Label Report: Hat Hut Records

|

Mike Silverton [August 1999. Originally appeared in La Folia 2:1.] This marks my third hatART label report. Why the untoward attention? Simple. From its inception in the LP era, Werner X. Uehlinger’s Hat Hut Records of Therwil, Switzerland has been issuing some of the most interesting and engaging music on disc. The label’s tenacious capo has very firm ideas about where music ought to be going. As to a compass heading, Hat’s dual list of jazz and (mostly) new classical proceeds at a salubrious remove from bloated postmodernist pastiche and kitsch. For this writer, it’s been a tutorial. Abandoning terms like avant garde, modern or modernist to history, one nonetheless asks when in living memory so much dreck passes for nourishment? When has a movement — classification? era? slot? — the equivalent of postmodern served as an excuse for so depressing an abundance of retrograde pabulum? One’s questions are of course rhetorical. There have been over the years a number of hatART releases I’ve not responded to, but never have I perceived evidence of intellectual dishonesty or pandering to laziness. And this of course addresses in general an independent label’s strength, and in particular Uehlinger’s self-assigned mandate. The wonder of it is the quantity and quality of hatART releases. One-man stewardship notwithstanding, it’s absurd to refer to Hat Hut Records as a “little label.” The coverage to follow is in no particular order. For brevity’s sake, those few hats that fail to engage my enthusiasm I’ll mention but sketchily.

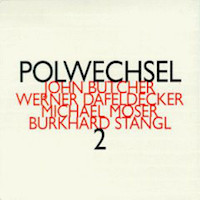

Polwechsel, hat[now]ART 112, released in 1998, consists of a quartet: Radu Malfatti, trombone; Burkhard Stangl, guitar; Michael Moser, cello; Werner Dafeldecker, double bass, guitar. For Polwechsel 2, hat[now]ART 119, released in 1999, John Butcher, tenor and soprano saxophones, replaces Malfatti; in addition to double bass and guitars, Dafeldecker manipulates electronics. There is a branch of new music called Noise. I don’t propose to pursue a connection which is really more a term of convenience. I mention it only as a superficial and possibly even harmful suggestion at categorization. I wish there were an term to describe an impasse of the fingertips corresponding to tongue-tied. Be that as it may, I think I can make a few illustrative statements without fear of harming the delicate balance in these two releases between indeterminacy, strategy, and hair-fine precision. First, one does not attempt to operate at this extreme distance from convention with other than masterful, like-minded players; second, Polwechsel 2 is the more austere and challenging program. In both Polwechsel and Polwechsel 2, Werner Dafeldecker plays the larger part, not as performer but rather as composer of Nord, Ost and Sudwest (Polwechsel), Hyogo and Toaster (Polwechsel 2). Given the ensemble’s supremely abstract character, one notes with interest that Michael Moser’s NNO-Fernaumoos (Polwechsel) and Tatoo [sic] (Polwechsel 2) seem the more musically coherent compositions, with the latter’s nervous enegies in keeping with tattoo’s definition: raising an alarm by means of a rapid drumbeat, etc. I do not intend for a suggestion of coherence to imply superiority. However “incomprehensible” the particular moment or event, the thing that most impresses about Polwechsel as an ensemble is the sense it conveys of knowing exactly what it’s doing and where it’s headed. If Dafeldecker’s five compositions play relative to Moser’s two closer to noise (there, I said it!), rest assured, it’s no accident. Falb of Polwechsel 2 is a group project. To return to what I’ve been saying about Uehlinger’s judgment and mission, this is the kind of thing any assemblage of overweening weenies feel they can pull off. All one needs do is grunt, scratch and squeak. I think not. To understand what Polwechsel accomplishes (in either combination of players), one has to hear these discs. Not, however, for hum-along types. As I’ve already done a label report of Georg Graewe’s Random Acoustics, it’s appropriate to note John Butcher’s participation, again on tenor and soprano saxophones, in an RA disc I did not mention then, Concert Moves [RA 011], with John Russell, acoustic guitar and Phil