Golden Oldies: A Century of Singing

|

Dan Davis [September 2009.]

The Record of Singing 1899-1952: The Very Best of Volumes 1-4. Various artists. EMI 28956 (10 CDs) (http://www.emiclassics.com/). Veteran collectors grew up on sandpaper vinyl from obscure labels like OASI (word had it that the letters stood for Old And Scratchy Indeed), developing a preternatural ability to listen through the lethal combination of record noise and primitive recording techniques to focus, laser-like, on the singers of the past, their stylistic idiosyncrasies, and their extraordinary voices. An added bonus was the historical context afforded us — the way each era of singers reflected their own personalities and the performing conventions of their time. Our own rather strait-laced contemporaries value (or overvalue) conveying the notes on the page above more flexible approaches to rhythm, dynamics, and tone color that characterized earlier generations. In the 1970s, EMI embarked on a historic project of releasing four multi-disc LP volumes of the history of singing, from the waning days of the 19th century to the dawn of the LP era. The boxes were lavishly annotated, with plentiful photos and texts and translations of the songs and arias. The exemplary singers were organized by years and by schools of singing — so the French style, Wagnerian styles, bel canto and others were given their full due and listeners could hear for themselves how singers’ approaches changed over time. The present 10-disc set might be called a Reader’s Digest version of those original LP boxes. I no longer have the LP sets but memory and the subtitles of this one (The Very Best Of …) indicate shrinkage of that valuable overview of recorded singing. The lavish notes and texts are, alas, missing, but the CD booklet does give track information that includes recording dates and original matrix numbers. Producer Tony Locarno may well be wearing a bulls-eye target on his back, given the ferocity with which vocal enthusiasts argue about who’s included, who’s left out, and which selections are chosen to represent their artistry. I won’t indulge in that sport here, given the enormous task of limiting the project to 10 discs (the original LP sets came to almost four dozen well-filled discs) and the parameters of choice that led to excluding better known items likely to be in the collections of seasoned fans. Classic singers and their most representative recordings have been well served by such labels as Naxos Historical, Nimbus, and EMI itself in more easily digestible chunks. While I regret that the full LP sets haven’t made it to CD intact, this is a significant project worthy of enthusiastic support, not least because many items have been remastered with needed pitch corrections, and because releasing a monster set like this in the midst of an ugly recession is a gutsy move that demands respect. The word “ugly” reminds me that the set opens with a recording of the last of the castrato singers of the 19th century, the then-elderly Alessandro Moreschi, recorded in the Sistine Chapel in 1904. He’s there as a historical artifact, not for singing that’s painful to listen to as he croaks his way through Gounod’s soupy Ave Maria. But after that, we get the gold medalists: From the legendary Adelina Patti on Disc One to Zinka Milanov on the last track of Disc Ten there’s a procession of great singers and great artistry. Even singing buffs like myself will be reminded of names ordinary mortals will have forgotten, like Rosina Storchio and Gilda dalla Rizza. But the big names still rule supreme, even in a set of highlights. Caruso, of course, but also selections of extraordinary Russian tenors like Leonid Sobinov and Dmitri Smirnov, basses ranging from lords of the bottom octave like Lev Sibiriakov and elegant French basses like Pol Plançon. I was delighted to see personal favorites included — Hermann Jadlowker’s stunning 1912 version of an aria from Mozart’s Idomeneo and Alessandro Bonci’s 1905 Gluck aria. In general, the earlier recordings favor the men: The primitive acoustic horn process removed the overtones from the high notes of sopranos and mezzos, sometimes even stripping hints of such vibrato as may have been employed. Male voices, with their lower range, have a presence on those ancient 78s that preserves more of their timbre. And there’s the matter of the surface noise, artfully suppressed in most of the pre-LP items here, but something that may disturb newcomers to vintage recordings, especially those who grew up with the squeaky clean but lifeless sound of early digital. That said, most of the later recordings, from the 1920s onward, are more than adequate. It would have been wonderful if EMI had simply duplicated the contents of the original LP boxes (remastered, of course) but what they have given us here will have to do for now. It’s a cornucopia of vocal delights at budget price, a handy box for collectors who’ll have much of it anyway, and a source of discovery and delight for newcomers to the treasures of old.

