Piano Factory 9.

|

Grant Chu Covell [July 2012.]

“42 Vexations.” Erik SATIE: Vexations (1893). Stephane Ginsburgh (pno). Sub Rosa SR 294 (1 CD) (http://www.subrosa.net/). Shepherding the work’s first if not best-documented performance, Cage took Satie’s ludicrous directions seriously and stabled a team of pianists to crank out Vexations’ 840 required repetitions. It took them 18 hours and 40 minutes. Ginsburgh spends 1:09:30 to essay 42 repeats. It is possible to loop this Sub Rosa release, but that defeats the endurance requirement for performer and listener. Nonetheless, Ginsburgh’s tranche permits getting lost and stumbling into the work’s numbing tranquility. It’s a mere three lines, but Satie employs alternating flats and sharps, augmented intervals and parallel tritones across three irregular phrases intentionally difficult to memorize and sight-read. I suppose one could cheat with a clearer transcription. I doubt Ginsburgh cuts corners to provide this tranquil surface. The booklet contains Matthew Shlomowitz’s essay Cage’s Place in the Reception of Satie.

John CAGE: ASLSP (1985). Sabine Liebner (pno). NEOS 11042 (1 CD) (http://www.neos-music.com/). Distributed in the US by Qualiton (http://www.qualiton.com/). ASLSP abbreviates “as slow as possible” which Cage derived from a phrase in Joyce’s Finnegans Wake. The work contains eight two-line pieces. In concert, a pianist picks seven of the eight and repeats one. Liebner omits No. 6 and repeats No. 7. Not only is an entire performance impossible, but ASLSP thwarts virtuosic aspirations with unrelated chords and pitches. Unbelievably, Liebner’s 64:05 pass feels spry. I suppose it could be slower, but absent direction, ASLSP grinds tediously. Organ2/ASLSP (1987) demonstrates the most extreme leisureliness: An ongoing performance in Halberstadt, Germany expects to finish in 2640.

Federico MOMPOU: Música Callada (1959-67); Impresiones intimas: Secreto (1911-14). Jenny Lin (pno). Steinway & Sons 30004 (1 CD) (http://www.steinway.com/). Distributed in the US by Naxos (http://www.naxos.com/). I want to like Música Callada. Perched outside the mainstream, Mompou’s 28 pieces exude simplicity and prosaic airs akin to Satie and Cage. However, I find the tunes dreary. (I’d rather have been lulled by automated traffic lights.) Lin’s translucent portrayal looks for poetry, greatly contrasting Herbert Henck’s traversal (ECM 1523) which found uncharacteristic urgency.

Charles KOECHLIN: Les Heures Persanes (1916-19). Ralph van Raat (pno). Naxos 8.572473 (1 CD) (http://www.naxos.com/). In Koechlin’s day, Persian allusions conjured the Orient. Inspired by Pierre Loti’s travel diary, Vers Ispahan, Koechlin describes several days’ events in Impressionistic and bitonal styles. (Koechlin could explore dissonance and fairly remarkable harmonies often more prescient than Debussy or Schoenberg.) Those who know Koechlin’s orchestration will be astonished by the original’s bareness. Van Raat has an affinity for Koechlin. His reading is less drearily effete than Henck’s (Wergo 60 137-50).

