Italian Vacation 1.

|

Grant Chu Covell [July 2003.] If I could vacation anywhere in the world, I’d pick Italy: the food, the art and culture, even the inconsistent trains and crazy drivers. There’s a slim chance I’ll get there later this summer. But it’s time now to indulge in some armchair listening, and I’ve been soaking up new releases of 20th-century Italian music, wonderful discoveries among them.

Luigi NONO: Variazioni canoniche sulla serie dell’ op. 41 di Arnold Schönberg (1950); Varianti (1957); No hay caminos, hay que caminar Andrej Tarkowskij (1987); Incontri (1955). Mark Kaplan (violin); Sinfonieorchester Basel, Mario Venzago (cond.). col legno WWE 1CD 31822 (http://www.col-legno.de/). Distributed in the US by Qualiton (http://www.qualiton.com/). Claudio Abbado, recalling his collaborations with Luigi Nono, remarked how performing a Nono piece in a new space was like playing the work for the first time. More than any other 20th-century composer — and like the Gabrielis, the other great Venetian composers centuries before him — Nono wrote music sensitive to the performance space’s acoustics. No hay caminos, hay que caminar Andrej Tarkowskij will sound drastically different in a cathedral or a train station, for which differences conductors compensate by stretching tempos and moving players. Not surprisingly, no two recordings ever sound the same. On this col legno release, Mario Venzago and the Sinfonieorchester Basel provide four convincing performances; two are startling when compared with other recordings. The Variazioni canoniche sulla serie dell’ op. 41 di Arnold Schönberg is Nono’s Op. 1. After completing courses in law, Nono studied with Bruno Maderna, devouring everything he could about serialism and Renaissance polyphony. The result is the four-section Variazioni canoniche, a mighty knot of intricate puzzle canons and serial technique for orchestra enhanced with piano, saxophone and percussion. The work premiered in 1950 at the Darmstadt Ferienkurse für neue Musik, and Nono’s career was made. (Henze’s Second Symphony was on the same program.) Compared to other works from the “Darmstadt school” (it was Nono who gave a name to the bleeding edge of postwar compositional thought that included Boulez and Stockhausen), Nono’s music is more passionate and expressive. (Boulez completed his Second Piano Sonata in 1950 and Stockhausen was just embarking upon his Op. 1, Kreuzspiel.) Nono didn’t strut his stuff with any old Schoenberg row. Op. 41 is Schoenberg’s Ode to Napoleon Buonaparte, a setting of Byron with an anti-totalitarian message. From the beginning, Nono welded politics with music. But how do you construct canonic variations on twelve pitches? Schoenberg’s original row can be broken into two groups of six pitches, three groups of four pitches, and four groups of three pitches. Nono fragments the pitch groups across the orchestra as did Webern in his Concerto, but he uses octave doubling, trills and complex rhythms. The texture is transparent and successive notes from any instrument are rare (there is an exceptional saxophone solo towards the end). The music searches for something that will never be found. Three decades later, Nono admitted he had forgotten some of the puzzle canon techniques he used to forge the work. If you know Michael Gielen’s recording with the Sinfonieorchester des Südwestfunks on Naïve Montaigne MO 782132, Venzago’s slower tempos feel like walking underwater. (Gielen clocks in at 20:07 while Venzago takes 25:48.) It’s initially infuriating, but one is obliged to take Venzago’s interpretation seriously. A new richness and tenderness alternates with brittle and robust gestures. At the 8:14 point in the Venzago, a magical piano and timpani passage rings clear compared with Gielen’s blurring of this passage. Incontri is a short and vigorous piece for 24 instruments. It’s easy to miss that the work is an exact palindrome. Even with a stopwatch and close listening, you’ll be hard put to locate the spot where the music turns back upon itself. Varianti is something like a violin concerto, and this is one of its most recent recordings. Like Variazioni canoniche, it too flows slowly. The string orchestra dominates the accompaniment whose precisely specified combinations of sul ponticello, pizzicato and col legno rarely appear more than once. It’s easy to overlook the infrequently appearing winds. Nono later drew upon the solo part of Varianti in his late masterpiece for solo violin and tapes, La lontananza nostalgica utopica futura. Here violinist Mark Kaplan leaps and cavorts, and the close recording instills flesh and blood (breathing and shuffling) into this atmospheric composition. Oddly, there is no place for the soloist’s ego. His is a difficult and virtuosic part with neither cadenza nor spotlight. No hay caminos, hay que caminar Andrej Tarkowskij is a magical work for seven groups of instruments distributed around the audience. Sounds, timbres and pitches operate like blocks stacked, stretched, compressed and reordered as if a mobile. Most of the piece is slow and quiet (ppppp) with arresting explosions (fffff). The mention of Tarkovsky may repel those who know the Russian director’s slow-moving, exceptionally controlled films. Indeed there is a similarity in Nono’s homage to an artist whose work he respected. No hay caminos makes brilliant use of instrument ranges and microtonality. You can listen to the work several times without realizing that the entire composition uses but one pitch — G — in six precisely notated degrees of microtonal inflection. Colors connect to specific registers: The highest G is played by violins and piccolo, the lowest by brass. Nono creates ingenious combinations of colors and registers: Occasionally the double basses emit a microtonal wail as they play a G at the top of their range. As for timings, Abbado’s version with the Ensemble Anton Webern on DG 437 840-2 looks fast on paper at 16:51 but doesn’t feel fast. Gielen on Naïve takes 24:00. Venzago runs the longest at 25:45. How can the same piece vary so wildly? Abbado’s live performance is in a less resonant space and so the piece has to move faster. Gielen and the Sinfonieorchester des Südwestfunks played in a train station (there’s a photo). The strange venue is extremely resonant. Venzago’s venue is a concrete hall, the Goetheanum in Dornach (http://www.goetheanum.ch/). Enthusiastically recommended. Nono fans will find a lot to think about. Newcomers have a fine opportunity to form their own opinion of Nono with the help of these exemplary performances of important pieces.

