Holst Seven, Matthews Nil

|

Ethelbert Nevin [September 2006.]

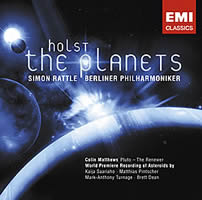

Gustav HOLST: The Planets, Op. 32 (1914-16); Colin MATTHEWS: Pluto, the Renewer (2000); Kaija SAARIAHO: Asteroid 4179: Toutatis (2005); Matthias PINTSCHER: towards Osiris (2005); Mark-Anthony TURNAGE: Ceres (2005); Brett DEAN: Komarov’s Fall (2006). Berliner Philharmoniker, Rundfunkchor Berlin, Simon Rattle (cond.). EMI 0946 3 59382 2 7 (http://www.emiclassics.com/). 2CDs, second contains video: “The Making of The Planets and Asteroids.” The last time a living composer’s comments raised hackles (the only time perhaps?), that German gent, the one who’s working at a seven-day opera, uttered some “misconstrued” words about 9/11. Colin Matthews, thanks be, has kept his council with respect to word arriving from Prague about Pluto’s less-than-planetary status. (Matthews is the British composer who assisted Deryck Cooke on an edition of Mahler’s Tenth.) Musicians aren’t ordinarily asked to weigh in on astrophysics; however, in 2000, Matthews composed Pluto, the Renewer, a symphonic movement intended to cap Holst’s seven-movement Planets, the elder composer having completed his work before Pluto’s discovery. With commendable prescience, Matthews’ notes for the premiere acknowledge flaws in Pluto’s membership, and today he seems genuinely delighted by all the fuss. As Matthews basks in the limelight, EMI is probably seeing green. The label just released The Planets and Pluto from recordings made earlier this year by the Berlin Philharmonic under Simon Rattle — oops, Sir Simon Rattle. Not only do we get Matthews’ add-on, we’re treated to four bonus asteroids! Well, actually, one of the asteroids was also just reclassified: Ceres joins Pluto in the “dwarf planet” category. Damn the specifics, full speed ahead! I grabbed the twofer, with its how-we-made-the-video on the second, enhanced CD, because I really wanted to hear the new works. According to EMI, Holst’s Planets is “the most frequently performed piece of British 20th-century classical music.” More popular than Elgar’s Enigma or the first Pomp and Circumstance march? Well, never mind. These Elgar compositions are essentially 19th-century works, and there’s no arguing that The Planets are fodder for film-music composers. John Williams ought to assign one of his Star Wars Grammies to the Holst estate, which did in fact move against Hans Zimmer for his Gladiator score. Astrologists will note that Holst’s suite contains only seven movements. Evidently Earth held no significance in his mystical scheme of things. Those of us now struggling to devise mnemonics for the remaining heavenly orbs will have remarked Holst’s having swapped Mercury and Mars. Just as Strauss’ Also Sprach Zarathustra never quite surpasses its opening, The Planets struggles to overcome its brilliant, martial start. Mars isn’t just the suite’s calling card, it’s Holst’s famous moment in music. Other than Beethoven (Fifth Symphony) and Ravel (Boléro), few composers have become famous for rhythms. Alongside Brubeck’s Take Five, “Mars” is an oft-cited example of a 5/4 meter. Poor Holst. He loathed the recognition The Planets brought and never wrote anything like it again. Few musicians can name another Holst piece, except maybe the St. Paul’s Suite for string orchestra and perhaps one or two choral works. Mars’ rat-a-tat-tat does have its attractions, especially the way Holst alternates the lumbering gait to create forward motion. My favorite cut is “Jupiter, the bringer of jollity,” with its unending melody tucked in the center. Here in America we’re unaware of its dual life as the patriotic hymn, “I vow to thee, my country.” Holst was inspired by Schoenberg’s Op. 16, and sought to replicate some of its large orchestral effects in his suite (subtitled “Seven Pieces for Large Orchestra”). Col legno bowing was rarely used in Britain before Holst employed it at Mars’ start, but the cleverest effect comes at Neptune’s end where he instructs the offstage chorus to be quieted as if a door gradually closes them out (which a number of listeners would probably like to see installed as a permanent option for every piece). As if compensating for the non-planet’s eccentric orbit, Matthews’ Pluto can follow Neptune without a break, beginning and ending with its predecessor’s ultimate chord. Brisker than Mercury, there are fleeting allusions to the other planets. It sounds modern and yet grounded in Holst’s idiom. Saariaho’s asteroid is the shortest and most pragmatic. The notes mention how Toutatis’ motion follows two independent periods of 5.4 and 7.3 Earth days, ratios which must be embedded within the work. Pintscher’s towards Osiris, the longest by just a matter of seconds, is the most spirited and perhaps the most unnecessarily showy. Apparently this represents a sketch for a larger effort to be premiered in 2008 with the Chicagoans and Boulez. For a few days in August it looked as if Turnage was about to score big, having written a piece named for a planet-to-be. Actually, he has an asteroid-suite business going himself, with a Juno and Torino scale for the Bamberg Symphony already in the bag. Dean’s Komarov’s Fall has a plot, unlike the others, which are mostly descriptive. Named for Cosmonaut Vladimir Komarov who perished on Soyuz I’s reentry, the work imitates “space telemetry signals,” Komarov’s frantic conversations with mission control, and his wife’s farewell. With rhythm and flow underpinning his suite, Holst’s music is well-suited for the ballet. The elder stood in awe of the heavens; the youngsters after something rather more terrestrial. Their works encapsulate multiple contrasts in short periods, presumably in an effort to distinguish themselves from the competition. (Were these originally programmed together or separately?) Rattle and the Berliners behave acceptably. This is a solidly performed Planets, and yet the production wants for sparks. Listeners expecting Karajan’s bravado or Boult’s sophistication will be disappointed. EMI’s sonics are unacceptably dull, though not, on balance, as a detriment to the five new pieces. The Holst-plus-Matthews more coarsely textured and livelier eight on Naxos 8.555776, with David Lloyd-Jones leading the Royal Scottish National Orchestra, opt for a tweaked Neptune, permitting Pluto to follow attacca, as does The Hallé Orchestra’s “world premiere recording” (Hyperion CDA67270) with Mark Elder conducting. At 6:53, Lloyd-Jones’ Pluto is slightly slower than Rattle’s 6:12; Elder’s duration is 6:22, with Jupiter’s hymn breezing by on the express track. I’m happy to have the new pieces, especially the Saariaho. This set will sit on my shelves next to an anomalous partner: Gardiner’s DG 445 860-2, which I’ve retained for the filler, Grainger’s luxuriant The Warriors.

[More Ethelbert Nevin]

[Previous Article:

Sticking with col legno]

[Next Article:

New and Essential Xenakis, Part 1]

|