Marc-André HAMELIN: 12 Études in all the minor keys (1986-2009); Little Nocturne (2007); selections from Con intimissimo sentimento (1986-2000); Theme and Variations (Cathy’s Variations) (2007). Marc-André Hamelin (pno). Hyperion CDA67789 (http://www.hyperion-records.co.uk/). Distributed in the US by Harmonia Mundi (http://www.harmoniamundi.com/). Hamelin’s 12 virtuosic etudes should satisfy the piano-obsessed. Étude No. 1 combines three Chopin etudes, and we’re to admire the battle. Others manipulate Chopin, Alkan and Liszt, and several spoof Rossini, Tchaikovsky and Scarlatti. Hamelin rarely plays it straight, littering his etudes with questionable notes, unresolved chords, and clusters. My favorite is No. 6, the Esercizio after Scarlatti whose constant missteps and bitonal distractions harry a perpetual-motion Domenico train, with a cadential I-vi-IV-V snapping the Baroque into the 1950s. Significantly less flamboyant, the other compositions don’t neatly sort into genres and periods. Everything seems to be based on a Rachmaninoff stock whether seasoned with Gershwin or Satie. Cathy’s Variations is a modest love letter to the composer’s fiancée tidily referencing Beethoven.

Robert SCHUMANN: Gesänge der Frühe, Op. 133 (1853); Sieben Klavierstücke in Fughettenform, Op. 126 (1853); Kreisleriana, Op. 16 (1838); Variationen Es-Dur über ein eigenes Thema, “Geistervariationen” WoO 24 (1854). Dina Ugorskaja (pno). Cavi-Music 8553217 (http://www.avi-music.de/). Distributed in the US by Allegro Music (http://www.allegro-music.com/). I offer my inevitable comment: Schumann was always mentally unstable even if the symptoms appeared late in life. Anyone tackling the late compositions must reconcile with an unbalanced composer and decide whether extra-musical concerns really matter. Ugorskaja, who presents several final solo piano works anchored around the familiar and earlier Kreisleriana, makes a convincing case for pervasive melancholy. I sought this release because of the Geistervariationen, the theme of which was purportedly dictated by angels, Schubert’s, or Mendelssohn’s ghost. Schumann incorporated the phantomic theme into several compositions before it appeared in his last publication. Brahms was sufficiently captivated to write his own piano four-hand variation set, Op. 23. Had Schumann persisted with the “an Diotima” reference in his original title for Op. 133, Nono’s string quartet might have proceeded differently, if not in name then perhaps in allusions. Ugorskaja’s restraint demonstrates how Schumann’s five Gesänge der Frühe fail to resolve convincingly. The seven quasi fugues in Op. 126 similarly leave listeners stranded with somber fugues that speed through major-mode strettos or potentially affirming resolutions. She patiently guides though Kreisleriana, siding towards precision where others leap towards blurring virtuosity.

Lodovico GIUSTINI: 6 Sonatas from Sonate da Cimbalo di piano e forte (1732). Wolfgang Brunner (fortepiano, Cristofori copy by Reiner Theimann, Nuremberg, 1995). cpo 777 207-2 (http://www.cpo.de/). Distributed in the US by Naxos (http://www.naxos.com/). Giustini’s Sonatas were perhaps the first published specifically for Bartolomeo Cristofori’s “stringed keyboard with hammer action,” the fortepiano precursor. Written to be presented as a private gift to the Portuguese court, and thus meant to disappear, Giustini nonetheless rose to the task and produced a dozen idiomatic pieces. Plucked stringed keyboard players are well aware that placing chords on unaccented beats can be difficult; however, hammer action permits such maneuvers and consequently different qualities of expressiveness Giustini explores. Brunner does admit that on non-Cristofori instruments these works might seem trifling. Indeed, the gentle accompaniment and single lines clarify the instrument’s crisp tone. Giustini writes in an “international style,” flexibly alternating dance movements with French and German characteristics thus enhancing their appeal with variety. Within the YouTube universe, you can find Brunner demonstrating perhaps the most exciting movement, the opening Balletto of Sonata No. 1 on the Cristofori copy.

