Plus de Musique de Chambre

|

Dan Albertson [November 2009.] [Here is the concluding portion, at least for now, of the chamber-music survey begun earlier this year. How could I thank Debbie Aubry enough, in the meantime, for her support, or Marcello Galati, for surpassing me in his knowledge of what is new and even, oy, what I have written? D.A.]

José MACEDA: Strata (1988)**; Sujeichon — Korean Court Music for Four Pianos (2002); Music for Two Pianos and Four Percussion Groups (2000)*. Chris Brown, Belle Bulwinkle, Charity Chan & Kanoko Nishi (pno), The Mills Performing Group*, Steed Cowart (cond.)*, UP Contemporary Music Players**, Ramón P. Santos (cond.)**. Tzadik TZ 8043 (http://www.tzadik.com/). Distributed in the US by Koch Distribution (http://www.kochdistribution.com/). This disc is not as full or as essential as its Tzadik predecessor, with the extraordinary mass Pagsamba among its contents, though it is a useful glance at later Maceda preoccupations. Strata is for five each of flute, guitar, cello and tam-tam, alongside ten percussionists on a choice of native instruments and is performed by a group from Maceda’s university, led by his disciple Santos. Here is a work of almost unending richness: Different performances will place greater emphases on strands within its 30 staves. