Luigi Dallapiccola: For Orchestra

|

Dan Albertson [August 2005.]

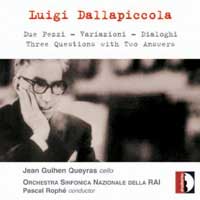

Luigi DALLAPICCOLA: Due Pezzi (1947); Variazioni (1952-54); Dialoghi (1959-60); Three Questions with Two Answers (1962-63). Jean-Guihen Queyras, cello; Orchestra Sinfonica Nazionale della RAI, Pascal Rophé (cond.). Stradivarius STR 33698 (http://www.stradivarius.it/). Were one limited to a single term for Luigi Dallapiccola’s music, I would choose enchanted. It poses a paradox: a strict structure with an emotional exterior. Call him a Romantic serialist. This disc serves as an excellent introduction to a neglected master. If he is known at all, it is likely for his choral and vocal music, including stage works. Dallapiccola’s orchestral writing shows him to be adept with large and small ensembles. The CD begins chronologically with Due Pezzi, an early work for the late-blooming Dallapiccola, written when he was 43. An orchestration of the previous year’s Due Studi for violin and piano retains the majesty (in the first movement) and rhythmic energy (in the second) of the original, here played with vigor. The contrast between the two pieces is stark and arresting. Next, an orchestration of a set of piano pieces written for Dallapiccola’s only daughter, originally titled Quaderno musicale di Annalibera. The Variazioni are in the Schoenbergian tradition: a theme a bit more than three minutes in length with ten variations, ranging from 25 seconds to two minutes, and from brass outbursts to quiet moments with the winds accompanied by celesta or soft percussion accents. This compelling piece is performed much more subtly than my introduction to it on an old LP with Max Rudolf and the Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra, owing perhaps as much to the passage of time — enough for the piece to sound less startling — as to improvements in recording technology. Written for the cellist Gaspar Cassadó, Dialoghi — this is its world-premiere recording — reflects Dallapiccola’s late style. The six years between Variazioni and Dialoghi reveal significant differences. The music is darker, with the cello fading in and out of the orchestral framework. These departures and resurgences must be the dialogues of the title, even though the conversations seldom overlap. The orchestra is large, replete with Dallapiccola’s customary coterie of saxophone, harp, celesta, vibraphone, marimba and xylorimba, to name a few of his favorites, but is used with great control. Cellist Jean-Guihen Queyras brings his typically warm sound to the piece in an interpretation meshed with more than a trace of gravitas and doubt. Three Questions with Two Answers, a work written while Dallapiccola was engaged in his final opera Ulisse, closes the program. It shares characteristics with the opera, completed five years later. Aside from some tutti, never forceful but certainly potent, this is, again, a sparse, delicately scored piece, showing to advantage the mature Dallapiccola’s restraint. The beguiling music is often awash in impressionistic formations. I especially enjoy the abundant minutiae, such as a tender, recurring and somewhat ominous pattern on a muffled snare drum. Both answers, and the second question, have their boisterous moments, with the brass applied piquantly, but contentment predominates. The final question, left unanswered, is complete bliss, a nearly static movement never above pianissimo, ending with a haze of fading attacks on celesta and vibraphone. With Dallapiccola, God is in the details, and the orchestra illustrates them with skill and understanding. Not to be missed.

[More Dan Albertson]

[More

Dallapiccola]

[Previous Article:

Kipple 1.]

[Next Article:

Repetition Isn't Always the Same]

|