Gerhard FROMMEL: Sonata No. 1, Op. 6 (1931); Sonata No. 2, Op. 10 (1935); Sonata No. 3, Op. 15, “Sisina” (1940-41, rev. 1962-80). Tatjana Blome (pno). Grand Piano GP606. Distributed in the US by Naxos (1 CD) (http://www.naxos.com/). Representing less-examined tendencies in 20th-century Germanic music, Frommel has been off the radar until now. These first three of seven sonatas proclaim competency with strong ideas fluently developed. Frommel also employs rhythm to delineate material masterfully. Concluding grand gestures reflect Liszt, even in the French-flavored No. 3, “quasi una fantasie.” No. 1 reveals Hindemith and Stravinsky connections — indeed Frommel thrives in a Schoenberg-free universe despite the similar grounding. No. 1’s finale tweaks Brahms among its Liszt-indebted figurations. The Second stands out perhaps because it so freely jousts with tonality. Its opening phrase concludes with a tail of unexpectedly whirling notes, like a skittering top. The notes imply we have an intentionally subversive piece, meant to tease the prevailing cultural requirements. When will Blome deliver the remaining four?

“Music of Tribute Vol. 6: Berg.” Giacinto SCELSI: Poema No. 4 (1936-39). Alban BERG: Sonata, Op. 1 (1908); Four Songs, Op. 2 (1909-10)*. Fanghiz ALI-ZADEH: Sonata for Piano No. 1 (1970). Ross Lee FINNEY: Variations on a Theme by Alban Berg (1952). Jacob GILBOA: Reflections on Three Chords of Alban Berg (1979). Hans Erich APOSTEL: Variations from Berg’s opera “Lulu” (1935)*. Ieva Jokubaviciute (pno), Marjorie Dix* (msop), Vladimir Valjarevic (pno). Labor Records LAB 7086 (1 CD) (http://www.laborrecords.com/). Distributed in the US by Naxos (http://www.naxos.com/). A piece-by-piece itinerary would still arrive at the same conclusion: A fascinating program of pieces and variations folds around Berg’s iconic Sonata, Op. 1 and the four songs, Op. 2, proudly proclaiming the Austrian’s influence. While it initially surprises to see Scelsi head the list, the early Poema No. 4 sounds nothing like the later “one-note” pieces. Ali-Zadeh may take Berg the furthest in her dynamic three-movement sonata. Finney, Gilboa and Apostel each offer variation sets the themes of which emerge crisp and clear: the Violin Concerto, Wozzeck and Lulu respectively. Finney and Apostel both studied with Berg. Several works receive their first recordings. Jokubaviciute sets a high mark.

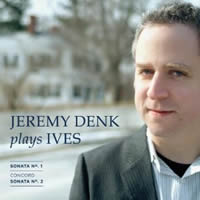

Charles IVES: Piano Sonata No. 1 (1902-10); Piano Sonata No. 2, “Concord, Mass., 1840-1860” (1915-19). Jeremy Denk (pno), Tara Helen O’Connor (fl). TDM 2567 (1 CD) (http://jeremydenk.net/). Especially in No. 1, Ives tends to oversaturate. While Denk has no trouble with that, this release could profit from an aerator. Denk easily navigates Hawthorne’s hairpin mood swings; however, the largest, densest passages lack razor-sharp crispness. The Alcotts similarly suffers. I wish the interfering Beethoven’s Fifth quotes were slightly more surgical. Perhaps it’s the piano or the recording. Compared to others, Denk’s Concord is one of the fastest (15:54, 10:53, 5:10, 10:15). For the obbligato instruments Denk adds flute but no viola.

Ali-Zadeh, Apostel, Berg, Cage, Finney, Frommel, Gilboa, Giustini, Hamelin, Ives, Koechlin, Mompou, Satie, Scelsi, Schumann

[More Grant Chu Covell, Piano Factory]

[More

Ali-Zadeh, Apostel, Berg, Cage, Finney, Frommel, Gilboa, Giustini, Hamelin, Ives, Koechlin, Mompou, Satie, Scelsi, Schumann]

[Previous Article:

String Theory 8 / EA Bucket 14: 29 Quartets, etc.]

[Next Article:

String Theory 9: 30 Quartets, etc.]

|