Mostly Symphonies 27.

|

Grant Chu Covell [March 2015.]

Gustav MAHLER: Symphony No. 1 (1887-88; with Blumine). Hungarian National Philharmonic Orchestra, Zoltán Kocsis (cond.). Budapest Music Center BMC CD 188 (1 CD) (http://www.bmcrecords.hu/). I’ve previously expressed impatience with Mahler’s First, however, this release bucks the trend doubly. First, this 2004 live performance is bright and energetic. Second, perhaps because this is a Hungarian effort and the symphony’s five-movement incarnation originally premiered in Budapest, Kocsis restores the Blumine movement. There are moments in the Ländler (Kräftig bewegt, doch nicht zu schnell) where the propelling tempo creates anticipation. Similarly in the Funeral March (Feierlich und gemessen, ohne zu schleppen) gentle rubato adds playful effects to the Klezmer interruptions. Comparing timings against Nott and Fischer’s recent efforts (Tudor 7147 and Channel Classics CCS SA 33112), Kocsis never dawdles, properly appreciating Mahler’s frequent nicht schleppen indication. The last movement, quicksand when conductors swoon, wraps up at 17:55 (including about 50 seconds of applause). As much as it’s good to hear Blumine, the Hungarian National Philharmonic Orchestra’s proficiency makes indubitably evident that the movement Mahler eventually pulled no longer belongs. I don’t think it’s because the other four movements are so familiar, rather Blumine pales in comparison. Mahler: Symphony No. 1 (1887-88)

Gustav MAHLER: Symphony No. 2, “Resurrection” (1888-94; arr. Gilbert KAPLAN and Rob MATHES, 2013). Marlis Petersen (sop), Janina Baechle (m-sop), Wiener Singakademie, Wiener KammerOrchester, Gilbert Kaplan (cond.). Avie AV2290 (2 CDs) (http://www.avie-records.com/). The man who adores Mahler’s Second returns with an “arrangement for small orchestra.” Perhaps the transparent Fourth is a better candidate for slimming than the assertive Resurrection which wants 10 horns and 10 trumpets, two soloists, chorus and organ, and some folks to spill backstage. In the opening funeral march, Mahler’s powerful effects require a skilled army. Aside from the string complement, Mahler specifies 50 players to cover wind, brass, percussion, harp and organ parts. This reduction asks for an orchestra of 22 with onstage musicians migrating for offstage roles. Vocal soloists and chorus are still required; there are 56 musicians here in total. The Vienna Chamber Symphony appears to have been recorded in an echoing space which compensates for the modest quorum. It is possible to miss that this is dietetic Mahler, in which case we’re left with whether this interpretation convinces. Unexpected tempo changes in I and in II prompted doubling back. The two CDs simulate Mahler’s requested pause after the opening Allegro maestoso by putting the last four movements on their own disc. Those who require outsized Mahler will not be happy regardless of whether they take the time to listen. The point of this recording is to demonstrate that a pocket orchestra makes this music attainable for Schubert- and Schumann-sized ensembles. Whereas Stein’s Fourth enchants writ small, this transcription is a tougher sell. This recording was made with the forces which premiered it on February 17, 2013.

