Piano Factory 26.

|

Grant Chu Covell [April 2020.]

André RIOTTE: Météorite et ses métamorphoses (2000-01). Thérèse Malengreau (pno). Grand Piano GP679 (1 CD) (http://www.grandpianorecords.com/). With a blunt motif, 31 variations and a coda, Riotte’s Météorite et ses métamorphoses establishes itself as a concentrated chain of modernist miniatures. These are unyielding pieces, not a linear series of variations, but a group that unfolds through formalist exploration and intuition. The theme, Météorite: Massif, came to the composer all at once, “a tranquil block fallen to earth from some obscure disaster.” Météorite reflects mutations in the physical world and less tangible cosmic relationships. André Riotte (1928-2011) studied with Honegger, Messiaen and Jolivet. He worked with Xenakis at CEMAMu and lectured at IRCAM. Like Xenakis, composition was but one aspect of his education and career: Riotte was an electronics engineer and worked for the European Commission at the Joint Research Center in Ispra, Italy, managing a data-processing lab. These uncompromising pieces pass quickly, revealing similarities to Messiaen (modal and specific harmonies), Boulez (colors spanning the piano’s full compass) and Barraqué (compact severity). Météorite is dedicated to Xenakis, and Malengreau premiered it in 2002. The 31 metamorphoses pass through Boulezian whorls (VII: En volutes), hammered rhythms (XIV: Staccato vif et vigoreux), rhapsody (XXV: Recueilli), several untitled movements (I, IX and XVII), and sterility (XXIX: Enigmatique et sans espoir, extremement lent). Several are less than a minute; XXXI is the longest and an unexpected multipart culmination. The concluding Coda (Lent et solennel) wraps up as a stern processional.

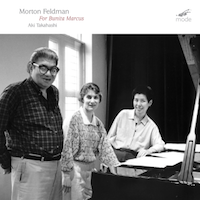

“Feldman Edition 13.” Morton FELDMAN: For Bunita Marcus (1985). Aki Takahashi (pno). mode 314 (1 CD) (http://www.moderecords.com/). Listen to Feldman’s Coptic Light (1986) and hear an orchestra shuffling short motifs like a cranky sorting machine at the post office. There’s repetition among similarly sized items, but the motion is efficient. Feldman’s solo piano works are lean. Imagine hushed single notes (a one-fingered pianist) with pedal down. Others (for example Liatsou and Hamelin discussed here) proceed delicately as if aligning Feldman with Satie, describing matched porcelain tea sets while rain falls gently. This approach is reasonable because For Bunita Marcus is 75 minutes long and pacing is crucial. Takahashi knows Feldman better than most. She has been playing this piece since its 1985 premiere. (That’s her with the composer and dedicatee on the cover.) This For Bunita Marcus is not precious, not atmospheric. There is no small talk, no interest in the weather. From the opening repeated notes (repeating notes in Feldman?!) we get purpose, perhaps with a greater dynamic gamut than indicated. Those bright unexpected arpeggios which elsewhere I described as a lightning strike pass matter-of-factly with unaccustomed weight. Late Feldman is about density, memory, sound and time, and other vast imponderables, however Takahashi offers notes that slice assertively. Maybe For Bunita Marcus is just an etude built from 3/8, 5/16, 3/4 and 2/2 measures thwarting a grid. We’re going to get somewhere, but not right away. Although, when we do, the last pages with slow chords are magisterial.

“Complete Piano Works.” Toivo KUULA: Three Piano Pieces, Op. 3b (1906-08); Two Song Transcriptions, Op. 37 (1917); Air varié (ca. 1900); Invention (ca. 1905); Old Autumn Song, Op. 24, No. 3 (1913); Schottis (ca. 1904); Festive March, Op. 13b (ca. 1910); Six Piano Pieces, Op. 26 (1914-16); Lampaanpolska (1915); Three Fairy-Tale Pictures, Op. 19 (1912). Janne Oksanen (pno). Alba ABCD 445 (1 CD) (http://www.alba.fi/). “Complete Works for Solo Piano.” Toivo KUULA: Three Folk-Tale Pictures, Op. 19 (1912); Three Piano Pieces, Op. 3b (1906-08); Festive March, Op. 13b (1910); Lampaanpolska (1915); Air varié (ca. 1900); Schottis (ca. 1904); Six Piano Pieces, Op. 26 (1913-16); Two Song Transcriptions, Op. 37 (1917); An Old Autumn Song, Op. 24, No. 3b (1913); Invention (ca. 1905). Adam Johnson (pno). Grand Piano GP780 (1 CD) (http://www.grandpianorecords.com/). A student of Sibelius, Toivo Kuula (1883-1918) wrote meltingly lyrical music akin to Grieg and Tchaikovsky (think of the Letter Scene in Eugene Onegin). Kuula’s melodies sound familiar and his tunes are eminently singable. They are also bittersweet, suggesting that beyond the pleasantness (Wedding March, Schottis, etc.) there lurk strong passions. Indeed, these could be performed as trifles or with Romantic fervor, but the suggestion that Sibelius was nearby justifiably tempers enthusiasm and encourages a deeper look. The longest piece is the Festive March (Juhlamarssi) which also exists in a version for orchestra. The gradually intensifying Lampaanpolska (“Mutton Dance”) utilizes the La Folia theme. Nocturne, Op. 26, No. 4, edges towards Scriabin with quartal harmonies and comfort with the tritone. Oksanen and Johnson strike different paths. Johnson plants Kuula solidly in Romantic territory which unfortunately makes the music sound ordinary; the Folk-Tale Pictures lean towards Debussy. On the other hand, Oksanen is brisk and impetuous, not concerned with making this music sound like others. With Johnson, the three early pieces are thick, however with Oksanen they are magical.

