Mostly Symphonies

|

Grant Chu Covell [July 2005.]

Josef TAL: Symphony No. 1 (1953); Symphony No. 2 (1960); Symphony No. 3 (1978); Hizayon Hagigi, “Festive Vision” (1959). NDR Radiophilharmonie, Israel Yinon (cond.). cpo 999 921-2 (http://www.cpo.de/). Distributed in the US by Naxos (http://www.naxos.com/). Josef TAL: Symphony No. 4 (1985); Symphony No. 5 (1991); Symphony No. 6 (1991). NDR Radiophilharmonie, Israel Yinon (cond.). cpo 999 922-2 (http://www.cpo.de/). Distributed in the US by Naxos (http://www.naxos.com/). Tal’s six tightly coiled symphonies excite like no other covered here. Collected on two discs, cpo has released Israel Yinon and the NDR Radiophilharmonie’s definitive top-drawer performances. Except for the impressionistic First, Tal’s lean atonality demonstrates an agility lacking in most symphonic cycles, 12-tone or romantic. Imagine if Berg had been a stricter serialist, but not as rigid as Babbitt. There’s a bit of Henze’s power and Varèse’s ripe invention. A master of transitions, Tal orchestrates fluently with gestures and motives well-suited to their instruments. Percussion is integral, but never overdone or showy. A one-time harp student, he uses that less prominent instrument at key structural points. Take the Second’s opening, which begins assertively with antsy strings, emphatic snare drum, harp and horns. Momentary color changes include a few solo viola notes and a brief tinkling piano and wood-block gesture. The atonal harmony changes gradually as if tumbling through permutations. Just before the one-minute mark Tal counters the tremolo and motor-rhythms with a smothering wind chord that erases the beat. It’s a masterful opening, immediately countered by a calmer second thematic area. The symphonies’ single-movement compactness encourages listening to them in sequence. The Third has a chamber-music quality, yet offers smashing climaxes like all the others. Opening with a bang, the Fourth maintains a concentrated dialog between the sweeping, agitated opening material and a probing melody introduced by strings and sax. The Fifth enters quietly, building toward string and brass collisions; great melancholy and mystery end quietly with the harp. The Sixth begins with an unusually lengthy brass statement which unwinds to include winds. Written directly after the Fifth (both were completed the same year, whereas decade-long gaps separate the others), Tal considers this a commentary upon its immediate predecessor. The last three are great music and tough going. Each single movement, flush with an alienating force, defies easy description. I suspect Tal knows the location of the abyss but skirts around it. There’s a similarity to Xenakis, whose hardened emotions formed differently. Like the Greek exile’s music, Tal’s symphonies are likely to propel unengaged listeners from the hall in droves. If you’ve ever wished minimalism and neo-romanticism had never happened, Tal is your man.

Ahmed Adnan SAYGUN: Symphony No. 3, Op. 39 (1961); Symphony No. 5, Op. 70 (1984). Staatsphilharmonie Rheinland-Pfalz, Ari Rasilainen (cond.). cpo 999 968-2 (http://www.cpo.de/). Distributed in the US by Naxos (http://www.naxos.com/). Seemingly indifferent to avant-garde trends, Saygun subtly introduced non-Western scales and rhythms into European symphonic forms. Once Bartók’s colleague on an Anatolian song-collecting trip, this Turkish composer’s elegant and finely crafted symphonies make suitable company for the elder Hungarian’s music. Ari Rasilainen and the Staatsphilharmonie Rheinland-Pfalz breeze through these scores as if they’ve known them forever. The Third’s magical opening swirls with rich colors and a dramatic use of pedal points and ostinatos. The second movement’s heralding gesture precedes free episodes framing restless, passacaglia-like sections. The hammering scherzo breathes a jazzy air, flirting with degrees of raised and lowered scales. The finale derives its heat from an organic flowing melody, contrapuntally treated. The somber Fifth gets right down to business. Saygun’s language still shows tonal roots, but the argument and development are ruthlessly compressed. The four connected movements course inevitably through dramatic pages. A whirling scherzo provides brief respite before a mysterious third-movement adagio. The finale gears up for big things, yet retreats enigmatically.

