Mostly Symphonies 28: Untangling Schnittke

|

Grant Chu Covell [November 2016.] “The goal of my life is to unify serious music (Ernste Musik) We may well argue about where the border is between serious and light music, but it should be evident that Schnittke crossed that line innumerably. An inquisitive listener may grow baffled while racking up Schnittke experiences because of the contradicting stylistic jumps, often within the same piece. Examined through the prism of “The Symphony,” that Parnassus of orchestral forms, Schnittke’s efforts can bewilder as they blur the distinction between high and low, serious and light.

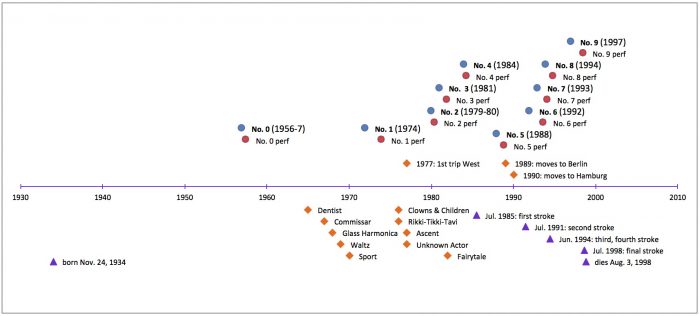

Alfred SCHNITTKE: Symphony No. 1 (1972). The USSR Ministry of Culture State Symphony Orchestra, Gennady Rozhdestvensky (cond.). Melodiya MEL CD 10 02321 (1 CD) (http://www.melody.su/). A reissue of Schnittke’s First has strolled into view, Rozhdestvensky’s first recording from 1987, and it is a necessary release for the Schnittke enthusiast. Perhaps Schnittke was wary of the symphony as a sustainable genre. I can imagine that Ives’ Fourth was consulted as an archetype, although I suspect Schnittke approached his task by being contrary. Quite possibly, getting the symphony launched was the hardest part. Schnittke’s solution was to choreograph the entrance: The piece begins as the musicians take the stage (several wander in and out during the hour-long work), some tune, the conductor appears, and soon all sorts of noise erupt. The first movement’s modern clanging, including a swipe at Beethoven’s Fifth, yields to the pseudo-Baroque ritornello of the second whose interruptions include an extended jazz ramble for violin and piano. Perhaps Schnittke wanted to write a symphony to end all symphonies, which explains the history lesson as bits of Strauss, Tchaikovsky and ragtime scuttle past. And so the epic runs all over the map, with harpsichord, electric organ, jazz trumpet, simulated crowd noise, etc., towards a finish (after several false endings) that incorporates the theatrical conclusion of Haydn’s Farewell. Schnittke started creating film scores in the 1960s. By 1984 he had contributed music to at least 60 movies. It was probably inevitable that Schnittke would write a Symphony No. 1, and one of his tactics was to reuse music he wrote for the big screen. Sometimes the recycling was a matter of practical expediency: A film might be banned but its music could be salvaged. Exploring Schnittke’s oeuvre longitudinally reveals such repurposing: The echt-Baroque fanfare from No. 1’s second movement appears in the score to Adventures of a Dentist (Gloria) and the 1972 Suite in Olden Style (Ballet). There may be other borrowings. Melodiya’s sound is coarse, but there’s plenty of edge and spontaneity. Segerstam on BIS CD 1767/68 (BIS’ reissue of Schnittke’s 10) is equally energetic, but the Russian players have the home team advantage. Rozhdestvensky’s results are also faster (64:57), or maybe there are cuts, but it’s hard to tell. This spectacle is a prime candidate for a DVD. Schnittke: Symphony No. 1 (1974)

Alfred SCHNITTKE: Symphony No. 3 (1981). Rundfunk-Sinfonieorchester Berlin, Vladimir Jurowski (cond.). Pentatone PTC 5186 485 (1 SACD) (http://www.pentatonemusic.com/). Schnittke’s Third is a “German” symphony in four movements. Orchestration and material echo Mendelssohn and Mahler; the opening explicitly recalls Das Rheingold. However, the simulation is far more complex, as the thematic material is derived from musical ciphers of German composers’ names and places. Sketches suggest a few obvious signatures: Carl Orff becomes C-A-F-F, Bach is obviously Bb-A-C-B, and Alban Berg is of course A-Bb-E-G. Other motifs are arcane, barely identifiable: Thomaskirche is rendered as B-A-Ab-Eb-C-B-E, Brahms becomes Bb-A-B-D#, Luigi Nono is but G (composers don’t have to be German, but they had to have been active in Germany). We’re probably not meant to comprehend the symbols, but Schnittke builds powerful shapes with them. Often they’re grouped chronologically or regionally, eliciting complexity and dissonance. The incorporation of electric guitar and drum set can disorient given the scope, but we must not overlook Schnittke’s dexterity in establishing and then derailing moods. The sound and heat of Jurowski’s Third easily bests Klas’ on BIS CD 1767/68. Schnittke: Symphony No. 3 (1981)

