Music in the Midst of the Plague: A Conversation with Beth Levin

|

Gil Reavill [August 2020.]

GIL REAVILL: I assume you’re in quarantine along with the rest of us. How have the months of isolation influenced your creativity, or, on a more commonplace level, changed your practice routines? BETH LEVIN: I’m not sure. Everything is different — that much I know. I’ve been working on music that I would have performed in the spring and summer, specifically Schumann, Chopin, Beethoven and Yehudi Wyner. But I notice that I’m approaching it in ways that match the longer road we’re on — taking time to pull things apart, to muse, to examine voices and phrasing and only then putting the pieces back together. Even in the most presto passages now there seems to be an inherent slowness. I was always saying things like, “I wish I had a year to learn that concerto,” or, “I wish I had two years for that set of variations.” “The pandemic is a portal,” states novelist/activist Arundhati Roy. Do you find it so? Perhaps it is an inward portal. One’s creativity really can be nurtured right now because we are in a blank state, with nothing pressing, nothing other than music and time. I’m amazed at how much emotion rises up as I practice — nothing is there to stop it. Also, I’m looking back, perhaps too much. I’ve put many old performances on Soundcloud and listening has been cathartic. This passage from T.S. Eliot’s Four Quartets came to mind: The river is within us, the sea is all about us;

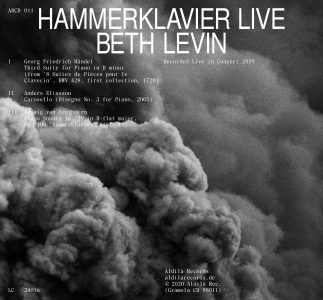

By the time this interview appears, your recording of Beethoven’s Hammerklavier will be out. You seem to be attracted to tremendously challenging works, and have recorded The Goldberg Variations and The Diabelli Variations, to mention only two. Well, first, that’s a tradition from my teachers, particularly Shure and Serkin. And I like works that are made up of variations such as the Goldbergs, Davidsbündlertänze, the Schumann Symphonic Etudes, Diabelli, etc. I have never let not being able to play something stop me from learning a new work — ha-ha! Honestly, I have friends who won’t play this or that because of a large stretch or a fiendish page or two. If a work has a great and true expressive quality (practically anything of Schumann, say), but is technically challenging, expression wins out.

I’m interested to know the ways in which the emotional tenor of a work such as the Hammerklavier might change in the run-up to performing it in concert or preparing for a recording, shifting with the player’s increasing facility, familiarity, or understanding. I find closer to a performance that the whole endeavor seems utterly impossible. I felt that way with the Hammerklavier even after months working on it. I mean you have good days when you feel that there is hope and everything is coming together. Just that fact of making Op. 106 feel like one piece is quite a challenge. Thinking in the longest lines possible helped, and not being afraid of glacially slow or impossibly fast. The dynamic range asked for was also exciting in its scope. There is an ecstatic aspect to the sonata that may only be truly realized on stage. I think you can understand aspects of the Hammerklavier, be familiar with it and even have the facility to play it well — but the work has its secrets. I think in the end you play it to see where it will take you and take the audience.

You write poetry. What sort of cross-fertilization do you detect between language and music? The ear and one’s sense of pulse has so much to do with both language and music. Especially if you read a poem aloud — you can hear how the pure sound of the words has a musical and rhythmic basis. I’m quite an amateur poet and never feel I know what I’m doing. I’m pretty seasoned as a pianist, and a novice at poetry writing. But my musicianship does help me as I write a poem. This strange pandemic seems perfect for using time in creative ways and in ways we might not try otherwise. You’ve had a long association with the works of Robert Schumann, recording Kreisleriana and performing other works, and have also written about him recently. How do you engage with Schumann as a composer and creative force? I probably have an affinity for composers who don’t want to be tied down, completely understood or caught. When I think of Schumann, I think of someone reaching upward, yearning, seeking and with an ardent intensity. And I think of ultimate contrast. As soon as you meet Florestan and Eusebius in his writing, you experience Schumann’s own extreme dual nature. Schumann loved words as well — see his writings in Die Neue Zeitschrift für Musik. I was given the music of Schumann as a child and am still discovering it. Most recently I performed the Piano Trio in D minor with Roberta Cooper and Eugene Drucker and currently I’m working on the Symphonic Etudes for piano. His music is uncannily intimate and so on that level it is very easy to engage with it. On the other hand, Schumann strove to write orchestrally for the piano and wound up writing some deliciously hard music for the instrument. Schumann wrote fondly of Clara’s performance: “The way you played my Etudes — I won’t ever forget that; they were absolute masterpieces the way you presented them — the public can’t appreciate such playing — but one person was sitting there, no matter how much his heart was pounding with other feelings, my entire being at that instant bowed down before you as an artist.”

There’s been some back and forth of late about whether Bach’s Well-Tempered Clavier was written for harpsichord or clavichord. With cellist Samuel Magill, you’ve performed preludes from the piece, arranged by the virtuoso Ignaz Moscheles. Any thoughts on period instruments versus their modern offspring? The music of Bach has that ability to survive just about any treatment and still emerge as Bach. When I first saw the Moscheles transcription the word “schlock” may have crossed my mind. But Sam won me over with his gorgeous playing and love of Romanticism. I believe we began the program with the Bach and after the concert it was one of the most remarked upon works.

You often perform and record contemporary composers. Do you seek out connections, comparisons, commonality, or inheritances in earlier works of the Baroque, Classical, Romantic or Modern canon? Some of the contemporary music I’ve played seems to spring very naturally from earlier periods — say, the music of David del Tredici, Yehudi Wyner or Scott Wheeler. Other works break off from tradition completely. Bunita Marcus comes to mind. Lately I’ve been sending little music notebooks to composer friends and one, Frank Brickle, has begun writing me pieces for piano. I can’t wait to see the result. I think as in more traditional music you have to find the voice of the work itself and not make comparison studies. [Photos by Beth Levin and Gary Chapman.]

[More Beth Levin, Gil Reavill]

[Previous Article:

String Theory 32: Quartets, plus or minus]

|