Haydn Year Highlights 1.

|

Dan Davis [November 2009.] The 200th anniversary of Haydn’s death has led predictably to an abundance of new releases and reissues of his music. I can’t pretend to have heard more than a reasonable portion of them, but without attempting a comprehensive assessment of the year’s bounty, allow me to share my enthusiasm for the most interesting of the 2009 releases I’ve heard. Part 1 includes larger-scaled works. Coming soon, Part 2, chamber and solo pieces.

Franz Joseph HAYDN: Symphonies Nos. 82-88; 93-104; The Creation; Masses. New York Philharmonic, London Symphony, various soloists and choruses, Leonard Bernstein (cond.). Sony 748045 (12 CDs) (http://www.sonymasterworks.com/). Let’s begin with Lenny — always a good idea. Sony’s repackaged all of Bernstein’s Columbia Haydn recordings into one neat budget-priced box crammed with excellent performances of the late symphonies and choral works, making this an essential reissue. Bernstein was a great Mahler conductor in part because he was so attuned to Mahler’s angst, but he was a great Haydn conductor because he was in sync with the rapier wit, bold strokes, and endlessly imaginative components of Haydn’s writing. We can hear that affinity at work in the “Paris” symphonies 82-87, where Bernstein’s outer movements are full of vitality, the slow ones overlaid with emotional depth. Those qualities are also present in the late “London” symphonies, the Masses, and the oratorio The Creation, along with Bernstein’s gift for projecting rhythmic life without marring Classical proportions. That this is big-band Haydn goes without saying. The recordings were made between 1959 and 1979; the symphonies, between 1959 and 1970. There’s less of the traditional elegant charm; more of the New World’s thrusting energy and steely strength, elements slightly exaggerated by the aggressive sonics of the originals. The choral works have that same larger-than-life intensity, featuring the expressive singing and playing that make these works so powerful. All in all, with its occasional faults, this box is a must. If you already have these issues, then be a sport and put it on your Christmas gift list for those near and dear who’ll appreciate the stellar combination of Haydn and Bernstein.

Franz Joseph HAYDN: Symphonies Nos. 93-98. The Cleveland Orchestra, George Szell (cond.). Sony 748904 (2 CDs) (http://www.sonymasterworks.com/). Yes, George is scowling on the cover of this stellar reissue, probably trying to capture his public image as a cold customer. But there’s nothing cold about his Haydn performances — they’re characterized by precise orchestral execution and structural logic, but full of excitement, humor and yes, warmth as well. Where Lenny’s Adagio opening of No.98 is ominous and dramatic, Szell’s has more mystery, with inner lines emerging to maximum effect. In the last movement, Bernstein’s humor is more explicit; he’s trying to get a belly laugh while Szell’s (and Haydn’s?) approach is more smile-inducing, the mindless dance melody disrupted, even subverted, by pauses. On the other hand, Bernstein’s Adagio cantabile movement is less lean, the strings lush, the pace slower than Szell’s more graceful reading. Such observations can be applied to the other symphonies — Bernstein more explicit, Szell more subtle. But don’t confuse subtlety with understatement; the belching bassoon in No. 93 and the rollicking surprise of No. 94 grandly qualify as broad humor, proving that Szell was not immune to Haydn’s version of slapstick. I recall the Epic LP originals of these recordings as flawed, with piercing violin sound and muddled lower strings. But these discs are far superior, with admirably delineated details and wider dynamics, along with more natural sound that raises the temperature of the performances, considerably reducing the Szellian “chill factor.”

Franz Joseph HAYDN: Die Jahreszeiten. Soloists, Arnold Schoenberg Choir, Concentus Musicus Wien, Nikolaus Harnoncourt (cond.). Deutsche Harmonia Mundi 28126 (2 CDs) (http://www.sonymasterworks.com/). The Seasons is usually classified as a secular oratorio, in contrast to the more overtly religious frame of The Creation. But the best parts of the work are clearly those deeply felt sections where Haydn sets texts praising God for the freshness of spring, the bounty of harvests and, at the conclusion, reflections on the transitory nature of life and the glories of Heaven. It is in such moments that we hear Haydn’s music rise above the work’s genre, if not enough to alter the general consensus that The Creation, which preceded it, is far superior. I’ll buy that view too, though there’s so much worth hearing in The Seasons — the languid opening of Summer, the chorus hailing the sun, the hunting chorus with its baying hounds and horns, and the sections of praise mentioned above. There are also bucolic, rustic scenes where Haydn demonstrates his onomatopoeic gifts with teeming orchestral details depicting everything from frogs croaking to powerful thunderstorms. The text isn’t the best, and unless you’re a devotee of peasant humor and rural hi-jinks, the music nods at times. But the good outweighs the less good in this work when the performance carries with it the conviction displayed here by Harnoncourt and his crew. The soloists are especially worth hearing. Soprano Genia Kühmeier is well suited to her part, conveying the torpor of a hot summer day in her aria and doing the perky peasant lass bit elsewhere, but it’s the men who take the crown, for they are two singers who are, in my estimation, the best of the current crop of lieder singers. They’re also possessed of voices big and colorful enough to score points in a large-scale oratorio like The Seasons. Werner Güra’s tenor is a beautiful instrument used with verbal acuity and baritone Christian Gerhaher, another outstanding Schubert singer, matches him. Both employ a wide range of tonal color, and when Gerhaher drains the color from his voice for the bleak allegorical aria of human futility, he sends a properly wintry chill through you. Harnoncourt’s reading is full of affection, and while he can’t completely avoid a touch of the soporific in Summer’s depiction of lethargy, his overall pacing has the feel of inevitability and he brings clarity to Haydn’s complex fugues. He’s also to be credited with the splendid playing of his period-instrument orchestra and the full-bodied singing of the outstanding chorus, all the more impressive for this being a live concert recording.