Durrant, violin. The sessions, dating from ’91 and ’92, reveal what differences of temperament attach to seemingly inchoate and therefore presumably indistinguishable ensemble exercises. Until electronic devices programmed for random activity engage in improvisation — and here too I have my doubts — personality informs the event, as a truism that applies even to John Cage’s aleatory work. Our colleague Scardanelli reports in his Motley on a quite remarkable disc in which John Butcher participates, Navigations / Chris Burn’s Ensemble / Acta CD 12. Udo Kasmets / Pythagoras Tree / Works for Piano / Stephen Clarke, piano. To return again to Uehlinger’s perspicacity, here is music by a Lithuanian-born (1919), naturalized Canadian known, I should think, to precious few. To make matters even more interesting (and they are, I assure you, interesting), the seven-part program is identified as first recording. In truth, I ought to have said six part, one of which, Timepiece, is performed twice, albeit to rather different effect. From Art Lange’s excellent notes: “Timepiece [of 1964 is] the only totally graphic score. … [S]et into a square box intersected by straight lines, [it] may be turned and read in any direction and performed by any instrument. This is Kasmets at his most Cagean … ,” and also gives us a fair idea of where we stand. The piece entitled 3/7 D’un Morceau en Forme de Poire toys with its Satie predecessor which, as Lange points out, is entitled Trois Morceau, etc., but consists in fact of seven morsels. The titles Feigenbaum Cascades and Music of the First Eleven Primes (1994, 1995) reveal Kasmets’ interest in mathematics, and one does indeed experience the music’s general demeanor as an expression of cool, abstract elegance. Seek elsewhere for histrionics. Again fair warning: not for hum-alongs. The recording, by John Sorenson with Reid Kruger’s assistance at the Banff Center in Alberta, is remarkably good — superbly dynamic, with just the right sense of acoustic space. Produced by Michael Hynes. A short biographical note about the fine pianist, Stephen Clarke, would have been helpful. Giacinto SCELSI / Kya / Marcus Weiss, soprano, alto, bass saxophones. Philippe Racine, piccolo. Johannes Schmidt, bass voice. Ensemble Contrechamps (Isabelle Magnenat, viola; Daniel Haefliger, cello; René Meyer, clarinet; Sylvain Lombard, english horn; Pascal Geay, trumpet; Ives Guigou, trombone; Denise Schoechlin, horn). Pierre Stéphane Meugé, baritone saxophone; Alberto Geurra, contrabassoon; Jonathan Haskell, double bass; Francois Volpé; percussion. Jürg Wyttenbach, conducting both ensembles. To clarify the headnote, the second group of instrumentalists accompanies bass Johannes Schmidt in Yamaon (1954-58). One wee complaint: the equivalent to the traycard of Hat Hut’s paper wraps requires a background in cryptography in connecting works to performers. However, Jürg Wyttenbach’s name stands out like a flare. Until I hear evidence to the contrary, which I doubt will soon happen, I’ll remain convinced that Wyttenbach is the world’s premier Scelsi conductor. His direction of the Italian count’s large-scale works on the Accord label established for me some years ago Scelsi’s unique significance. (He died in 1988.) This conduit to the cosmos (which is how he saw himself, publicly at least), sidestepped what he viewed as serialism’s strictures in the cultivation of a microtonal technique peculiarly his. It’s important to frame this solo flight within Scelsi’s Eastern-flavored mysticism, about which your cynical reporter detects a whiff of balogna. Not that it matters to the outcome, yet one cannot take entirely seriously Scelsi’s mock-modest self-demotion to that amanuensis to the Great Whatevers. No composer, he; an other-directed seismograph rather. From annotator Art Lange’s remarks: “Like John Cage, Scelsi disagreed with the rôle of the composer as arbiter of taste or controlling agent, but he took a different philosophical and thus compositional tack … [W]hen he returned to composition following … a personal and spirutual crisis [elsewhere described as an extended nervous breakdown], he escaped the total control (Stockhausen, Boulez) vs. indeterminacy (Cage) controversy of the time by adopting the belief in composer as “medium” — a