Observations on the Hammerklavier Slow Movement

|

Beth Levin [November 2017.]

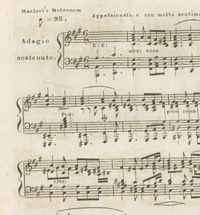

Adagio sostenuto Beethoven’s Hammerklavier sonata as a whole, and its third movement in particular, has always elicited mournful superlatives from commentators. Musicologist Wilhelm von Lenz famously characterized the Adagio as a “mausoleum of collective sorrow,” while composer, author and classical scholar Jan Swafford writes of “spinning roulades like streams of tears,” and terms the third movement “a sublime performance of sorrow and transcendence by a singer who has known every shade of grief and hope.” “Passionate and with great feeling,” indeed. For the player, the Adagio poses both emotional and pianistic challenges, which begin instantly with the opening. Rather than start squarely on the theme, Beethoven offers as introduction two slow dotted quarters, A to the third above, C-sharp. Swafford provides some background: “Beethoven sent the H’klavier to Ries in England, then a while later sent the opening bar to add to it. Ries thought his old teacher had gone round the bend — until he played it. It’s a simple statement of thirds, which underlie the whole piece in myriad ways, but it’s also a kind of elemental introduction to a sublime movement.” The melody itself is an exquisite, heartfelt, soul-bending utterance in F-sharp minor with rich chordal accompaniment. I admire how Beethoven varies the density of his chords, so that some are composed of a few notes and others stretch out over the range of voices. At measures 13-14 the dark harmony suddenly melts into G major via a diminished chord. I have written “dreamy” and “clarinet” in my score, but I might as well have copied a sonnet of Keats. The G major bars peek out like a row of poppies waving in a meadow on a cloudless day. Beethoven performs a similar adroit shift at measure 23. The two bars in major hint at an improbable happiness, and one that is fleeting. With notations of “tutte le corde” and “con grand espressione,” the composer begins to transform the once languid melody. At measure 27 he adds a punchy bass line against syncopated notes, playing off of a theme which has been turned upside down and inside out. Triplets, running 32nds, and trills embellish melodic notes and the dynamic markings give a sense of the music’s form, suggesting places to hold back, to dance, and to introduce rubato. It’s Fellini reinterpreting Bergman. Measure 39 is another departure from the minor (I’ve written “deep river” in my score), with liquid 16ths that move like slow turns and create a temporary haven of calm. At measure 45, Tempo I, the fleur-de-lis pattern moves to the bass. The treble or right hand notes alternately dip, then reach to the skies in counterpoint to the legato turns. A pianist friend told me that he once performed the third movement at a very slow tempo and someone in the audience snored loudly through it — a kind of criticism that is hard to argue with! Beethoven repeats the initial ideas of the movement and then takes his time, basking in them. As Clara Schumann once wrote in a different context, “Why hurry over beautiful things? Why not linger and enjoy them?” Throughout the entire Hammerklavier sonata, one senses his limitless creative powers, perhaps imbued with the intent of an artist writing the definitive fugue, or the definitive work in sonata form; a “once and for all” quality that cries out from the pages. The third movement is no exception to that, and a performer does have to choose a tempo in consideration of its length. In fact, choice of tempo is crucial to the performance. I think differences in texture and emotional states, the contrast of dynamics and color, and moments of rubato are all inherent qualities of the third movement and can be brought to life with a little luck. In bars 69-84 the opening theme works as a transition, entering new keys, with odd notes being accentuated by sforzandi, but eventually everything dissolves back into F-sharp minor. So at measure 87 (poco apoco due e lora tutte le corde), the theme is a mere outline in the midst of a pattern of 32nd notes in the treble; the bass composed of chords on each eighth beat of 6/8. The effect is a haunting, expressive beauty highlighted by two-note passing tones in the treble, heightening the sad, urgent and unresolved quality of the music. Approaching measure 113, we realize that the material ahead will be a recapitulation of everything that came before. Major and minor are sometimes interchanged, the lines are more highly embellished with tiny fast notes, and the dynamics are even more expressive, seeming to outline form as well as a sound palette. Beethoven comes to the end by restating the devastating opening theme, accentuating a diminished chord for a mere moment, then resolving to glorious chords in F-sharp major. Such a hopeful ending foretells the exquisite nature of the movement to come.

[More Beth Levin]

[More

Beethoven]

[Previous Article:

Mostly Symphonies 31.]

[Next Article:

Mostly Symphonies 32.]

|