music, The New Grove, Second Edition pays remarkably scant attention to the major pathway toward hearing sound in our time: recordings. Articles on composers omit essential discographical data such as what year the music first appeared on a commercial recording, in what order the works were recorded, on what labels, in what countries, by what performers, and in what format. This information provides keys to understanding the development of musical ideas among composers, and their acceptance by audiences (record buyers). I raise this issue in the afterglow of Horatiu Radulescu’s Fourth Quartet, premiered in 1987 and finally reaching my CD player in 2002 (Edition RZ 4002; http://www.edition-rz.de/). I found myself wishing I’d enjoyed this revelatory music over the past fifteen years, and wondering what forgotten gems lie buried in drawers, archives, dusty old trunks, and music libraries. When it comes to very old music, such as the Sumerian notation from 1400 B.C.E., discoveries had to wait decades for translation and interpretation. European Medieval and Renaissance music occasionally reaches the light of day (the aura of sound) through an impossibly circuitous path, such as surviving use as bookbinding or leaving its country of origin through the vicissitudes of war. The 20th century had its own peculiar set of forces, largely economic, impacting the dissemination of music. The changeover from LP to CD led to a blossoming of the record industry, drastically increasing the range of music available on the market, relaxing the pressure on composers and performers to bend their creations toward the public’s ears. We now find ourselves at the opposite end of that cycle, in a slump that makes it difficult to obtain even major-label French recordings, for example. Most listeners have a wish list of music they would like to hear on recordings. My list of composers deserving better representation includes Ambrosini, Barrett, Christou, Dao, Estrada, Finnissy, Gaber, Hambraeus, Ioachimescu, Jolivet, Kelemen, Lachenmann, Marbe, Niculescu, Obukhov, Puig, Reibel, Schöllhorn, Tamba, Uitti, Yuasa, and Zender. In this article I would like to call on record companies to consider a few works that certainly foreshadowed important compositional ideas, and may themselves constitute forgotten gems worthy of a place in our sonic experience. I selected a half-dozen pieces that seem to have the greatest potential for changing the way we view the history of 20th-century music, yet remain unrecorded. György Ligeti wrote his orchestral work Apparitions before the well-known Atmosphères, and the earlier work made an impact that continues to affect composers. So far, radio broadcasts of Apparitions have provided the only sonic access to this groundbreaking composition. The demise of Sony’s complete Ligeti Edition, and now, it seems, a similar fate for Teldec’s series, leaves the biggest gap in the Ligeti discography unfilled more than four decades after its premiere. Another work of mythic proportions, Giacinto Scelsi’s La Naissance du Verbe, received mention at the time of its premiere, by Pierre Boulez in a letter to John Cage (the three had previously dined together). The work marked a culmination that contributed to Scelsi’s nervous breakdown, leading him, after a four-year silence, to develop music that revolutionized the 20th-century landscape. A copy of the score, which Scelsi donated to the Library of Congress, has gone missing. All of Scelsi’s orchestral works have been recorded, some more than once, excepting this massive piece for wordless chorus and orchestra. On a routine visit to Record Surplus in Los Angeles, I discovered a remarkable LP by Josip Slavenski (1896-1955), the leading Yugoslav composer between the World Wars, and the first to make an international reputation. London Records recorded his Sinfonia Orienta (LL-1216, no date), a work for orchestra, chorus and vocal soloists in seven movements: Pagans, Hebrews, Buddhists, Christians, Moslems, Free Thought, and Hymn of Toil! Slavenski wrote for trautoniums, quarter-tones and electronics in the 1930s. An organization has published editions of some of his scores, including Sonata Religiosa, a prescient piece for organ and violin that constitutes, with its full-chromatic sustained clusters, a missing link between Ives and Ligeti. Another quarter-tone pioneer, Ivan Wyschnegradsky, wrote an equally amazing piece in his First String Quartet (1924, revised 1953), wherein a quarter-tone cluster constitutes the tonic or key of the piece. Thankfully, Editions Block and the Arditti Quartet have made this work available on CD. But Wyschnegradsky’s discography is shockingly sparse, given his influence on microtonal music. For example, nobody has recorded Sept variations sur la note DO, for two pianos in quarter-tones, which was premiered in 1945 by Pierre Boulez, Yvonne Loriod, Serge Nigg and Yvette Grimaud at Salle Chopin, Paris. Does that work, written in 1920, foreshadow the one-note and minimalist compositions that began to emerge in the late 1950s? John Foulds wrote a piece in quarter-tones in the 1890s, making him one of the first Europeans to do so since the ancient Greeks. His importance does not, however, lie with the use of quarter-tones as much as in his fusion of Indian and European concepts. He claimed to have received some of his compositions from devas while in a trance, and made arrangements of similarly revealed compositions by his wife Maud MacCarthy (Swami Omananda Puri), an English ethnomusicologist, composer and yogi. Some of his works have appeared on CD, and a comprehensive edition should reveal new insights regarding the integration of Indian and European musical and spiritual ideas, as well as shed light on the milieu that shaped the work of composers such as Gustav Holst, André Jolivet and Giacinto Scelsi. Finally, music that explores the territory between speech and song (including the sophisticated drum languages of Africa, and Chinese music that follows the tonal contours of the spoken language) deserves thoughtful exploration through sound. In a recent article on Arnold Schoenberg’s klangfarbenmelodie, Alfred Cramer notes that in 1930, scientist Richard Paget wrote music that attempted to transcribe the overtones of spoken language (Music Theory Spectrum 24(1): 1-34, 2002). A recording of Paget’s language-music could give new historical depth to the music of David Evan Jones, Charles Dodge, Jean-Claude Risset and Istvan Anhalt, as well as to Schoenberg’s Sprechstimme.

[More Robert Reigle]

[Previous Article:

Singing in the Shower: Ralph Ellison and the Blues]

[Next Article:

On Schumann's Davidsbündlertänze (I)]

|