vessel through which cosmological concepts of sound production could flow.” Two observations: the cosmos sounds remarkably Scelsian; similarly (no tautology intended), John Cage’s aleatory exercises sound like the music of John Cage. As I see little of value in the achievement of anonymity, an irony of failure serves as no impediment to the enjoyment of either composer’s efforts. Kya is hatART’s fourth Scelsi disc. I judge only one, CD 6148, released in ’94, less than a total success. A mixed program, Scelsi, Byzantium, The Alchemists fails to make its connections, with particular regard to five not especially interesting fugues by the 17th century alchemist Michael Maier. Okanagon [hatNOWseries 6124] and Bot-Ba [hatNOWseries 6092] demand inclusion on the modernist maven’s shelf alongside the disc here reviewed, an exemplar as usual of performance and production (in the event, co-production with West German Radio, Köln, and Marcus Weiss, the featured saxophonist). The release takes its title from a three-movement work of 1959 for viola, cello, clarinet, english horn, tumpet, trombone and horn. Merely in the reading, one senses the music’s dark amber coloration. Deeper shaded still, a baritone saxophone, contrabassoon, double bass and percussion fortify Yamaon’s bass voice. Like Scelsi’s Songs of Capricorn, this three-part work of 1954-58 puts the vocal line to an urgent, shamanistic exhortation. Again in three parts, Rucke di Guck of 1957 is an absolute charmer for piccolo and soprano saxophone (I’m guessing at the sax — the notes also neglect to comment on an intriguing title). Maknongan of 1976 is here performed on bass saxophone and in the abovementioned Okanagon by Joëlle Léandre’s double bass. No one’s taking liberties. Scelsi specified only the work’s spectral range. Weiss performs Ixor (1956) and Tre Pezzi (1956) on alto saxophone, or so it sounds. Those notes! Which include, happy to say, a personal recollection by Wyttenbach. A terrific release, not to be missed. An epiphany with regard to the music of Morton Feldman began about ten years ago with a slow, steady succession of hatART releases, the latest and surely among the finest of the lot, For John Cage, with violinist Josje Ter Haar and pianist John Snijders, both of the exemplary Ives Ensemble of the Netherlands, hat[now]ART 124. Till it arrived, I doubted I’d ever hear a better-performed, better-recorded performance than that on a Japanese label imported by Joseph Celli’s OO Discs: ALM Records ALCD-41, two CDs, Yasushi Toyoshima, violin; Aki Takahashi, piano. ALM’s remarkably handsome packaging contains a fold-out mesostic (a slender column of words down the center of which in upper case appear a string of MORTON FELDMANs). The Japanese performance runs 97:40, the hatART performance, 69:12, thus a single CD. Feldman allowed performers freedom of pace; all else is carefully notated. Therefore the disparity in time taken to get to the end. As with a number of hatARTs, For John Cage is a co-production, in this case with Hessian Radio, Frankfurt. A friend, an old recording engineer, stopped by for a visit and we got to talking about gear. He observed from experience that Europe’s state-supported electronic media generally spring for the best. In the hearing, it does seem the case. A poor-quality recording produced by any of Germany’s electro-cultural apparats is the rare exception, which also addresses, of course, technical savoir-faire. Huzzahs therefore to Recording Supervisor Richard Hauck and Sound Engineer Thomas Escher. If you don’t know much about his music, this splendid example of Feldman’s unruffled, ever-shifting, minutely detailed way with the skimpiest of materials seems to me as good a place as any to launch your investigation. Feldman, who died in ’87, remains for me the New York School’s stellar figure. For John Cage is Hat’s 14th release, several of these multiple sets, in its Feldman survey. A similar, thus far modest voyage of discovery is likewise under way for Roman Haubenstock-Ramati: the first, issued in ’96 is Pour Piano, with pianist Carol Morgan, hat NOW Series CD 2-6196, two discs; in ’97, Graphic Music, with Eberhard Blum, flute, voice; Iven Hausmann, trombone; Jan Williams, percussion, hat[now]ART 101; and finally (for now), two