“Sofferte Onde Serene.” Giacinto SCELSI: Quattro Illustrazioni (1953); Suite No. 10, “Ka” (1954). Luciano BERIO: Cinque Variazioni (1953); Sequenza IV (1966); Brin (1990); Rounds (1963). Luigi NONO: Sofferte onde serene (1976). Kenneth Karlsson (piano). Albedo ALBCD 015 (http://www.albedo.musiconline.no/). Transcribed from improvisations, the Quattro Illustrazioni are among Scelsi’s more frequently performed and accessible works. Each movement describes one of Vishnu’s metamorphoses: sleeping (No. 1), as animal (No. 2), as the perfect human (No. 3), and as God (No. 4). In the second illustration, where Vishnu is an angry boar running across the countryside, the music is Prokofiev-like: vigorous and violent. Other pianists use this movement as an excuse to go over the top, push the pedal to the floor, and bang out octaves (Werner Bärtschi on ECM 1377 and to a lesser extent Suzanne Fournier on Accord 200742). Karlsson maintains a wondrous level of restraint while at the same time conveying the piece’s brutality. Suite No. 10, “Ka,” consists of seven short movements, also derived from improvisations. Scelsi said “Ka” has various meanings, of which “essence” is its most important. While the Quattro Illustrazioni are pictorial, Suite No. 10 is abstract, with the movements dwelling upon a particular figure or a narrow range of expression. Many repeated notes, trills and short figures appear in this suite, with curving, modal melodies appearing between the blunt statements. With Karlsson, I finally get Berio’s Sequenza IV. Other performances, such as Florent Boffard’s in DG’s set of Sequenzas (DG 457 038-2, 3 CDs) or David Arden’s pass at all of Berio’s piano music (New Albion NA 089 CD), don’t articulate the difference between the razor-sharp staccato chords and the wispy filigree that runs around them. For the first time, I clearly hear two distinct types of activity that Berio folds together and then separates. I also hear a connection with the 1974 orchestral piece Eindrücke (Erato 2292-45228-2), which now sounds to me like an elaboration of this very work. The other Berio pieces are less demanding. The Cinque Variazioni is contemporaneous with the two Scelsi works but a truer exemplar of its time. (Scelsi worked in a vacuum until he was “discovered” in his last decade. Quattro Illustrazioni was not premiered until 1977.) Brin is a two-pager from Berio’s collection of six encores. Rounds is an explicitly notated version of a work that started as a graphic score. (Berio has “fixed” several of his graphic works, most notably Sequenza I for flute.) Where Arden flies through these works, perhaps recklessly, Karlsson is more casual and considered. Sofferte onde serene is a great Nono work. Inspired by the church bells of his native Venice, it combines piano with a mono tape of Maurizio Pollini’s piano sounds. The work marks the passing of several of Nono and Pollini’s family members. In a performance, the tape is broadcast from a speaker placed under the piano. The music is brutal and beautiful, with the pianist hammering out awkward chords and at the same time precisely notated rhythmic clusters. The classic recording of Sofferte onde serene (actual title sofferte onde serene ) is Pollini’s from 1977, reissued in the Maurizio Pollini Edition singly on DG 471 362-2. Markus Hinterhäuser, assisted by longtime Nono collaborator André Richard, is relatively sterile (col legno WWE 1CD 31871) and no challenge. However, the DG’s taped aspect sounds rather more distant. With Karlsson, the prominent tape details are more audible, yet the tape exhibits its antique qualities by overloading in several places. Karlsson’s is also a live performance. Audience noise and what sounds like the fluttering of pigeon wings fit perfectly. Karlsson plays passionately and cleanly with a light touch and restrained pedal, especially noticeable in Sequenza IV where the sustain pedal carries several notes forward. The intimate recording has Karlsson’s breathing humanizing the Scelsi. I look forward to hearing more from him and Albedo.