Robert KURKA: Symphony No. 2, Op. 24 (1953); Julius Caesar, Symphonic Epilogue after Shakespeare, Op. 28 (1955); Music for Orchestra, Op. 11 (1949); Serenade for Small Orchestra, Op. 25 (1954). Grant Park Orchestra, Carlos Kalmar (cond.). Cedille CDR 90000 077 (http://www.cedillerecords.org/). Distributed in the US by Qualiton (http://www.qualiton.com/). Kurka could have been a leading 20th-century American symphonist were it not for his death in 1957, ten days before his 36th birthday. His final opus, the opera The Good Soldier Schweik, was recently recorded to considerable acclaim. The opera’s suite, Kurka’s Op. 22, has been in circulation for some time. I favor Koch 3-7091-2 H1, with the Atlantic Sinfonietta under Andrew Schenck, which also provides admirable performances of Weill’s Kleine Dreigroschen Musik and Milhaud’s La Création du Monde. The earliest recorded work here, the 1949 Music for Orchestra, reveals Kurka searching for a bold, non-atonal voice, somewhere between Bartók’s Miraculous Mandarin and Ruggles. Kurka prefers minor-mode menace, as in Prokofiev and Shostakovich. He never resorts to Copland’s tablecloth-clearing sweeps, or any major-key pleasantries. It’s easy to relate Kurka to Sessions’ early symphonies or to Adams and Torke’s broad brightness. The briskly paced three-movement Second Symphony covers much ground. The first movement endeavors to remain dark and serious. Even a brief circus-like episode stays resolutely — almost perversely — minor. The sun passes over the central movement. The finale, a presto gioioso with big-city energy, syncopations and short motivic repetitions, looks ahead to minimalism. Beginning boldly, the no-nonsense Julius Caesar, Symphonic Epilogue tries to slink past, only to end in pessimistic solemnity. Kurka alternates two contrasting themes. The more angular of the two gradually grows slower and less menacing, eventually moving to the bass to become a cadence. The Serenade begins genially, with wide-leaping melodies in its outer movements. Roussel’s similarly titled work snaps to mind, the slow Adagio suggesting Prokofiev again. Carlos Kalmar’s Grant Park Orchestra plays well, handling tough string passages adroitly. High marks to the Chicago-based Cedille label for promoting a native son.

“Orchestral Works, 1944-1958.” Ingvar LIDHOLM: Toccata e canto (1944); Concerto for String Orchestra (1945/48); Three Songs (1940-45); Music for Strings (1952); Ritornell (1954). Lena Nordin (sop.); Norrköping Symphony Orchestra, Lü Jia (cond.). BIS CD 1190 (http://www.bis.se/). Distributed in the US by Qualiton (http://www.qualiton.com/). “Orchestral Works, 1958-1963.” Ingvar LIDHOLM: Mutanza (1959/65); Notturno – Canto (1958/2000); Motus-colores (1960); Riter (1959). Lena Nordin (sop.); Norrköping Symphony Orchestra, Lü Jia (cond.). BIS CD 1200 (http://www.bis.se/). Distributed in the US by Qualiton (http://www.qualiton.com/). BIS adds two more discs to its Lidholm series. We really need to hear more of this accomplished Swede’s music. The Norrköping Symphony Orchestra under Lü Jia tackles these vibrant orchestral works confidently. They better suit the band’s collective temperament than does Lidholm’s aleatoric Poesis on BIS’ first installment (BIS 1240), reviewed here. In the 1940s, Lidholm sought a distinct voice without reverting to mere imitation. His expert orchestration marries edginess to blunt seriousness. The earliest pieces, Three Songs, suggest Sibelius’ Luonnotar, with slight blushes of Grieg. Toccata e canto and the two-movement Concerto for String Orchestra impose a neo-classical stamp upon Nielsen-like swooning. The concerto’s opening Largo hints at Shostakovich. The 1952 Music for Strings leaps past the Concerto with Bartók-like cragginess. Lidholm came into his own in the 1950s. With the 1954 Ritornell he emerges, muscular and assertive, Nono-like fist raised high, with blunt contrasts and brazenly shifting colors. Ritornell’s intimate textures grow dense towards the visceral climax. The Varèsian Mutanza is acrid and robust, almost electronic. Motus-colores’ blistering outbursts strive for concision despite fidgety percussion. The ballet score Riter adds electronically manipulated voices. I’d like to see BIS repackage the three Lidholm orchestral discs together (modifying the cover art would be easy!), and set to work on the composer’s chamber music.

