Italian Vacation 5.

|

Grant Chu Covell [November 2007.]

Goffredo PETRASSI: Sestina d’autunno “Veni Creator Igor” (1981-82); Seconda Serenata Trio (1962); Dialogo Angelico (1948). Luigi DALLAPICCOLA: Quaderno Musicale di Annalibera (1952); Tartiniana Seconda (1956); Parole di S. Paolo (1964). Cristina Zavalloni (m-sop), Ensemble Dissonanzen, Claudio Lugo (cond.). mode 166 (http://www.moderecords.com/). Luigi DALLAPICCOLA: Sonatina canonica su capricci di Paganini (1943); Tre episodi dal balletto Marsia (1949); Quaderno Musicale di Annalibera (1952); Inni – musica per tre pianoforti (1935); Due studi (1946-47); Tartiniana Seconda (1956). Duccio Ceccanti (vln); Roberto Prosseda (pno). Naxos 8.557676 (http://www.naxos.com/). Always-reliable mode’s charming portrait of two influential and beloved mid-century Italian composers begins with Petrassi’s spry Stravinsky centenary offering, scored for mandolin, guitar, viola, cello, double-bass and percussion. Contrasting the unusual grouping’s flamboyance, Dallapiccola’s canonic and dodecaphonic masterpiece Quaderno Musicale di Annalibera for piano solo takes second position. United with a 1904 birth-year, Petrassi and Dallapiccola maintained different locales, the former residing in Rome, and the latter outside Italy. Webern’s succinctness branded both, especially evident in Petrassi’s luscious Seconda Serenata, as if the harp, guitar and mandolin had stolen away from Webern’s Op. 10 for a wild threesome. An unbarred prelude soon plunges into swirling handfuls of resonant sevenths and ninths, like glass shards which can tinkle or gash. Dallapiccola’s canonic mastery drives the violin and piano Tartiniana Seconda, the composer’s further exploration of Tartini material. The four-minute flute duet Dialogo Angelico announces Petrassi’s modernist mien, suggesting he found his true voice among stringed instruments’ ephemeral plucks. Dallapiccola demonstrates his way with unusual formations in the dramatic Parole di S. Paolo (first letter to the Corinthians, chap. 13) for voice and instruments. Finely played; Ensemble Dissonanzen and mode easily nail Petrassi’s Sestina and Serenata’s tricky ensemble balances. Naxos collects Dallapiccola’s four piano works plus the two violin / piano duos. An energetic player, Prosseda’s Romantic nature suits the early three-piano Inni and the expressionist reductions from the ballet Marsia; however, the untailored Quaderno Musicale di Annalibera fails to persuade. Violinist Ceccanti brings a 1667 Amati to Prosseda’s Kawai (!) for the translucent Due studi. Both old-style pieces, the delightful solo-piano Sonatina canonica builds from Paganini themes. The duo Tartiniana Seconda tempers tonality with momentary dissonance. The balance Ceccanti and Prosseda achieve reveals a seasoned cross-familiarity. More Petrassi? Double-disc set Stradivarius STR 33700 houses all eight Concertos for Orchestra with the Netherlands Radio Symphony Orchestra under Arturo Tamayo. Contemporaneous with the bewitching Seconda Serenata Trio, the red-meat Settimo Concerto (1961-64) receives a blistering performance.

Bruno MADERNA: Satyricon (1971-73). Paul Sperry (ten); Aurio Tomicich (bass); Liliana Oliveri (sop); Milagro Vargas (m-sop); Divertimento Ensemble, Sandro Gorli (cond.). Naïve Montaigne MO 782174 (http://www.naiveclassique.com/). Distributed in the US by Naxos (http://www.naxos.com/). Bruno MADERNA: Concerto for Oboe and Chamber Ensemble No. 1 (1962); Concerto for Oboe and Orchestra No. 2 (1967); Concerto for Oboe and Orchestra No. 3 (1973). Fabian Menzel (ob), Rundfunk-Sinfonieorchester Saarbrücken, Michael Stern (cond.). col legno WWE 1CD 20037 (http://www.col-legno.com/). Distributed in the US by Qualiton (http://www.qualiton.com/). Premiered in its composer’s final year, Maderna’s Satyricon is a ribald, polystylistic circus. Four vocalists weave through English, French, German and Latin as the accompanying chamber orchestra lurches between plainchant, hardened serialism, salon waltzes, Carmen, Aida, Tchaikovsky’s First Piano Concerto, Mozart’s Requiem, etc., etc. The overture introduces the first of several concrète episodes. Echoing B.A. Zimmermann (d. 1970) and presaging Ligeti’s Grande Macabre (1975-77), perhaps Satyricon was Maderna’s gentle riposte to the Darmstadt aesthetic — evidently there were no hard feelings, as Boulez created Rituel in memoriam Bruno Maderna immediately following. This fluent recording admirably captures Satyricon’s volubility. Intellectual but never academic, the composer / conductor’s oboe concertos bear a serious demeanor. But three of them? Maderna thought the oboe ideal for delivering the perfect aulodia (melody). In the First, the soloist bounces between oboe, oboe d’amore and English horn. Orchestral flourishes rich in exotic percussion interrupt spiky cadenzas. The Second’s opening wind chords suggest an accordion, late Stravinsky or, paraphrasing another reviewer’s observation, an overture to the careers of a few Dutch composers. Menzel’s liquid sound shimmers loftily in the central concerto, evaporating into beguiling mobiles. The shortest of the three, the Third, displaying brash tuttis and piercing shrieks quite unlike the earlier concertos’ sparse chamber textures, arrays soloist and orchestra like estranged colleagues.

