Mostly Symphonies 29: Keep Going, Keep Going… Two new Berio Sinfonias

|

Grant Chu Covell [November 2016.]

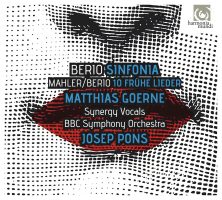

Gustav MAHLER: 10 Frühe Lieder (1884-85; arr. Luciano BERIO, 1986-87)1. Luciano BERIO: Sinfonia (1968-69)2. Matthias Goerne1 (bar), The Synergy Vocals2, BBC Symphony Orchestra1,2, Josep Pons1,2 (cond.). Harmonia Mundi HMC 902180 (1 CD) (http://www.harmoniamundi.com/). Luciano BERIO: Quattro version orginali della Ritirata Notturna di Madrid di L. Boccherini (1975)1; Calmo (1974; rev. 1988-89)2; Sinfonia (1968-69)3. Virpi Räisänen1 (m-sop), Sinfonia3: Mirjam Solomon, Annika Fuhrmann (sop), Jutta Seppinen, Pasi Hyökki (alt), Simo Mäkinen, Paavo Hyökki (ten), Taavi Oramo, Sampo Haapaniemi (bass), Finnish Radio Symphony Orchestra1,2,3, Hannu Lintu1,2,3 (cond.). Ondine ODE 1227-5 (1 SACD) (http://www.ondine.net/). Berio the finisher (Puccini, Schubert, et al.) and arranger (Verdi, Brahms, himself, et al.) was asked to orchestrate several Mahler songs from Des Knaben Wunderhorn. Mahler had already reused several of these songs in his own music, and Berio’s treatment reflects this, generally adhering to Mahler’s style ca. Kindertotenlieder. Given his experience with Schubert, Goerne is perfectly at ease in these settings, which leads to the inevitable question: When will he record Lieder eines fahrenden Gesellen and Kindertotenlieder? Knowing Sinfonia lurks around the corner, these songs take on an innocent, even archaic quality, especially in the jolly outbursts of Hans und Grete, quaint when we know the postmodern age is just moments away. Ondine offers a “Welcome to Berio” program sequencing three representative works. Considering the Ritirata and the Sinfonia together suggest that Berio was a composer of layers, habitually stacking different music and discovering similarities. The Ritirata does this explicitly, superimposing Boccherini’s four versions of the same piece. Berio contributed no new notes, merely the alignment. Like the procession it describes, the tune comes into view, then retreats, repeating all the while. A Classical Bolero, its six-and-a-half minutes make a nice concert opener. Calmo was written after the death of Bruno Maderna, the Italian conductor / composer key to the education of Berio, Nono, et al. Berio was continually reconsidering, reshaping his own works, expanding them with more players and second endings, and this version of Calmo is scored for a predominantly wind ensemble, with percussion and a few violas, cellos and basses. Texts include anonymous Greek lyrics, Homer, Edoardo Sanguineti, Saadi and the Bible. Calmo establishes Berio’s skill in orchestration. The winds suggest Messiaen, though there are Boulezian outbursts and colors presaging Murail and Grisey. Layers and revisions come to the fore in Sinfonia, perhaps Berio’s most famous, or most examined, opus. The second movement, O King, orchestrates an earlier, smaller setting. (Someday, I’ll take the time to explore whether this memorial to Martin Luther King reflects Dallapiccola or Nono’s political works.) Berio added the fifth movement after the premiere, creating a final statement which repeats and summarizes content from the prior four movements. Inevitably, we are drawn to the central section, which appropriates the third movement, In ruhig fließender Bewegung, of Mahler’s Second Symphony, upon which Berio folds dozens of musical quotations triggered by the declaimed texts (Mahler himself borrowed from Bruckner, Beethoven and Schumann in his original). One class of listener will consider the myriad allusions a code needing to be cracked, others will think it tedious. Sinfonia’s four-movement version was premiered Oct. 10, 1968, by the New York Philharmonic under its composer’s direction. The fifth movement was ready for a performance in Donaueschingen on Oct. 18, 1969. Eight vocalists join a large orchestra enriched with saxophones, electric organ, and violins separated into three groups rather than the customary two. Texts are drawn from Claude Lévi-Strauss and Samuel Beckett, in addition to slogans Berio saw and heard firsthand during the mid-’60s student uprisings. English and French are the most common languages. The octet doesn’t just sing, it chatters and talks over the music in a way that must have initially shocked. The eight open the piece with a sung chord, but quickly break loose into warbling and talking until the orchestra levels the ground with a blasting chord. Previous works with eight soloists include Mahler’s Eighth and Verdi’s Requiem, but in this case, Andriessen had been studying with Berio and had shared with him an LP featuring the eight-person Swingle Singers who were then asked to take part in Sinfonia’s premiere. As a pretentious composition student, I relished the quotation identification game. Today, even with the score at hand and knowing the verbal cues, I have trouble perceiving the Hindemith, Pousseur and Stockhausen. These days I spend more time admiring the outer movements’ details and Berio’s instrumentation skills. Even with the reflective, summarizing fifth movement, the entire work doesn’t resolve conclusively. Bits of the prior four movements, quotes and all, swirl and build to a finely crafted climax, and we exit the piece as if startled out of a dream. Art is messy, and we can’t create something new without referencing the past. A lot of people don’t hear it this way because the central movement, a pastiche par excellence, gets all the attention. Both Pons and Lintu let the electronic organ and harp play out. Pons and the BBC are crisper in the outbursts, especially in I. For whatever reason, perhaps because Boulez died this year, I was attuned to Don’s opening chord, swiped from Boulez’s Pli selon pli. It startles wonderfully under Pons, whereas it’s not tuned under Lintu, as if the allusion is unfamiliar. For just this one chord, the BBC has a small advantage as they’ve played and recorded Pli selon pli. In both recordings Schoenberg’s Peripetie sounds energized, and I wonder if that’s because Berio begins the third movement with it whereas in Schoenberg’s Op. 16, the orchestra is already tired by the time it comes around in the fourth piece. Considering the balances between the voices and the orchestra, both groups are intelligible, although neither is as fully cohesive as the London Voices were in Eötvös’ 2004 recording (with the Göteborgs Symfoniker on DG 00289 477 538-0). As to be expected, the New Swingle Singers, with Ward Swingle himself as Tenor I, remain the most theatrical octet (under Boulez, with the Orchestre National de France on Erato 2292-45228-2), but either of these newer recordings has better balance and reveals more details. The newcomer to Berio can benefit from Lintu’s program, whereas the Mahler fan and perhaps the Sinfonia enthusiast ought to prefer Pons. Luciano Berio: Sinfonia (1968-69)

[More Grant Chu Covell, Mostly Symphonies]

[Previous Article:

Mostly Symphonies 28: Untangling Schnittke]

[Next Article:

Mostly Symphonies 30.]

|