Label Report: NMC Recordings

|

Mike Silverton [August 1998. Originally appeared in La Folia 1:3.]

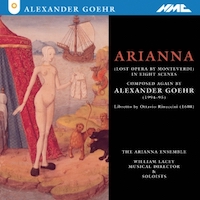

Some years ago I acquired a stack of engaging new-music discs from NMC’s then American distributor, Albany Music. Out of sight, out of mind. My interest revived recently on learning that Qualiton now distributes the once-elusive British label, about which relationship more a jiffy. NMC abbreviates New Music Cassettes. The sole format long having been the compact disc, the terminal C remains, like the human appendix, as a primeval memento. Specifically, the label began its existence as an adjunct of the Society for the Promotion of New Music (SPNM). Following its first few releases, the Holst Foundation helped fund the operation into independence. NMC operates, technically, as a charity. It certainly doesn’t comport itself like a bean-counting business — imagine keeping one’s entire catalog in print! Few record companies, including not-for-profits, trouble themselves thus. To return to Qualiton: the label joins this excellent American distributor’s roster at a propitious moment. If anything NMC lately has issued threatens to become a best-seller, it’s Arianna (Lost Opera by Monteverdi in Eight Scenes), “composed again by Alexander Goehr (1994-95), Libretto by Ottavio Rinuccini (1608),” William Lacey conducting soloists and the ad hoc Arianna Ensemble. Goehr, of course, did not pass away as a hyper-genius one-year-old. So far as I’m aware, the adult composer (b 1932) is alive and well. The years ’94-95 are of course those of his brilliant “recomposition.” The two-disc set [NMC D054] is, itself, an object to admire: fine graphics and art work, two nicely prepared booklets: the first, in English, German and French, a good and thorough background, plot summary, and bios; the second, the libretto in the original Italian and English-only translation. The recording, culled from live performances at West Road Concert Hall, Cambridge, in October, 1996, credits Tryggvi Tryggvason, Jamie Dunn and Andrew Hallifax of Modus Music as engineers. Tryggvason, whose work I’ve long admired, is here up to standard. Events transpire as exemplarily as one could ask, excepting a profoundly distorted moment on disc two. I shot off all kinds of flairs, including an email to London alerting the home office to a production glitch. In response to my urgency, a gentle question: Could I be referring to the insertion of a few moments of Kathleen Ferrier’s performance on an ancient 78 rpm disc of the famous Lament? Of course it was, surface noise and all! Shame on me for an alarmist, and yet nowhere in the notes, as good as they are, do I find mention of this smoothly integrated tribute. The libretto is interesting in that it includes sections Goehr omitted. The English text provides in brackets those characters from mythology Rinuccini’s Italian identifies but tangentially. Here, for example, is translator Patrick Boyde’s Venus in Scene One: “ the winds will blow the Theban hero [Bacchus] ” and “already the son of Atlas [Mercury], at the mouth of the fearsome cave .” Schooled as they were in the classics, Mantua’s settecento gentry needed no bracketed help. We otherwise occupied moderns need all we can get, for which, thanks. As with several of Monteverdi’s stage works, the opera disappeared, survived only by our heroine’s familiar scene-six Lament (abovementioned), which, as a hit tune, Monteverdi deployed for other occasions. Arianna has not returned in toto from the Land of the Lost. This is very much a present-day composer’s cosa sua. In contrast, for instance, with the brashly virile overture to Monteverdi’s L’Orfeo, Favola in musica, Goehr’s recreation opens on a toyshop milieu to a wash of enchanting tinkles. We are in a Never-Never Land. To have taken us elsewhere — to attempt direct re-entry into a world long gone, would have proved in the authentic doing an impossibility, or near enough to. For our comfort and delight, we require an ironic albeit loving distance that weds a Monteverdian idiom — a period feel, if you will — to an array of modernist touches, with the balance tilting to the Old, again as it must, but only so far. Excepting perhaps Stravinsky’s The Rake’s Progress (as a horse of quite another period color), I know of nothing in music so successfully done as this. We remain on classical mythology’s turf, but only in the broadest of terms. Sir Harrison Birtwhistle’s The Mask of Orpheus, Andrew Davis and Martyn Brabbins conducting vocal soloists, the BBC Singers and Symphony Orchestra [NMC D050], takes us via an attractively boxed, three-disc set to a very different world. Birtwhistle remains, thank Olympus and a will to persevere, as recidivist a Modern as British art music has to offer. (I intend Modern’s upper-case M as an indication of period placement, e.g., Romantic, Classical, Baroque, Renaissance. One makes the distinction from a dim-lit spot in history called — O hateful word! — Postmodern.) Your reporter is a Birtwhistle fan who listens in contentment to a remarkably ambitious, atmospheric work independent of Peter Zinovieff’s libretto-schematic reproduced in slipcase-miniature as a handsome 70-page booklet. In his introduction, composer Colin Matthews, who’s had an administrative hand in many to most of these NMC releases, suggests purchasing the full-size version from Universal Edition, London, as, I shouldn’t wonder, a mercy to one’s eyes, or collector’s memento. Though not, perhaps, as an aid to comprehension. A splendid story is here laden with so much symbolic freight as to render it nigh unrecognizable. And, curiously, with a quotidian deus ex machina as well: on one of several levels, the trip into hell was only a dream. So capriciously muddled do I perceive these events, I cannot say for sure that I’ve got even that right. Another booklet of 79 pages provides tri-lingual summaries (whence my