“The Scelsi Edition, Volume 3: Music for High Winds.” Giacinto SCELSI: Ixor (1956); Suite (1953); Preghiera per un’ ombra (1954); Ko-Lho (1966); Pwyll (1954); Tre pezzi (1954); Rucke di Guck (1957); Three Latin Prayers (1970). Carol Robinson (clarinets); Clara Novakova (flute, piccolo); Cathy Milliken (oboe). Mode 102 (http://www.mode.com/). Mode’s third volume of Scelsi focuses on chamber music for clarinet, flute and oboe, definitive performances all. Clarinetist Carol Robinson, who worked with Scelsi in the 1980s, is the major force behind this recording. A special treat for Scelsi fanatics is the inclusion of a photo of the Roman forum taken from the oddball composer’s apartment. I especially enjoy this recording’s immediacy. The Suite’s flute and clarinet will be there in your living room. This surprisingly conventional duet has the flute and clarinet frolicking together like bubbles in a fountain. The opening hints at something bucolic, even Mahlerian (think Third Symphony). Bounding ahead 13 years to another flute and clarinet duet, Ko-Lho, Robinson and flutist Novakova play as one, with teasing and insistent microtones, flutter-tonguing, multiphonics, and passionate phrasing. These two duets alone demonstrate Scelsi’s variety: the expressive, traditional melodist vs. the avant-garde sculptor of single-tone music emphasizing timbre and color. Flute alone revels in Pwyll, a short, acrobatic piece. Some of Scelsi’s titles, such as Ko-Lho, are pure inventions, but there is a Pwyll in Celtic mythology. Scelsi’s Pwyll revolves around several pitches and a limited set of modal harmonies. Rucke di Guck, the third duet, a raucous and busy set of three emphasizing the instruments’ shrill and piercing qualities, is scored for piccolo and oboe. If I remember correctly, “rucke di guck” is a taunting refrain sung by birds in a Brothers Grimm fairy tale. There are four works for solo clarinet: Ixor, a tiny gestural invocation that bounces out of a few repeated notes; Preghiera per un’ ombra, a cry of suffering and rage at the death of a loved one; the virtuosic Three Pieces for E-flat clarinet; and Three Latin Prayers, originally composed for voice. Scelsi is a gifted composer of melodic lines, and his music empowers performers to tell a story or target an emotion. Robinson gives the Three Pieces a dramatic edge, and the latest composition, the Three Latin Prayers (Ave Maria, Pater Noster and Alleluja), is buttery and wistful. The quality of performances and recording sweeps aside other releases (e.g., Ixor played on oboe, Ko-Lho, and Pwyll, with the Ensemble 2e2m on Adda 581 189). Mode promises more Scelsi and more of Robinson, who switches aesthetics for Feldman’s late works with clarinet on Mode 119.