recent arrivals, Concerto a Tre, with Ensemble Recherche, hat[now]ART 114; and Mobile for Shakespeare, with Ensemble Avantgarde, Beat Furrer, conducting, and Leipzig String Quartet, hat[now]ART 118. Don’t be embarrassed. I didn’t know much about him either. Never has the saying better late than never served a more useful end: for one thing, the man does appear to be a significant voice in modernist music; for another, his work is remarkably attractive (even, possibly, to those who think they dislike this kind of thing). Graphic Music, issued in ’97, is a terrific disc in an edition — take note! — of 1500. Best to make enquiries now. (Hat editions have been for some time now in a uniform 3000 pressings. If Graphic Music sells out, I’d not be surprised to see it as a reissue, a recommendable example of which is Fritz Hauser’s Solodrumming, hat[now]ART 129.) As Graphic Music’s title suggests, the three performers (Everhard Blum, flute, voice; Iven Hausmann, trombone; Jan Williams, percussion) respond not to conventional notation but rather to what look like works of abstract art. Consequently, what one hears reflects in large part the considerable creative abilities of these three especially. Blum’s vocalizations are in a class by themselves. As a matter of principal — not of default — several composers of the avant garde, Haubenstock-Ramati prominent among them, intend for performers to participate in the creative act. As a matter of bug-in-amber inevitability, once such open-form activities are locked into a recording, what was free is no longer so. Speaking for myself, this is no cause for concern because I love what I hear (however often). For the purpose of illustration, let’s consider a lovely thing from the disc entitled Concerto a Tre. Für Kandinsky (1987, revised 1989), a trio for flute (Martin Fahlenbach), oboe (Jacqualine Burk) and clarinet (Uwe Möckel), plays for this listener as a perfect little gem, pastoral in character, calm in temperament, as exemplified by its leisurely pace and subtle dynamic gradations. Has you asked, I’d have declared it strictly notated, conventional even — nothing could be more obvious. Yet allow me to quote from Reinhard Kager’s good notes. I won’t trouble you with the Kandinsky connection. But this part is significant, at least to my impression: ” … the seven sheets of music … have only a single part to be read horizontally, divided into three sections, within which … the successive entries of the players are marked with 1, 2, and 3. Which instrument takes on what part is [unspecified], but the order in which the instruments play the individual sections is: instrument 1 plays A > B > C, instrment 2 plays B > C > A, and instrument 3 plays C > A > B. The same part is [thus interpreted] three times and merged into one another in a different order [!]. If it meant my life, I could not have guessed the plan of attack. Compliments therefore to the players for making Für Kandinsky sound so — what’s the word I want? Ah yes, sedate. Simple sybarite that I am, I’m merely hearing wonderful music including, of course, the disc’s title work, Concerto a tre, for piano, trombone and drums, which I compare elsewhere to some quite abstract jazz I’ve been hearing of late. Recommended with all possible enthusiasm to the collector with an interest in European post-war art music, as well (with due caution) to the generalist. Superb recordings, all. As is hat[now]ART 118, Roman Haubenstock-Ramati / Mobile for Shakespeare, performed (to repeat) by the Ensemble Avantgarde, Beat Furrer, conducting, and the Leipzig String Quartet. Credentials or Think, Think, Lucky (words by Beckett) and Mobile for Shakespeare date from 1960, a chronology which, given the music’s extraordinary modernist features, positions these pieces as milestones. Both works, for percussion-rich instrumental ensemble and soprano voice (Salome Kammer and Kerstin Klein respectively), play as marvels of filigree texture, as a quality that springs to mind with regard to this composer overall. Given their texts, Mobile for Shakespeare is, quite properly, the more delicate of the pair for voice and instruments. But I no less respond to Credentials’ (relative) rumbustiousness. The merits of the semi-gentle, mallet-&-metal Liasons of 1958 and