William SCHUMAN: Symphony No. 4 (1941); Orchestra Song (1963); Circus Overture (1944); Symphony No. 9, “Le Fosse Ardeatine” (1968). Seattle Symphony, Gerard Schwarz (cond.). Naxos 8.559254 (http://www.naxos.com/). William SCHUMAN: Symphony No. 4 (1941); Prayer in Time of War (1943); Judith (Choreographic Poem for Orchestra) (1949). The Louisville Orchestra, Robert S. Whitney, Jorge Mester (conds.). First Edition Music FECD-0011 (http://www.firsteditionmusic.com/). Distributed in the US by Naxos (http://www.naxos.com/). American symphonies like these have gone the way of cars with fins. The first installment of a Naxos series exploring Schuman delivers his Fourth and Ninth in neat, tidy performances. These well-crafted constructions, hardly avant-garde for their time yet attempting to be bold, mark Schuman’s response to WWII. Newcomers might sample this after a Copland bout; however, if one’s tastes run to Sessions or Bernstein, Schuman may prove too bland despite the obvious earnestness. Both symphonies are in three movements. The Fourth’s finale offers expertly molded variations which return full-circle to the opening’s theme. The Ninth addresses a Nazi atrocity where an entire Italian village was led to a cave and there massacred. Schuman, who strives here for hard punches, is at his best when somber emotions roll out across the orchestra. Oftentimes his fussiness stifles the flow. The Orchestra Song and Circus Overture are welcome chasers, tuneful and bright. If their titles were accidentally swapped, you would never suspect the glitch. First Edition Music reissues the Louisville’s Fourth and Prayer in Time of War, adding the five-section Judith. The Louisville Orchestra offers burnished brass in the Fourth’s 1968 recording, but the whole lacks the Seattlers’ arching scope. Prayer’s twisting emotions sound quaint, the questioning dissonance having lost its stylish bite, with war today as common as dirt. A mono recording from 1959, Judith’s programmatic pacing can easily grow tedious.

Max DEUTSCH: Der Schatz (1923; restored by Frank Strobel, 1999). Staatsphilharmonie Rheinland-Pfalz, Frank Strobel (cond.). cpo 999 925-2 (http://www.cpo.de/). Distributed in the US by Naxos (http://www.naxos.com/). Deutsch met Schoenberg in 1912 and by 1920 was the senior composer’s assistant. Der Schatz (The Treasure), G.W. Pabst’s first feature film, premiered in 1923 with Deutsch’s score. The composer fully intended his five-act “film symphony” to be self-reliant. Decades later Deutsch gave the deteriorating score to Frankfurt’s German Film Museum, and in 1999 both film and music were restored, the latter by Frank Strobel, whose dedication and perseverance warrant a salute. The Staatsphilharmonie Rheinland-Pfalz’s lively playing echoes the conductor’s evident pleasure. Don’t be thrown by Deutsch’s association with serialism’s inventor. Der Schatz’s engaging leitmotivs are more akin to Richard Strauss. It’s easy to pick out the characters: the innocent daughter, the clever assistant, the scheming villain, the greedy parents. Deutsch’s necessary responses to on-screen action required compressed thematic development, mercurial mood swings, and motivic repetition. The composer folds in plunky piano and reedy harmonium as spice to the orchestra’s 74 minutes. Descending lines might swirl like question marks, and pointed stentorian phrases glare witheringly. The several stills cpo reproduces help the mind’s eye complete the picture.