Salvatore SCIARRINO: Le voci sottovetro (1999); Infinito nero (1997-98). Sonia Turchetta (sop.); Carlo Sini (speaker); Ensemble Recherche. Kairos 0012022KAI (http://www.kairos-music.com/). Salvatore SCIARRINO: Luci mie traditrici (1997-98). Annette Stricker (sop.); Otto Katzameier (bass bar.); Kai Wessel (countertenor); Simon Jaunin (bar.). Klangforum Wien, Beat Furrer (cond.). Kairos 0012222KAI (http://www.kairos-music.com/). Le voci sottovetro consists of crumbs left over from Luci mie traditrici, Sciarrino’s opera that’s not about Don Carlo Gesualdo. When Sciarrino embarked upon Luci, it was all about Gesualdo, but when he learned that Schnittke was also working on an opera with the same subject, he dropped all explicit references to the early 17th-century nobleman, composer and murderer. Four discarded orchestrations of Gesualdo’s music became Le voci sottovetro (for the opera, Sciarrino used music of Claude Le Jeune instead). The listener hears readings of letters by Torquato Tasso (1544-1595) between the movements of Le voci sottovetro (both Gesualdo and Monteverdi crafted madrigals from his poetry). Tasso, mentally deranged when he penned these letters in the 1580s, writes about his maladies and anxieties, real and imagined: “I suffer headaches, but not too strong, pain in the entrails, on my side, in the thighs, legs, but only slight pain, vomiting, blood loss, fever have rendered me weak. And in the midst of such horrors and pain the image of the glorious Virgin Mary appeared to me in the air with her son in her arms in a half circle of colors and fumes.” The letters, which Carlo Sini reads enchantingly, break the flow of Sciarrino’s ingenious recasting of Gesualdo’s dances and madrigals. Kairos provides translations. Sciarrino scores Le voci sottovetro for a small ensemble of bass flute, English horn, bass clarinet, violin, viola, cello, percussion and piano. He highlights Gesualdo’s surprising harmonies by frequently changing instruments and timbres. The “Gagliarda del Principe di Venosa” moves abruptly from English horn, violin and glockenspiel to marimba with string harmonics. Infinito nero, the major work on the disc, is a setting of the ravings of Maria Maddalena de’ Pazzi (1566-1607). Maria Maddalena, who came from an aristocratic family, was canonized in 1626. Eight novices followed her about. Four would repeat her ramblings to the other four, who would write them down. Most of the piece is deathly silent with rhythmic key clicks, flute breathing, and rattling string bows. When mezzo Sonia Turchetta erupts in song and speech (she shatters the five minutes of opening quiet), the chamber ensemble (flute, oboe, clarinet, violin, viola, cello, percussion and piano) is helpless against her torrents. The silences in Infinito nero are among the purest ever recorded; what Ensemble Recherche and Kairos have done here is bewitching. After Turchetta, flutist Martin Fahlenbock alternately mimics the voice and makes uncanny breathing sounds. High piano clusters, string tremolos, and pitchless flute noises suggest Lachenmann. Sciarrino claims to have been exploring asceticism and silence. After Le voci sottovetro and Infinito nero, it’s difficult not to approach Luci mie traditrici with apprehension. One anticipates more mystic ravings. The opera’s libretto is derived from Giacinto Andrea Cicognini’s 1664 text about Gesualdo’s discovery of infidelity and subsequent murder of his wife and her lover. Gesualdo was a nobleman. His position in society permitted him to take revenge yet remain above the law. He had others do the dirty work and for the rest of his days thought himself a coward. The opera focuses on the husband’s gradually eroding mental state, culminating with the wife’s murder (the lover is killed offstage). At just over an hour, Luci mie traditrici is a wonderful dramatic bolt. Pared to essentials of expression, the spectacle is fragile, a still pond teeming with piranhas. The chamber orchestra with saxophones is employed delicately, the singers carrying the thrust of the action. The similarity to Le voci sottovetro and Infinito nero is obvious. The “period” music, an elegy by Claude Le Jeune, is dressed up the same way the composer treated Gesualdo in Le voci sottovetro, but set against the opera’s high tremolandi, wailing gestures, and breathy flute noises, it’s enshrined as a museum artifact. Sciarrino’s sinuous settings are striking. He uses a technique I’ve never heard before: The first syllable of a phrase is lengthened, with the final syllables tumbling quickly at the end of a breath. In a duet, the two singers seem to sing past each other alternating held notes and the following salvo of syllables. While the orchestra’s spare background matches Infinito nero, the vocal lines are sensual, almost erotic. Like the disc with Le voci sottovetro and Infinito nero, Kairos’ Luci mie traditrici is an excellent recording with clear silences and fidelity to the score’s rich timbres. The orchestra’s extended techniques pass for electronic music in many places. This is undoubtedly one of the best opera recordings I’ve come across. It’s rare to hear music and silence sound so miraculous. Here at La Folia we’ve raved about the quality of Kairos releases before, and these are among the label’s best.