the intermittently, not to say surprisingly Sturm und Drangish Second String Quartet of 1977 I leave to the reader to discover. Impeccable performances and another quite perfect Sender Freies, Berlin, co-production with Hat Hut Records, Wolfgang Hoff, recording supervisor. Aldo CLEMENTI / Madrigale / hat[now]ART 123. A delight to salute hatART’s attention to our period’s Italian branch. The performers of these ten chamber pieces (including the eponymous Madrigale) are the Ives Ensemble of the Netherlands, a superb new music band who’ve appeared on other hatART releases. Clementi, born in 1925, is an especially rare bird, I should think, among American collectors. I’ve only a Ricordi CD, courtesy of Qualiton Imports, entitled Opere Scelte [CRMCD 1004]. Composers who think about where they stand in the history of their art and thus about their roles — not all certainly, but a significant few — tend to write music the implicit subject of which reflects these concerns. From one listener’s perspective in the midst of all this activity, a reluctance on the part of living composers in the avant-garde tradition to engage the past’s upholstered rhetoric seems another shared characteristic, among the Italians especially. We’ve only to consider the fine-textured, shard-like qualities of Luigi Nono’s music, for example, or the brittle-bright, music-box character of Franco Donatoni’s work. From what one hears (with delight) of this hatART disc, Clementi falls temperamentally within this miniaturist, exquisitely articulated milieu. The disc’s good annotator, David Osmond-Smith, comments on Clementi’s frequent employment of canon form as a means to an end. In brief, the music is cool, unhurried, timbrally complex yet transparent, with an intelligence of structure and utterance that ought to delight the discriminating ear. Good Dutch recording and, from what I can tell, impeccable performances. ENFANTS TERRIBLE / Steffen Schleiermacher, piano / hat[now]ART 121. A howler of a misnomer, this. In order to qualify as a musical enfant terrible here at century’s end, you’d need to spin off preludes and fugues to the cries of boiling puppies or farts. Nothing here is in the least terrible, at least in the sense épater le bourgeois. John Zorn’s Carny of 1989/96 is merely weak tea. In quite the opposite direction, Nicolaus Richter de Vroe’s Gabbro (Steinstücke #1), 1988, irritates by virtue of thumping repetitions. Tom Johnson’s three-minute Tango and Sven Ake Johansson’s 19-minute Vom Gleichwertigen und Ungleichwertigem are not without their attractions, yet, having heard Schleiermacher’s own klavier&klaviere, one wishes Enfants Terrible had been a showcase for his music alone. It’s an intriguing piece consisting, as the title suggests, of overlays of piano sounds (electronically achieved and thus a recording event). A fast-paced, spiky motif explodes, after close to six minutes of developments and turns, into an expanded soundfield, as a most knowing and sophisticated employment of a recording studio’s possibilities. The pace is then retarded, dismantled — all manner of exhilirating turns. Refreshing, energizing, illuminating, even rhapsodic by fits and starts, but épatistically terrible? Anyway, worth the price of the disc. (The title I’ve belabored obviously continues in a deceptive posture struck by a 1994 Schliermacher release, The Bad Boys! [Henry Cowell, George Antheil and Leo Ornstein, hatART CD 6144]). And now to a number of hatOLOGY releases. (As the reader is perhaps aware, hatOLOGY as a category replaces the older designation hat Jazz Series.) CLUSONE 3 / Rara Avis / Michael Moore (alto saxophone, clarinet, melodica); Ernst Reijseger (cello); Han Bennink (drums) / hatOLOGY 523 (55:50) I understand that this trio has disbanded. If true, we’re fortunate to have these 1997 Rara Avis sessions. The title alludes in a characteristically whimsical way to program, which has to do with avians by way of titles: Tico-Tico, St Saëns’ The Swan (of all things!), My Bird of Paradise, a nifty little turn on Yellow Bird, and so on. The ever excellent Peter Pfister recorded, so marvelously well, in fact, that I have used this disc several times already in its early career on my shelves as a demo for audiophile visitors (whose musical horizons lie, as