“Dvořák and America.” Joseph HOROWITZ and Michael BECKERMAN: Hiawatha Melodrama (after Dvořák, 1994-2013; arr. Angel GIL-ORDÓÑEZ, 2013)1. Antonín DVOŘÁK: Larghetto from Violin Sonatina, Op. 100 (1893)2; Humoresque No. 4 and No. 7 from Eight Humoresques, Op. 101 (1894)3; Suite in A major, Op. 98 (1894-95)4. William Arms FISHER: Goin’ Home (1922)5. Arthur FARWELL: Navajo War Dance No. 2, Op. 29 (1904)6; Pawnee Horses, Op. 20, No. 2 (1905)7; Pawnee Horses for chorus, Op. 102 (1937)8. Kevin Deas1,5 (narrator, bass-bar), Zhou Qian2 (vln), Edmund Battersby2 (pno), Benjamin Pasternack3,4,6,7 (pno), University of Texas Chamber Singers7, James Morrow7 (cond.), PostClassical Ensemble1,5, Angel Gil-Ordóñez1,5 (cond.). Naxos 8.559777 (1 CD) (http://www.naxos.com/). Antonín DVOŘÁK: Symphony No. 6, Op. 60 (1880); Suite in A major, Op. 98b, “American Suite” (1894; arr. DVOŘÁK, 1895). Luzerner Sinfonieorchester, James Gaffigan (cond.). Harmonia Mundi HMC 902188 (1 CD) (http://www.harmoniamundi.com/). Antonín DVOŘÁK: Symphony No. 8, Op. 88 (1889). Leoš JANÁČEK: Symphonic Suite from Jenufa (1896-1902; arr. Tomáš ILLE and Manfred HONECK, 2013). Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra, Manfred Honeck (cond.). Reference Recordings FR-710SACD (1 SACD) (http://www.referencerecordings.com/). Examining these three discs together, we may well wonder to what degree Dvořák influenced American music and how American music may have returned the favor. Despite a modest American tenure (1892-95), the Czech composer was clearly influenced by Native American and other tunes heard on these shores. He encouraged American composers to look to this country for inspiration as well. Contrasting Reference Recordings and Harmonia Mundi’s wares, I propose we have an American No. 8 and a Mitteleuropäische No. 6. Honeck’s Eighth is exemplary, with plenty of sunshine and warmth. Honeck’s notes suggest No. 8 is the most Czech of all Dvořák’s symphonies; however, because of that Scherzo Furiant, No. 6 really can’t be anything but Czech. Gaffigan’s last movement is energetic but light on bring-down-the-house fire, especially at the final fugato burst. Undeniably slushy, the five movements of the orchestrated American Suite could be late-entry Slavonic dances, except that Dvořák did admit to using New World ideas. On this release, they sound very European, with an emphasis on harmony over melody. Opening with assertive xylophone, the Jenufa suite proclaims an opera less pessimistic than in actuality. The excerpts tease out marvelous details. This suite begs investigating the whole opera. Naxos’ main offering is the Hiawatha Melodrama assembled from Dvořák’s music. It startles to encounter bits of the Ninth and other pieces in this context. Their union with Longfellow’s stanzas is not farfetched, and Beckerman’s argument convinces. Deas provides grand narration for what are now quaint words. The release competes with the familiar versions of content incorporated into Hiawatha and works by Fisher and Farwell which reflect Dvořák’s influence. Fisher took the second movement Largo from Dvořák’s Ninth and added a text. Farwell’s Indian-influenced works require context setting today. Enthusiastic mimicry makes up for precise transcriptions. The Navajo War Dance uses silence effectively. The two versions of Pawnee Horses (piano solo and a later choral arrangement) recalled Ornstein’s rhythms. Dvořák’s Humoresque, Op. 101, No. 7, is a staple of beginning instrumentalists. In this context the Op. 98 suite sounds very American owing to the emphasized melody.

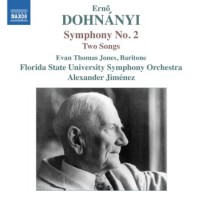

Ernő DOHNÁNYI: Symphony No. 2, Op. 40 (1945; rev. 1957); Two Songs, Op. 22 (1912)*. Evan Thomas Jones* (bar), Florida State University Symphony Orchestra, Alexander Jiménez (cond.). Naxos 8.573008 (1 CD) (http://www.naxos.com/). Dohnányi’s substantial Second suggests an earlier age, and not only because its Finale offers variations on J.S. Bach’s Komm, süsser Tod. Those comforted by Strauss and Elgar will discover a new favorite. Compared to its companions, the petite third movement Burla strikes an outré posture, as if its composer idolized Prokofiev. The earlier songs to texts by Wilhelm Conrad Gomoll, Gott and Sonnensehnsucht, are more in keeping with No. 2’s brisk Straussian style.

[More Grant Chu Covell, Mostly Symphonies]

[Previous Article:

EA Bucket 21.]

[Next Article:

Paul Bley's singular Ballads]

|