“Six Duos.”Stefano SCODANIBBIO: Western Lands (1992); Escondidio (1991); Quodlibet (1991); Composte terre (1992); Jardins d’Hamilcar (1990); Humboldt (1994). Irvine Arditti (violin); Dov Scheindlin (viola); Rohan de Saram (cello); Stefano Scodanibbio (contrabass). New Albion NA 113 CD (http://www.newalbion.com/). Contrabassist and composer Stefano Scodanibbio’s ideal string quartet would probably be violin, viola, cello and contrabass. For each of its six possible duo combinations, Scodanibbio has written a fantastic and ingenious duet. Emboldened by the luxury of working with the Arditti String Quartet for several years, he has written virtuosic music that capitalizes upon harmonics, syncopations, and the instruments playing in and out of each other’s ranges. Listening to these pieces is like overhearing an intense technical discussion. Rarely do the instruments rest, so intertwined are their parts. Scodanibbio writes intricate passages that mix harmonics with fingered notes, sul ponticello tremolos that draw out rich frequencies, delicate glissandos, and all sorts of scratching noises. Sometimes the modal pitch material suggests Xenakis, a significant figure in Scodanibbio’s solo repertoire. Several of the duets fade away with complex ostinatos, Western Lands (cello and contrabass) and Humboldt (viola and contrabass). Strangely, the duo for violin and viola, Composte Terre, has been recorded in mono. Most of the duets sound like an eight-stringed instrument played by four hands, which is especially true of Composte Terre’s opening with its vigorous double stops and spidery sul ponticello. It’s hard to determine whether this was a mistake. As always, the members of the Arditti Quartet (Arditti, Scheindlin and de Saram) play magnificently. Scodanibbio is also a marvel to listen to. His music and style bring out the best in the Ardittis, who seem more relaxed, even passionate here compared to some of their Montaigne recordings (Ferneyhough, Lachenmann, Carter, et al.).