a rule, about a half-yard distant). The mood is archly humorous and quirky, consistent with the Clusone 3’s general world-view. As virtuosic a small mob as ever I’ve heard, the trio displays great wit and bravura skills. The sequence of events is interesting too: Michael Moore’s rather abstractly introspective Secretary Bird appears in the program between that lovely Andean folksong El Condor Pasa in a disarming interpretation which, while honoring the music by never departing it’s simple spirit, spins it into something rather special. On Secretary Bird’s far side appears a raffishly straight-ahead reading of When the Red, Red Robin Comes Bob-Bob-Bobbin’ Along. It’s that kind of program, crazy like a fox. In several of these numbers, Reijseger sounds very much the mellow guitarist. Moore remains for me one of the most seductive reed players on the scene, and Bennink, of course, is his crafty, madcap self. Rara Avis is my favorite Clusone 3 CD. The others in my collection (at no great distance from my affections): I Am an Indian, Ramboy 05, also available as Gramavision GCD 79505. See also Love Henry, Gramavision GCD 79517, and a disc entitled simply Clusone 3, Ramboy 01. Ramboy is one of the good and interesting labels BVHaast of the Netherlands distributes, email wbk@xs4all.nl, attention Susanna von Canon. In the US, try Cadence / NorthCountry. I’ll be doing a BVHaast report soon. Forgive an audiophile’s bass-ackward ingress: Dissonant Characters / Ellery Eskelin (tenor saxophone); Han Bennink (drums) / hatOLOGY 534 (58:42) is another Peter Pfister masterwork. Yet what I esteem another does not. An American recording engineer whose work I also admire — like Pfister, a specialist in small-scale recording, jazz ensembles mostly — is no fan, and I think I understand why. What I perceive in Pfister’s work as resolution’s nth degree, as a celebration of transparency and dynamic detail, plays for my guest as artifice. He once remarked, “This is not how these people sound,” referring to another Pfister recording I played for him here in my digs. His own recordings tend toward truth-in-venue. One can almost smell the milieu in which his ensembles recorded, and this is of course a lovely thing. With Pfister, one hears a kind of crystal-pure idealization. Your reporter became a victim of the condition medical professionals call audiophilia nervosa via discophilia, a no less clinical state, its chief symptom a preference for canned sound. Pfister, as I hear him, is after upper-case Perfection, which almost by definition stands apart from seamy-side life. These thoughts, emptied of their hot air, might have read: One rarely hears such microscopically etched detail in any live setting, particularly with regard to jazz, which is generally amplified and therefore coarsened. Finally, so distinctive is their signature, I can usually identify either’s work. A brilliant notion, recording saxophonist Ellery Eskelin and drummer Han Bennink together. Were it not for the elegance of their spiky interplay, one would have liked to call it a dogfight made in heaven. Eskelin says in the notes to One Great Day [hatOLOGY 502], “In some ways I think that a recording is the best medium for this music. I can think of a lot of music that speaks better on a recording than it does in a club where the environment and the audience’s expectations exert an effect on the music … .” The applause one hears in Dissonant Characters somewhat blunts his point’s universality, but I offer it anyway in lame defence of discophilia. (One Great Day, with Andrea Parkins, accordion and sampler, and Jim Black, percussion; see also Kulak 29 & 30, same trio [hatOLOGY 521].) We lose useful words to co-option. Gay for example. There’s a Hungarian restaurant in London’s Soho, The Gay Hussar. Try contemplating the image of a gay hussar in those innocent, martial terms the establishment’s founder intended. I dare you. In jazz, Fusion is another such. Synthesis is all right, I suppose, but how to overlook synthetic, its ambivalent adjective? Better to revive fusion without baggage, since no other term so handily conveys the seamless, effortless conflation of jazz and art-music idioms the composer-clarinetist-saxophonist Guillermo Gregorio achieves. In Red Cube(d) [hatOLOGY 