Franco ALFANO: Symphony No. 1, “Classica” (1910/18); Symphony No. 2 (1931/32). Brandenburgisches Staatsorchester Frankfurt, Israel Yinon (cond.). cpo 777 080-2 (http://www.cpo.de/). Distributed in the US by Naxos (http://www.naxos.com/). Alfano’s reputation largely rests on having completed Puccini’s Turandot. Swooning operagoers rarely notice his hand. For most, the younger Italian’s style coalesces with the master’s. (Decca B0002141-02 offers Berio’s jarring postmodern completion.) These symphonies sound nothing like Puccini, though the first reveals lyric passages redolent of the stage. Szymanowski is an obvious cousin to Alfano’s lush, dramatic First, but the orchestral palette, with its soaring string lines, solid brass counterpoints and occasional piano-plus-percussion compares with exotic Zemlinsky or storytelling Korngold. Alfano is completely his own man in the Second. The refined orchestration suggests a familiarity with Ravel. The rhythmic invention and asymmetrical structure likewise hint at a diluted Martinů or Janácek. Alfano isn’t inclined to grandstand. There’s nothing the least pompous in the “Solenne – Allegro all Marcia (pomposo)” finale. Perhaps because Alfano finished Turandot as well as he did, I find the symphonies’ conclusions inexpertly structured. While their openings’ contrasting themes build and crest, and the central movements tell romantic tales, the jocular finales don’t wrap it up. Yinon and the Brandenburgisches Staatsorchester Frankfurt dig in wholeheartedly, setting a fine standard. If you think you may have a soft spot for any of the symphonists mentioned here, then Alfano is also worth a try.

Johannes BRAHMS: Symphony No. 4 (1884/85). London Symphony Orchestra, Bernard Haitink (cond.). LSO Live LSO0057 (http://www.lso.co.uk/). Distributed in the US by Harmonia Mundi (http://www.harmoniamundi.com/). Antonín DVORÁK: Symphony No. 6 (1881). London Symphony Orchestra, Colin Davis (cond.). LSO Live LSO0059 (http://www.lso.co.uk/). Distributed in the US by Harmonia Mundi (http://www.harmoniamundi.com/). I put aside this Brahms Fourth for a cozy, rainy-day listen, but the concluding disc in Haitink’s LSO cycle disappoints. While the four movements do build to an impressive finale, the opening movement ambles flaccidly and the Andante’s second theme lacks drive. Ashkenazy’s Cleveland Orchestra recording (London 436 853-2) remains a modern fave. The energy level improves in the scherzo, timpani providing solid wallops. We have to wait for the finale’s first variation for the strings to get warmed up, but the closing pages’ pacing slams the door perfunctorily. At 41:24, there’s room for something else. By comparison, the slightly stiff but otherwise textbook-perfect Dvorák Sixth presents a satisfying 46:19. (These timings sit on the light side for CDs these days. As mitigation, LSO’s discs are generally offered at midprice.) Dvorák’s symphony bubbles gamely while Brahms’ tends towards pedantry. The first movement opens eagerly, thence to a masterful Adagio. The Sixth’s Furiant with its foot-stomping hemiola (three groups of two beats strongly accented in 3/4 time) is always a hoot, its central Trio expertly delicate. Davis delivers a relaxed finale, except at the lively breakneck coda. George Whitefield CHADWICK: Symphony No. 2, Op. 21 (1884-86); Symphonic Sketches (1895-1904). National Radio Symphony Orchestra of Ukraine, Theodore Kuchar (cond.). Naxos 8.559213 (http://www.naxos.com/). Every fan of Brahms and Dvorák’s symphonies is probably aware of Chadwick. Trained in Leipzig, he was America’s premiere symphonist before WWI. (Chadwick’s name follows Mozart, Tchaikovsky and Bizet on Boston’s Hatch Shell, the outdoor concert venue for the city’s Fourth of July concerts.) The Second matches Dvorák’s brightness and force — cultivating a European sensibility on these shores was foremost in this American’s mind. The four classically structured movements contain little ostensibly patriotic or ethnic material, such as is found in the later Ives and Copland symphonies, though the first movement stands tall, presenting its ideas neatly. The scherzo, a happy trifle, precedes a Russian-sounding somber adagio. A confident finale ties up loose ends. The Symphonic Sketches glow with quaint colors. Listening to Jubilee, you’ll imagine white picket fences and a village green. Noël is a tender adagio, Hobgoblin a light scherzo. The finale, A Vagrom Ballad, recreates a vaudeville skit chronicling a tramp’s misadventures. If anyone can help put Chadwick back in contention, it’s Naxos. Unfortunately, the National Radio Symphony Orchestra of Ukraine does only passably with the frolicsome Symphonic Sketches. Their grasp of the sober Second is insecure. This release does little to assert Chadwick’s place in the late-Romantic symphonic tradition. Why did Naxos head out to the Ukraine for this? Neeme Järvi’s Chandos recording of the Second and Third (CHAN 9685) reigns supreme.