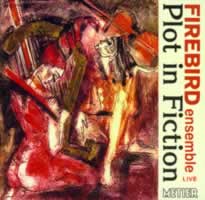

“Plot in Fiction.” Enrico CORREGGIA: Già l’Eolia di Notte (1985). Luca FRANCESCONI: Viaggiatore Insonne (1983); Plot in Fiction (1986). Giacinto SCELSI: Kya (1959). Ada GENTILE: In un Silenzio Ordinato (1985). Dario MAGGI: Im finsteren Wald (1993). Alison Wells (sop.); Roger Heaton (clarinet); Christopher Redgate (oboe). Firebird Ensemble, Barrie Webb (cond.). Metier CD92018 (http://www.metierrecords.co.uk/). Between 1994 and 1997, Metier released live performances of six contemporary Italian pieces by the Firebird Ensemble under the proficient direction of Barrie Webb (who has a second career as a virtuoso trombonist). Opening with blasts of frenetic energy, Enrico Correggia’s Già l’Eolia di Notte takes a bit more than seven minutes finally to wind down to nothingness. Winds, brass and strings take on different material and personalities. After the opening, flutes enter with trills suggesting Nielsen’s landscapes while the violins twitter like mechanical birds. Defying conventional form, the instrument groups gradually intertwine as the work’s pulse slackens and fades away. The form of Ada Gentile’s delicate In un Silenzio Ordinato is similarly unusual, the sparse chamber ensemble evoking night sounds, unsure whether to be soporific or sinister. In the Correggia and the Gentile, the violins occupy the foreground; the works with soloists are more appropriately balanced. Soprano Alison Wells appears in two song settings, Francesconi’s Viaggiatore Insonne and Dario Maggi’s Im finsteren Wald. Maggi’s setting of Georg Trakl’s Passion for voice, clarinet, marimba and piano reveals a distinct sensitivity to Trakl’s potent text. Curiously, Francesconi’s setting of Italian is more Teutonic than Maggi’s handling of German. Viaggiatore Insonne (“Sleepless Traveler” by Sandro Penna) is craggy and restless. Roger Heaton is the clarinet soloist in Scelsi’s concerto-like Kya. With respect to Francesconi’s Viaggiatore Insonne, this is like stepping out into wintry weather from the bustle and warmth of an indoors party. Heaton provides a velvety line to Scelsi’s otherworldly music. The three-movement Kya (slow, slower and fast) builds from a single-pitched background, the clarinet ornamenting the pitch as if tuning. The accompanying ensemble is a mere seven players, but the microtonal playing and the rich layer of harmonies create the illusion of many more. Heaton and Firebird best Rémi Lerner with the Ensemble 2e2m on Adda 581 189, and the clarinet’s timbre is preferable to the saxophone version (Federico Mondelci on Ina Mémoire Vive 262009). Christopher Redgate alternates between oboe and English horn as soloist in Francesconi’s Plot in Fiction, an agitated, irritable composition with a supporting ensemble of 11 players. The difficult solo part calls for repeated notes, double-tonguing and multiphonics. The work is over in a flash. Oboist Marieke Schut’s recording from 1990, with David Porcelijn and the ASKO Ensemble, originally on Attacca Babel 9057-4 and reissued on Montaigne MO 782032, is more diffuse than this Metier recording and lacks the unbridled intensity that makes the piece so exciting. There’s no music by Franco Donatoni in this collection, but he’s definitely in the background. Donatoni is the dedicatee of Francesconi’s Plot in Fiction, Maggi studied with him, and his influence is audible in the Correggia and the Gentile. Yet, it is good to know that a rewarding program of contemporary Italian music can be made without relying upon Donatoni and Berio. We should hear more of the Firebird Ensemble. Their recording on Vienna Modern Masters 3055 featuring music of Margaret Lucy Wilkins (Webb conducts the ensemble and plays Wilkins’ 366″ for solo trombone) is worth seeking out — I’ll cover it after I get back from Italy. [More Grant Chu Covell, Italian Vacation]

[Previous Article:

Further Thoughts on Authenticity]

[Next Article:

Echt und Ersatz: Mahler, Bruckner, Rott, Zemlinsky, et al.]

|