“Musica per mandolino e liuto.” Antonio VIVALDI: Concerto for two mandolins in G major, RV 532; Trio in G minor for violin, lute and continuo, RV 85; Concerto in C major for mandolin, RV 425; Concerto in D minor for viola d’amore and lute, RV 540; Trio in C major for violin, lute and continuo, RV 82; Concerto in D major for lute, RV 93. Rolf Lislevand (mandolin, lute, guit.), et al. Naïve OP 30429 (http://www.naiveclassique.com/). Distributed in the US by Naxos (http://www.naxos.com/). “Doubles Concertos.” Antonio VIVALDI: Concerto grosso, RV 156; Double Concerto, RV 535; Concerto for Violin, Op. 3, No. 12, RV 265; Double Concerto, RV 531; Double Concerto, RV 522; Concerto grosso, RV 574. Akademie für Alte Musik Berlin. Harmonia Mundi HMC 901975 (http://www.harmoniamundi.com/). For the 26th release of its ambitious Vivaldi undertaking, Naïve offers works featuring mandolin or lute. (The four lute works, RV 82, 85, 93 and 540, were previously released on Naïve 8587; the mandolin concertos were recorded in 6/2006.) Quite unlike yesteryear’s overstuffed performances, these sparkly, intimate performances generally allot a single instrument to each ensemble part. Generations have been imprinted with the slow movement of the D major concerto, RV 93, as the backdrop for one of Sesame Street’s early music videos, and the C major concerto, RV 425, was (ab)used on Kramer vs. Kramer’s soundtrack. RV 425 unwinds delicately, pizzicato strings matching the gentle mandolin. The troupe sensitively shapes phrases with crescendos and decrescendos especially in the dreamy slow movements. No conductor is specified, so presumably nimble-fingered Lislevand leads. (Players include Manfredo Kraemer and Guido Morini.) These lute and mandolin concertos brighten the soul. Bracing sunlight pervades the Akademie für Alte Musik Berlin’s release of six Vivaldi concertos. Except for the brisk Op. 3, No. 12, these compact works contrast instrument pairs (oboes, cellos or violins) or groupings (strings, a miscellany of violin, bassoon and two each oboes and horns). Subtly flexing tempos and alert continuo transcend the red-haired priest’s familiar knitting machine. RV 574, presumably written for a Dresden band, reveals a Germanic Vivaldi, quite unlike the rest. This one would easily blend with the Akademie’s spry 2002 Telemann release (HMC 901744) featuring similarly unanticipated cross-border influences.

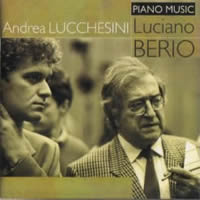

“Piano Music.” Luciano BERIO: Sonata per pianoforte solo (2001); Six Encores (1965-90); Rounds (1967); Sequenza IV (1966); Cinque Variazioni (1952/53, rev. 1966); Touch (1992); Canzonetta (1991). Andrea Lucchesini, Valentina Pagni Lucchesini (pno). Avie AV2104 (http://www.avierecords.com/). Distributed in the US by Forte Distribution (http://www.fortedistribution.com/). Ever a romancer of the past, Berio revered Classical forms. Only one Sinfonia and Quartetto left his workshop, and in 2001, he completed his sole sonata, a large, 23-minute single movement for piano alone. The work’s dedicatee, musicologist Reinhold Brinkmann’s booklet remarks divulge three featured ingredients: Wagner’s Tristan chord, the E major / E-flat major chord from Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring and the opening repeated chord from Stockhausen’s Klavierstücke IX. However, these historically weighty verticalities are anything but obvious. Berio’s Sonata is not a scholar’s buffet. From the outset we meet a repeated note, as in Le Gibet from Ravel’s Gaspard de la Nuit, which operates as a tightrope upon which filigree and outbursts dance and mingle. Lucchesini admirably delineates simultaneous moods and layers. I hear connections with the Sinfonia’s final movement and Eindrücke (1973-74), orchestral works balancing stasis and frenzy. Most tellingly, the Sonata offers embellishments and crystalline improvements upon Sequenza IV’s comparatively angular lines. Even within Lucchesini’s felicitous interpretation, Sequenza IV comes across as an antique junk drawer. The six encores, Brin (1990), Leaf (1990), Wasserklavier (1965), Erdenklavier (1969), Luftklavier (1985), and Feuerklavier (1989) waft by like airborne seeds, each with its texture or mode. The nostalgic Wasserklavier breathes Brahmsian vapors. Rambunctious Rounds strictly notates a graphically indicated harpsichord bagatelle. The Lucchesini husband-and-wife duo premiere Touch and Canzonetta, two unpublished four-hand miniatures written as gifts for the pianists’ family. Regrettably, these are not Berio’s complete piano works. David Arden’s 1996 New Albion disc (NA 089) staked that claim, obviously lacking the Sonata, but including the succinct, neo-classical Petite Suite (1947) which Lucchesini’s program could easily have absorbed. Cinque Variazioni remains the only apprentice work, a Dallapiccola-influenced collection.

[More Grant Chu Covell, Italian Vacation]

[Previous Article:

Armchair Operas 1.]

|