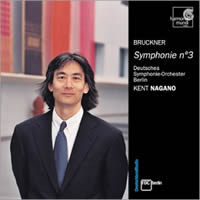

Anton BRUCKNER: Symphony No. 7 (1881-83). Orchestre des Champs-Elysées, Philippe Herreweghe (cond.). Harmonia Mundi HMC 901857 (http://www.harmoniamundi.com/). Anton BRUCKNER: Symphony No. 3, “Wagner-Symphonie” (1873). Deutsches Symphonie-Orchester Berlin, Kent Nagano (cond.). Harmonia Mundi HMC 901817 (http://www.harmoniamundi.com/). Harmonia Mundi serves up two unconventional Bruckner performances. This Seventh — a first historically informed Bruckner recording — is not a joke. The Orchestre des Champs-Elysées uses period instruments or copies. The ensemble’s string complement (13, 12, 10, 9, 7) matches the 1881 Leipzig Gewandhaus’ proportions (12, 10, 8, 8, 6). The light winds are folksier, especially in tuttis. The solo flute sounds like a penny whistle. The opening cello line is sensual; its harmonic suspensions float with a naïve delicacy. Bruckner diehards will cry foul at the bass’s skimpiness, conspicuously absent at the Adagio’s climax (no cymbal clash) and the finale’s abrupt close. Herreweghe urges us to look less heavenward. His Bruckner is a well-intentioned bumpkin, lusciously expressive and bombast-innocent. Nagano’s try at the Third, the “Wagner-Symphonie,” delivers gut-punching gravitas. Choosing Bruckner’s original 1873 edition — neither performed nor published during the composer’s lifetime — may surprise. (Naxos 8.555928/29 offers both 1877 and 1888/89 versions plus a discarded 1876 Adagio in coarse performances.) Like any modern orchestra, the Deutsches Symphonie-Orchester Berlin can go from fffff to ppp at a baton’s twitch. Such characteristic big-boned Bruckner alternates full-throttle noise with sylvan silence. Nagano is confident at the controls, but after Herreweghe’s modest, expressive efforts, Brucknerian horsepower no longer impresses. In this Third’s ticking-clock opening, I detect a little haste. On a second pass it sounded fine. Nagano opens the Adagio as if it were Schumann but soon opts for an extreme brass build-up. Lauding Stein’s Mahler Fourth reduction here, I’ve disclosed my penchant for alternate realizations. I’ve frequently queued these two discs, a heretical arrangement suggesting a dubious listening methodology. It comes down to whether you’d prefer a burger and fries from the local diner (Herreweghe) or an amply advertised meal from a chain (Nagano). There’s nothing wrong with alternating between choices.

[More Grant Chu Covell, Mostly Symphonies]

[Previous Article:

The Weiss Resurgence: 3 World Premieres]

[Next Article:

Kipple 1.]

|