The Record of Singing 1953-2007: Volume 5. Various artists. EMI 28949 (10 CDs) (http://www.emiclassics.com/). Volume 5 of The Record of Singing brings the narrative up to date, from the LP era to today’s digital one. If my welcome for this 10-disc volume is less enthusiastic than for its predecessor that’s not due to a falloff in the quality of modern-day singers but to certain structural limitations along with those of personal taste. The biggest problem here lies in copyright laws that virtually guarantee such compilations will be limited to recordings owned by the issuing company; the alternative being licensing fees that would make the project economically unfeasible. So what we really have in Volume 5 is The Record of Singing by EMI Artists. That isn’t so shabby in itself, since EMI has always been a major player in complete opera recordings and recitals. But it is a powerful limitation. After all, a comprehensive overview of post-1953 singing without Renée Fleming, Ivan Kozlovsky, Pavel Lisitsian, Zara Dolukhanova, and René Pape, among many others, is seriously flawed. Another problem lies in applying those restrictions to a 10-disc survey, which means a lot of “filler” material that replaces the big guns with … well … water pistols. Not to be unfair, but who would suggest that a selection by tenor Ronald Dowd belongs between arias by Fritz Wunderlich and Alfredo Kraus? Or that Wilfred Brown shares a disc with Franco Corelli and Nicolai Gedda? No point in belaboring this or in citing the many other examples that exhibit the same lack of proportionality. A section titled “Singers of the New Millennium 2001-2007” also has established stars rubbing alongside newcomers whose chief claim to fame is that EMI owns their recordings. A final bit of carping is a purely personal one, which you can take as my own failing of taste, knowledge, and hopeless inability to keep up with the latest trends: There are too many tracks devoted to countertenors. Yes, the revival of Baroque opera has led to a newfound popularity of this voice category, and there are some fine singers documented here. But there is a run of tracks on Disc Nine that preserves many of those sadly anorexic, hooting voices that were once foisted upon us in the perversely mistaken belief that they represented “authenticity” when they only represented horrendous squawks that would shame a crow. So after all this complaining, why do I still recommend this set? First, it looks good on a shelf alongside its companion set. Second, at budget price, you can skip the below-par tracks and still have an abundance of fabulous singing by the top artists of our era — fantastic Wagner by Astrid Varnay and Hans Hotter, and such indisputably defining artists of the half-century like Jon Vickers, Maria Callas, and Montserrat Caballé. Finally, you may disagree with me and love every last track on every disc, all the while muttering about how reviewers are always finding things to moan about.

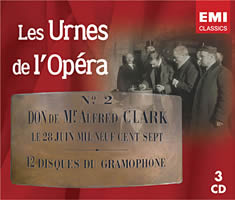

Les Urnes de l’Opéra. Various artists. EMI 206267 (3 CDs) (http://www.emiclassics.com/). This compilation comes from EMI’s French branch, with a booklet in French to seal the deal, and it’s another compilation of the major artists of the early years of recording. It comes with a compelling back-story. For this set consists of the contents of three sealed urns stashed in the bowels of the Paris Opera’s basement in 1907 — 78 rpm records of artists considered the greatest of their era. They were a “time capsule” to be opened 100 years later so that future generations could hear the most important artists of the period captured in the revolutionary new technology of recordings. Today that technology has evolved to the point where those early acoustic 78s seem hopelessly primitive, although I’ll hasten to say that the restoration work renders this set eminently listenable. The dignitaries at the entombment ceremonies couldn’t have imagined that these samples of work by Caruso, Patti, Melba and others would be quite familiar to vocal buffs of the 21st century but that hardly diminishes the appeal of this set, for there’s a hefty dose of singers whose fame has faded over the years, yet whose artistry has not. Of special interest are the French singers then popular at the Paris Opera. At a time when the international style has virtually obliterated specifically national singing styles (even today’s French singers no longer include nasality in their vocal arsenal) it’s fascinating to hear singers like Léon Beyle, Léon Campagnola, Pol Plançon and Lucette Korsoff, among many others. And if you want to hear the orotund declamatory French of the past at its most irresistible, the actor and director Firmin Gémier’s spoken introduction to the contents of the “time capsule” almost steals the show from Caruso, Tettrazzini, and the other famed headliners whose records were placed in trust for posterity. They’re not all singers, by the way. Included, too, are instrumentalists like the young Fritz Kreisler, Ignaz Paderewski and even, believe it or not, the Coldstream Guards and the Garde Républicaine.