insecurities), bios, etc. Heartily recommend, nevertheless, as a Birtwhistle gem. (Parlor game topic for geeks such as we: name all the composers who’ve taken on the Orpheus-in-the-underworld tale.) The other NMC release which might over time achieve best-sellerdom features Anthony Payne’s “elaboration” of Sir Edward Elgar’s unrealized Symphony No.3, Andrew Davis conducting the BBC Symphony Orchestra [NMC D053]. The rock-ribbed completist will, of course, require NMC D052, The Sketches for Symphony No.3, Andrew Davis conducting the BBC Symphony Orchestra, with pianist David Owen Norris, violinist Robert Gibbs, and Anthony Payne’s commentary. As this isn’t my thing, I’d much prefer to move on those recent NMCs that seem to me exemplars of a fine little label’s mandate. Martyn Brabbins conducts the BBC Symphony Orchestra in Michael Finnissy’s Red Earth [NMC D0405] as a “CD Single,” 19-plus minutes of music at about half-price. I’ve long been impressed via recording by Finnissy’s powerful gifts. The man does not write wimpy music. See Etcetera KTC 1091, for the hard-driving, deceptively titled English Country-Tunes, Finnissy as pianist, and KTC 1096, for three chamber pieces performed by Ensemble Exposé. See also an earlier NMC release [NMCD002], Michael Finnissy Plays Weir, Finnissy, Newman and Skempton. This tone poem — a somewhat discredited term for which I apologize and to which the composer doubtless objects — makes its intimidating entrance into our consciousness on an apparatus of astringent harmonies, largely in the upper reaches, sandwiched against a richly textured, surly low end punctuated en route by startling drum strokes. Red Earth’s soundscape is grimly grand and, to these ears, remarkably, beautifully rendered. As high as my expectations were prior to playing the disc, I was nonetheless enchanted by the music’s superb quality. In striking a judicious balance of direct to ambient sound, Engineer Mike Hatch of Floating Earth provides us with a recording we can play at a high volume setting (given a system up to the challenge) without evoking illusion-fatal artifacts. I hear Red Earth in these digs as a new-music marvel most brilliantly performed and canned. The notes to Finnissy’s NMC piano program, presumably his own, raises the subject of homosexuality as a dedicational “expression of solidarity” with a 19th-century man hounded to death for being gay. The notes to Red Earth are more direct. “Conscious of his own ‘outsider’ status as a homosexual in an intolerant England, [Finnissy] determined to study the culture of the Aborigines, equally marginalized in white Australia .” Absent these remarks, one could not possibly identify the composer as gay, straight, or out to lunch. A fine American label on a mission similar to NMC’s, Composers Recordings, Inc. (CRI), has issued several CDs of the art music of homosexuals, male and female, and so identified. I got myself in hot water in Fanfare, the bi-monthly record review for which I’ve written for a number of years, in bemoaning (intemperately, I admit) a BMG release of parallel purpose and beef-cake demeanor. Unless, as with John Corigliano’s first symphony, one intends gay agitprop, external expressions of identity politics muddy what would otherwise play as crystalline or out-of-sight, depending on one’s audience. I’m simply suggesting that Finnissy is much too good at what he does to crate himself thus parochially. The German label col legno, which I’ve also written about for this issue, sticks to a generally avant-garde path. NMC in contrast takes a uni-national tack of multi-stylistic scope. We have on the one hand Finnissy and Birtwhistle, and on the other, Robin Holloway, whose Second Concerto for Orchestra [NMC D015M — M for midlength], Oliver Knussen conducting with Stefan Ashbury’s assistance the BBC Symphony Orchestra, won a Gramophone Award for Best Contemporary Recording in 1994. Allowing for that publication’s unsubtle chauvinism, the recently released Third Concerto for Orchestra serves to further establish Holloway’s mastery. New music for large forces most often fails by way of bombast — collapsing under history’s weight into a pile of wannabe kitsch. Holloway, who surely has no fear of the Grand Romantic Statement, manipulates it with grace and skill, not to mention a consummate colorist’s palette, in the second concerto as, inter alia, a succession of amusing turns on the old pop tune, Arrivederchi, Roma. Holloway’s Third Concerto for Orchestra impresses me as the stronger. Emotionally and sculpturally, it’s a work of more ambitious scope. As much as Holloway dips into modernist technique, often quite deeply, the Third Concerto remains, as a great attraction, in the general vicinity of tonal coherence and pulse. Vaughn Williams might have been puzzled; Bartók, however, not. Nor, I think, Prokofiev. Holloway works, and successfully, on continuity’s path from the past. Which I guess is only another way of saying that one hears no trace of post-modern irony. With James Wood’s NMC release [D044], we depart art music’s core for the fringe (which, for some, is where the core should be). The program (Two Men Meet, Each Presuming the Other To Be from a Distant Planet; Phainomena; Venancio Mbande Talking with the Trees) nicely characterizes the fantasy-ceremonial quality of Wood’s handsomely textured, percussion-rich conceptions. See also Mode’s Wood disc (Mode 51, KOCH International, distributor), consisting of Village Burial with Fire and Spirit Festival with Lamentations. As I mention at the end of my col legno remarks, NMC is one of Qualiton’s import labels. Email your questions to Ron Mannarino at ron@qualiton.com. I’d take it most kindly if you told my old, albeit skeptical friend that you read about NMC here.

[More Mike Silverton, Vol. 1, No. 3]

[Previous Article:

Label Report: Wulf Weinmann’s col legno]

[Next Article:

Karajan, Carmina Mystica, Beecham]

|