“Alfred Schnittke: Film Music Edition.” Alfred SCHNITTKE: The Story of an Unknown Actor (1976); The Commissar (1967/1987); Clowns and Children (1976); The Waltz (1969); The Glass Harmonica (1968); The Ascent (1976); The Fairytale of the Wanderings (1982-83; arr. Frank STROBEL, 2003); Rikki-Tikki-Tavi (1976; arr. STROBEL, 2003); Sport, Sport, Sport (1970; arr. STROBEL, 2003); The Adventures of a Dentist (1965; arr. STROBEL, 2003). Rundfunk-Sinfonieorchester Berlin, Frank Strobel (cond.). Capriccio C7196 (4 CDs) (http://www.capriccio.at/). These four discs present suites of Schnittke’s movie music. Strobel is credited as arranger on two of the discs, but presumably he has had a hand everywhere. By quick estimate, these 10 suites represent perhaps one-sixth of Schnittke’s film output. We may wonder whether we should consider Schnittke a concert music composer or a film scorer, but Schnittke made clear that he thought those labels were meaningless. Schnittke’s dexterity is immediately evident, as he appropriates any and all styles in order to make his points. His recycling has already been noted, and the booklet provides further examples, e.g., music from The Ascent (1976), The Tale of How Czar Peter the Great Married Off his Moor (1976), and Agony (1974-82) appears in Concerto Grosso No. 1 (1977). Outside the Soviet orbit, the films Schnittke worked on are obscure. Absent images, this music’s experience is incomplete, and so we lean on movement titles and the booklet’s synopses. I’ve seen only The Commissar (via DVD), whose straightforward plot (the Commissar waits out a pregnancy among a Jewish family) supports political and emotional complexity. Schnittke’s score responds in kind with a memorable theme for the Commissar, and several set pieces echoing Mahler’s employ of Klezmer material. Eventually Schnittke would claim some of The Commissar’s material for Symphony No. 4 (1984). Most of the suites are lighter if not whimsical. The Story of an Unknown Actor provides comic contrast to The Commissar. The Waltz contains a fluent hash of café styles and parodies. A Theremin appears in The Glass Harmonica, as well as a harpsichord, the B-A-C-H motive, and an orchestra tuning up. Disc four, with Sport, Sport, Sport and The Adventures of a Dentist is perhaps the campiest with prominent electric guitar, bongos, clear allusions to Tchaikovsky, Francis Lai, Mancini, Morricone, and Sato’s scores for Kurosawa. As mentioned before, Dentist has music that reappeared in Symphony No. 1 and the Suite in Olden Style. The Fairytale of the Wanderings is the latest score on offer. As a suite, it has less punch than the others. It borrows bits of accompaniment and instrumentation heard in Sport, Sport, Sport, and I think it shares moments with Rikki-Tikki-Tavi on the same disc. I am confident there are other borrowings across these suites which have escaped me, just as there’s material that appears in the symphonies.

Alfred SCHNITTKE: Penitential Psalms (1988); Three Sacred Hymns (1983). RIAS Kammerchor, Hans-Christoph Rademann (cond.). Harmonia Mundi HMC 902225 (1 CD) (http://www.harmoniamundi.com/). Schnittke’s film production appears to have dwindled after the first of several devastating strokes (July 1985) and stopped completely after his move to Berlin (1989). Starting in the late ’80s, he set aside the tendency to play up contradictions and stylistic incongruities and became more earnest. The 12 Penitential Psalms are among Schnittke’s most somber compositions. I have admitted elsewhere that choral music strains my understanding, but I appreciate this music’s austerity, devotion, and expression of craft. This sequence of 12 a cappella pieces with 16th-century texts was written in 1988 to commemorate Christian Russia’s 1000th year. Firmly modern, powerfully chromatic but not gratuitously dissonant, these Psalms are mindful of the preceding Russian tradition. There might be an unexpected slide, or a phrase resolving uncomfortably long on a minor second. Men and women’s voices are alternated and combined to underscore the text and provide dramatic continuity. The last movement is hummed. The RIAS Kammerchor provides impeccable intonation and velvety balance. The disc and movement titles are in German even though the Psalms are in Russian, a smooth and softened Russian which made me momentarily wonder whether the language was actually German. For a full 48 minutes, there’s nothing ambiguous here, nothing that suggests its composer could command many styles and would with apparent frivolity combine them in the same work. The three Hymns are simpler filler (about six-and-a-half minutes in sequence), closer to the Russian tonal tradition. They were written in a single day to fulfill a persistent request.

[More Grant Chu Covell, Mostly Symphonies]

[More

Schnittke]

[Previous Article:

In 1908...]

|