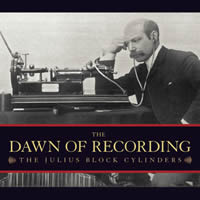

The Dawn of Recording: The Julius Block Cylinders. Various artists. Marston 53011 (3 CDs) (http://www.marstonrecords.com/). If you’ve read this far you’re probably a confirmed maven of historical recordings and/or vocalists. In which case you’re familiar with the work of transfer expert Ward Marston, who has an uncanny knack for turning the unlistenable into the enjoyable, coaxing from the grooves of noisy cylinders and ancient 78s subtleties of sound and presence one never expected to hear. The present release, though, is more like the pre-history of recording rather than its dawn, and Marston in his booklet article readily admits that even the best of the cylinders are sonically primitive. But, he writes, “through the heavy blanket of noise, one can feel a palpable spontaneity rarely captured on early commercial recordings.” The back story to this set is even more fascinating than those dusty urns of the Paris Opera. Julius Block was a businessman who brought Thomas Edison’s cylinder recording machine to Russia in 1889, demonstrating it to, among others, Tsar Alexander III and to the country’s social and musical elite in a series of soirees, snippets of which he recorded. The results included spoken tracks by Tolstoy and Tchaikovsky, musical excerpts played by Taneyev, Conus, Arensky, and the young Josef Hofmann, and star singers of the St. Petersburg Opera. In 1899 Block moved to Germany, where he continued to hold his recording soirees. Disc Two includes several selections played by the 11-year-old wunderkind, Jascha Heifetz, days after his sensational debut with Nikisch and the Berlin Philharmonic. There’s also about 24 minutes of virtuoso violin works played by the 19-year-old Eddy Brown, like Heifetz a pupil of Leopold Auer, but one who made few commercial recordings despite being hailed as one of America’s finest violinists. Block died in Switzerland in 1934 and it was believed that his collection of cylinders was destroyed during World War II. Some were, but the bulk of his Berlin Archive eventually wound up in Pushkin House, a literary institute in Leningrad, now once again St. Petersburg. The set’s booklet, as in all Marston releases, includes extensive essays, pictures and biographical notes on the artists included, along with Marston’s own article on the discovery of the cylinders and the challenges they presented in transferring these primitive recordings to the digital realm. He’s frank in discussing the parlous state of the originals and the necessarily sub-par sonics of the resulting discs. Listening, he writes, “may take some effort, but the rewards are worth the trouble.” Those rewards include insights into the performing practices of a bygone era and the first, often the only, recorded examples of important musicians who otherwise would only be names in music history books. Admittedly, this set’s primary appeal will be to antiquarians and those who have the experience and the desire to listen through the fog of noise to extract the faint sounds of the past. My own attempts at doing this were only intermittently successful but that doesn’t dim the importance of this set, which has the historic value and curiosity factor to attract collectors. If The Dawn of Recording tickles your interest it can be acquired directly from Marston’s website: http://www.marstonrecords.com/. If you’re interested in historical performers but prefer expertly transferred recordings with better sonics than these early cylinders, a visit to Marston’s website is mandatory. Upcoming releases include another volume in their invaluable Josef Hofmann series, a new series on historical excerpts from Meyerbeer operas, and more. Marston presses only 1,000 copies of each release and doesn’t repress, in effect creating collectors’ editions of materials not available elsewhere.

[More Dan Davis]

[Previous Article:

Solos and Underdogs]

[Next Article:

Album Tweets 2.]

|