On Schumann’s Davidsbündlertänze (II)

|

Beth Levin [April 2002.]

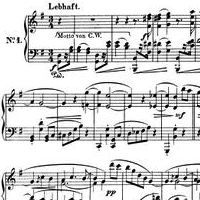

On Schumann’s Davidsbündlertänze. Book I. Book II 1. Sehr rasch (Very fast) Book II begins with a powerful dance in D-minor. The melody spans both hands at the piano, beginning in octaves in the bass, continuing in the middle voice and coming to completion in the treble. Every note of the melody is marked with a sforzando, which lends richness and a sense of drive to the line. Triplets play in and around the melodic notes. Here Schumann is a master tailor weaving together diverse elements — melody, accompaniment, dynamic expression, shape, timing — elements that infuse a ballade in 3/4 with imagination and strength. The finished garment is an inventive tapestry, rich in detail, silver threads and fine nobility. 2. Einfach (Simple) After a fermata the ensuing dance is slow, which continues Schumann’s pattern of a frenetic dance followed by an intimate one — the struggle between Florestan and Eusebius. The first note, a B, is tied over the bar line to a B-minor chord as it begins a soulful melody. The effect of the tied note is poignant and subtler than beginning the melody smack on the downbeat. It is a bit like a great writer who opens a short story with a tiny detail that gains in significance and finally becomes critical to the story. So here, the opening tied note forms a pattern for the slow dance, pulls at us and at the melody to move ahead, deterred only by the heaviness of the chords present in the melody. As in Bach, there is nothing that can be construed as accompaniment. Both hands double the melody or provide important counterpoint to each other. 3. Mit humor Again (as in Book I) the elements of ballet and the circus are felt. The bass is composed of leaps worthy of any Fats Waller tune. The performer relies on an intuitive sense of the keyboard and a legato touch to span the leaps with confidence. The feeling must be one of abandon, energy — the high wire. Nothing could be worse than for the performer to play it safe. Schumann gives the effect of bells in his use of quick, light 32nd notes, while the staccato notes and accents achieve the physical sense of leaping and landing gracefully. The resulting joy and humor relieve some of the sadness of the previous dance. 4. Wild und lustig (Wild and gay) Fortissimo chords, octaves and speed make this a wild and passionate dance. The key of B-minor takes on a different meaning for the music than in the second dance of Book II. No longer inwardly brooding, B-minor becomes more heroic, powerful, robust. Then, suddenly, Schumann turns the music inside out to the key of B-major. The color change is stark. There is no ritardando to ease the transition for the listener. The surprise of B-major, that unexpected stroke, is exactly what moves us. The music simply melts into B-major from the minor and I often think it is a mistake to set up such a moment. Letting it happen is the best choice. The end of the dance has a reminiscing quality, one of looking back over the drama of the work and coming to a temporary peace. It is in such music that one wonders if art and life do reflect one another, if Schumann may have drawn from life and his own sense of truth. 5. Zart und singend (Delicate and singing) This may be the tenderest moment of the work. The melody is heartbreaking, simple and beautiful. The accompaniment reminds one of Chopin, another composer Schumann loved and paid tribute to in his writing. A small coda in pianissimo is another comment on the piece itself — affirmation, release, resignation. 6. Frisch (Fresh) The robust introductory eight measures are repeated at the end, thus framing the main body of the dance. A clear song accompanied by a bass of arpeggios gives this writing a romantic sweep. The key of E-flat suggests a love song and a melody infused with passion. When the melody shifts to the bass line, Schumann achieves a sense of the orchestral scope so inherent in his composition. The more the performer can imagine different timbre and color and broaden the sound world at the piano, the closer he or she will come to entering Schumann’s imagination. Pianists love to play Schumann precisely because his writing can alter one’s experience as a musician, suggest new paths, and extend one’s palette of sound by creating a desire for something more. 7. Mit gutem humor (With good humor) This dance feels like the beginning of the end — a transitory dance leading us to the finale. It is all staccato chords — running, mercurial and illusory. First in G-major and then in B-minor, the chords transform from playful to poignant. In general Schumann likes to keep us guessing, always suggesting another mood, a new character, a different emotion waiting round the bend. He rarely lingers in a single place for very long. The dances have exhausted us; when we reach the finale we are relieved and desire a sense of peace and resolution. 8. Wie aus der Ferne (From a distance) All the calm of a green meadow is heard now, as if the balance and harmony of nature were being expressed through Schumann’s melodies. The chords are steady and gently pulsing. It is in this way that we are led back to the second dance of Book I. This restatement is another of those critical places in the music that needs to be handled just right. Too much of a ritardando before the re-entry of the theme can be ruinous. A combination of subtle timing and exquisite color change may result in one of the most moving moments in the entire work. After restating the beauty of the dance Schumann transforms it, letting it spin out of control, faster and faster, until it erupts in a display of octaves and broken chords. Then it is a quick descent from frenzy to an exhausted final chord in B-minor. The range of physical qualities in Schumann’s writing is massive here, suggesting extremes of motion from wild speed to inertia. 9. Nicht schnell (Not fast) The coda in C-major feels like an objective commentary on all that has gone before. There is the wry quality of a character walking away, creating distance between himself and any emotional involvement he may have felt. Small two-note slurs stroll along the page, become softer and more remote, and end in three C-major chords coming off a low bass note C. The three chords sound like three bells tolling. And so the great work comes to an end, not in grand chords or flourishes but in three stark peals of sound. This is a perfect ending as inevitable as death — a release from it all, a final sigh of beauty. [Beth has supplied a terrific map of the piece. I started with Perahia’s 1973 reading (Sony MK 32299) before moving on, and back, to Cortot and Gieseking. – – W.M.] [More Beth Levin]

[More

Schumann]

[Previous Article:

On Schumann's Davidsbündlertänze (I)]

[Next Article:

Playing in Tongues: New and Improvised Music]

|