531, Gregorio, clarinet, tenor sax; Pandelis Karayorgis, piano; Mat Taneri, electric violin], Gregorio’s fourth hatART release, a synthesis occurs one would not have possible were it not for an equally revelatory predecessor, Ellipsis [hatOLOGY 511, Gregorio, alto sax, clarinet; Gene Coleman, bass clarinet; Jim O’Rourke, acoustic guitar, accordion; Carrie Biolo, vibes; Michael Cameron, bass]. Gregorio’s first hatART CD, Approximately I liked on its own terms without, however, sensing events to come [hat Jazz Series CD 6184, Gregorio, alto sax, clarinet; Eric Pakula, tenor and alto sax; Mat Maneri, violin; Pandelis Karayorgis, piano; John Lockwood, bass]. Ellipsis is one of a very few CDs in which the fusion we speak of works absolutely, an unqualified success. Jazz writer John Corbett speaks of Gregorio’s “highly personal new take on the post-Tristano / post-Webern chamber improvisation lineage.” Post-Webern strikes an unfortunate, reductionist note: Schumann as post-Beethoven, say. Chronologically post, to be sure. Yet one listens to Webern as one swallows cod-liver oil, less for kicks than self-improvement. One listens to Gregorio and his players — Mats Gustafsson, tenor sax and fluteophone; Kjell Nordeson, percussion in Background Music [hatOLOGY 526], the disc from which I quote Corbett — for the fun of the thing. Brainy fun, to be sure, but fun nonetheless. Which returns me to Red Cube(d) and Ellipsis, a refresher in the latter restoring its place as a desert-island selection, against which Red Cube(d) would most certainly compete. Whether casually or by design, Corbett’s chamber-music designation elevates these discs to a pinnacle where pipsqueaks tend to perish. Excepting Approximately (and I may well be wrong about that), I see Gregorio’s hatART releases as long-term classics. I hope there are more down the line. Maneri, père et fils, continue a successful hatART run with the Mat Maneri Trio / So What? [hatOLOGY 529] and father Joe Maneri’s Quartet in Tenderly [hatOLOGY 525]. For the trio, we’ve Mat Maneri, electric violin; Matthew Shipp, piano; Randy Peterson, drums. For Joe’s Maneri’s Quartet, himself on tenor and alto saxes, plus clarinet; Mat, 6-string electric violin; Ed Schuller, bass; Randy Peterson, drums. (Note Peterson’s presence in both programs. Anything Matthew Shipp participates in is bound to exhibit a peculiarly turbulent humidity, and So What? is no exception. But it’s the other Mat’s show, and that’s apparent too. It’s also clear that that the son has taken to heart his father’s investigations into expanded tonalities. One hears similarities along with striking dissimilarities. In these present releases, for example, Mat’s trio plays, remarkably as a single-minded entity, the anxious abstractionist to Joe’s expressionist distortions of recognizable fare. There’s a guerilla-warfare quality to So What? — a milieu in which violinist, pianist and drummer dart in and out of their utterances. The issue of tonality simply fails to make an appearance. It’s more a question of gestures and blurs. By contrast, for the first few minutes of Tenderly, one wonders whether the quartet would have passed the highway patrol’s sobriety test. One soon realizes that wobbly footwork through rather more coherent forms is what the music’s about. One’s surprise, in truth, is a rhetorical convenience. I knew more or less what to expect. Here, the emphasis is on less: genius brings about its own astonishments. I hear a whimsical and at the same time subversive humor in Tenderly that I’d recommend, however, only to someone willing to go along for the ride. The casual jazz enthusiast will not be disappointed but rather, perhaps, infuriated. There’s a much more aggressive thrust in the work of either Maneri than that of Gregorio, whose equally daring adventures are the more soft spoken and serene. A jazz quartet, one of whom is a cellist, bodes well. We know before we listen that tradition is denied in pursuit of some other aim. Jon Lloyd / Four and Five aims elsewhere and succeeds [hatOLOGY 537, Lloyd, alto and soprano saxes; Stand Adler, cello; Marcio Mattos, bass; Paul Clarvis, drums and percussion]. One might also correctly assume that a cello along with a bass makes for warmish textures. True enough, but the surprise here