“Complete works for solo piano.” Artur SCHNABEL: Three Fantasy Pieces (1898); Three Pieces, Op. 15 (1906); Dance Suite (1920-21); Sonata (1923); Piece in Seven Movements (1936-37); Seven Piano Pieces (1947). Josef STRAUSS: Four Waltzes from Old Vienna (arr. SCHNABEL, 1908). Jenny Lin (pno). Steinway & Sons STNS30074 (2 CDs) (https://www.steinway.com/music-and-artists/label). A complete edition of Schnabel’s piano music is long overdue. Lin has seized upon a great opportunity. The showpiece collection, Three Fantasy Pieces, written when Schnabel was 16, represent a precocious piano student, then studying with Leschetizky. Schnabel’s musical personality developed quickly, although indifferent to models: The Op. 15 group exhibits a secure grasp of late-Romantic tonality with curious whole-tone and other harmonic detours. The Three Pieces deliver more than titled as No. 3 is a sequence of four crisp waltzes. Schnabel’s devil-may-care attitude is evident in the extroverted Dance Suite which evolves from a foxtrot through abstraction into impetuous hypertonality. The movement titles describe a possible tryst: “Foxtrot (Encounter),” “First Pause (Wooing),” “Waltz (Contact),” “Second Pause (Floating)” and “Towards Tomorrow (Affirmation).” Schnabel appears to have favored multi-movement encounters. There are five movements in the Sonata and the later collections have seven movements each. The Piece in Seven Movements could have been a “Sonata,” and the Sonata could be a “Piece in Five Movements.” The meticulously detailed Sonata splashes wildly, unabashedly dissonant and heroic. The Fantasy Pieces’ virtuosity has become atonal Busoni. Toscanini’s wonderful comment bears repeating: “Are you really the same Schnabel who wrote that horrible music I heard ten years ago in Venice?” (The conductor had been at the 1925 premiere.) The Piece in Seven Movements combines Schoenbergian dryness with neo-classical playfulness. Recall that Schnabel (1882-1951) was born in the same vicinity as Webern and Berg (1883 and 1885), and that he died the same year as Schoenberg. The Seven Pieces are on the shorter side, displaying brittle intensity with false endings. No. 3, Andantino, is a compact, vivacious dance suggesting that Schnabel would have a been a fine Schoenberg interpreter. The evidence implies Schnabel loved waltzes: We have the third Fantasy Piece, the sequence concluding Op. 15, the Dance Suite’s central movement, the initial theme group of the Sonata’s conclusion, the Vivacissimo from Piece in Seven Movements, and the piano elaboration of several Josef Strauss waltzes.

“Brahms the Progressive.” Johannes BRAHMS: Klavierstücke, Op. 118 (1893); Klavierstücke, Op. 119 (1893). Anton WEBERN: Kinderstück (1924); Satz für Klavier (1906); Klavierstück – Im Tempo eines Menuetts (1925); Variations, Op. 27 (1936). Alban BERG: Sonata, Op. 1 (1907-08). Pina Napolitano (pno). Odradek ODRCD330 (1 CD) (http://www.odradek-records.com/). Would that Berg and Webern sandwich every Brahms program. There is little distance between Brahms’ Op. 119, No. 1, Webern’s 1906 Satz and Berg’s Sonata. Webern and Berg strayed away from the all-powerful octave whereas Brahms remained steadfastly within. What if Brahms hadn’t felt obliged to return to his starting point? Napolitano reflects Brahms’ “miraculous equilibrium,” in that Brahms looks back to Beethoven and Bach, but also forward as Schoenberg observed in the 1933 essay which provides this release’s title. Certainly, Brahms would have appreciated Webern’s economy and symmetry, much the way Op. 118, No. 2 never quite repeats the same harmony. Napolitano shares an opulent Kinderstück where others might only treadle through the serial pinpricks. We’ve remarked on her Schoenberg and Bartók before.

Kaikhosru Shapurji SORABJI: Sequentia Cyclica (1948-49). Jonathan Powell (pno). Piano Classics PCL10206 (7 CDs) (http://www.piano-classics.com/). Through multiple stations of varying size and across eight-and-a-half hours, Sorabji dazzles with a convoluted succession of variations on the Dies Irae. Ostensibly there are 27 variations, however Variation 22, Passacaglia, itself includes 100 variants, and the conclusion, Variation 27, Fuga quintuplice a due, tre, quattro, cinque e sei voci ed a cinque soggetti, contains five substantial fugues whose last involves a 40-minute “stretto.” It delights to hear Sorabji cloaking the plainchant in different tonal centers and reimagined rhythms. Powell shall remain Sequentia Cyclica’s sole conqueror for quite some time.

[More Grant Chu Covell, Piano Factory]

[Previous Article:

String Theory 30. / EA Bucket 29: Violin, sometimes with electronics]

[Next Article:

Used Bin Troll Tweets PP.]

|