Franz Joseph HAYDN: The Creation. Soloists, RIAS Chamber Choir, Freiburg Baroque Orchestra, René Jacobs (cond.). Harmonia Mundi HMC 992039.40 (2CDs, 1 DVD) (http://www.harmoniamundi.com/). Jacobs is one of the few conductors who’s always interesting to hear; his recordings are reliably endowed with dramatic flair and interpretive insights, and he has a marked affinity for Classical-era composers. His 2004 recording of The Seasons (reissued in 2008 as Harmonia Mundi HMX 2961829) is one of the best available and it’s a viable, even preferable, alternative to the new Harnoncourt. But while there’s much to admire here, there are some aspects of the performance that disappointed me, although they didn’t stop me from enjoying multiple auditions of the set or finding the accompanying “Making of …” DVD a welcome bonus. To get the complaints out of the way: They mainly center on orchestral execution. The Freiburg band’s strings often sound sour, as if they haven’t received the message that period instruments can be played without inflicting pain, and the gaunt ensemble sound reduces the impact of this large-scale work. A quick reality check with the Bernstein is telling. Two examples: Bernstein’s representation of Chaos is vividly dramatic, Jacobs’ ill-defined and ill-played; and in Haydn’s extraordinary depiction of the rising sun, the famously resplendent D Major comes off as merely abrasive in the Jacobs set. Jacobs does get the band to play with gusto in Haydn’s vivid depictions of the creatures of the air, land and sea — you can almost see the spinning birds, slithering snakes and slow-moving whales. And the RIAS chorus is first-rate, their color tints and articulation exemplary. So too, are the soloists. Soprano Julia Kleiter is an outstanding Eve, Maximilian Schmitt’s tenor has both lyricism and muscle, and Johannes Weisser’s bass has the requisite depth and understanding. Jacobs’ pacing is on target, full of verve in the dramatic sections, and flowing in the lyric ones. Add good, clear sonics and you have a Creation eminently worth hearing. Too bad about those violins, though.

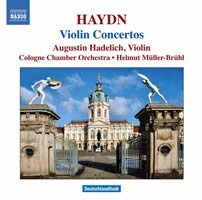

Franz Joseph HAYDN: Violin Concertos Nos. 1, 3, 4. Augustin Hadelich (vln), Cologne Chamber Orchestra, Helmut Müller-Brühl (cond.). Naxos 8.570483 (http://www.naxos.com/). Haydn didn’t write many concertos relative to other genres, and of the nine once attributed to him, only four were genuine and of those, one is lost. The three on this disc, then, constitute his available violin concerto output, written as showcases for the virtuoso principal violinist of Haydn’s orchestra at the Esterházy court, Luigi Tomasini. I don’t know how Tomasini measured up to the works’ demands but Hadelich certainly does. He’s terrific in their showy sections, with all the flash and fireworks you’d want in the double-stopping and ornamental figurations. But he also excels in slow movements; the violin’s song in the exquisite Adagio of Concerto No.1 is suffused with intense feeling and tonal sweetness. Müller-Brühl and his modern-instrument Cologne Chamber Orchestra offer stylish support and the engineering is admirably transparent. These may be early works but they’re gorgeous ones I play often without diminished enjoyment. In fact, I’ve played them so often in 2009 that I’ll break my self-imposed parameter of only 2009 releases to include this 2008 release — when such a marvelous disc comes along, what do a few months matter?

[More Dan Davis]

[More

Haydn]

[Previous Article:

Plus de Musique de Chambre]

[Next Article:

Haydn Year Highlights 2.]

|