is the interplay. Mattos does a good deal of bowing. Paul Clarvis’s dual rôle as drummer and percussionist looks to modernist music especially, where percussion achieves heights of exquisite delicacy. One hears precious few straight-ahead romps. The long (11:32) title work, Four and Five, is a sinuous little masterpiece of a near-orientalist cast. Of the hatOLOGY releases I’ve so far discussed, Lloyd’s is the least improvisational-sounding. Perhaps it’s the stately pace. In any event, I detect more deliberateness than I do deliberation. The other long work (10:52), Blues for, shares with Four and Five nimble-fingered passages of, again, a moody, Eastern flavor. I find a lot of titles pretentious. Rather than some faux-whimsical-mystical handle, a simple number designation would have done (excepting maybe Anthony Braxton’s eye-crossing formulations). But the title work of an invaluable re-issue, Clichés, rings a bell, tho more than likely ironically. Steve Lacy, whose hatART list is already quite long, appears in this 1982 excellent Peter Pfister digital recording at IRCAM in Paris with an ensemble called the Steve Lacy Seven (Lacy, soprano sax; Steve Potts, alto, soprano sax; George Lewis, trombone; Bobby Few, piano; Irène Aebi, cello, violin, voice; Jean-Jacques Avenel, bass; Oliver Johnson, percussion; and in Clichés, Sherry Margolin, Cyrille few “and his friend,” percussion: hatOLOGY 536). Lacy in his customary mode fairly wallows in free jazz liberties, again customarily, toward the raucous side of things. So perhaps the (non)cliché has a little to do with how this long (22:23) piece evolves as a masterly transition from remarkably delicate, African-inspired percussion with Aebi’s sweet voice onto more rough-hewn terrain. A brief note by Lacy identifies Stamps as a Miles Davis homage, The Whammies as built on Fats Navarro bits and pieces, The Dumps as a rag à la Jelly Roll Morton, and so on. A honey of a salvage job. What a shame it would have been to abandon this to vinyl specialty shops! Incidentally, to see what else of Lacy’s is available, go to www.hathut.com. On to Dissonant Characters, with Ellery Eskelin, tenor saxophone, and Han Bennink, drums and suchlike [hatOLOGY 534]. Eskelin, too, is in the amelodic, free-jazz tradition, and Bennink — well, bless his heart, the man’s in his own, delectable orbit. The recording, done at Kulak, Berikon, Switzerland, in late 1988 is another Pfister masterwork. Audiophiles will wet their drawers, guaranteed. Those, that is, who listen to music as other than logs for their high-end fireplaces. There are two Monk-based numbers, Sight Unseen / Brilliant Corners and Let’s Cool One. “All compositions (unless otherwise indicated) by Ellery Eskelin and Han Bennink,” in other words, improvisations of as high-spirited, inventive a quality as it’s been this writer’s pleasure to hear. In sharpest contrast, we come to pianist Ran Blake’s Something to Live For [hatOLOGY 527], in solo, here with guitarist David “Knife” Fabris, there with Guillermo Gregorio, clarinet. Blake’s is a sound-world of misty pastel hues into which he smuggles some rather atypical moments. The word I want is painlessly. The program contains, mischievously scattered throughout, an Enigma Suite in four parts, none much longer than a minute. Here Gregorio’s contribution is obvious, as well as salubrious. When Blake operates in duo with his guitarist, we find ourselves in an easier idiom. Nineteen numbers in all, a mix of originals and spins off standards and not-so-standards. Another beautiful-sounding Art Lange production, the engineer Antonio Oliart at Boston’s WGBH studios. Finally, two discs in which the term experimental music fits comfortably and which, for me, do not succeed as recordings to rivet one’s interest. Rajesh Mehta Solos & Duos Featuring Paul Lovens / Orka, with Rajesh Mehta, trumpet, bass trumpet, hybrid trumpet and extensions; Paul Lovens, selected and unselected drums and cymbals, hatOLOGY 524. Mathias Kaul / Solo Percussion, Mathias Kaul, “percussion, cymbalon, hurdy-gurdy, bicycle, telephone, and numerous other instruments,” hat[now]ART 130.

[More Mike Silverton, Vol. 2, No. 1]

[Previous Article:

Label Report: No More Records]

[Next Article:

Incredible Risks: Improvised and New Music]

|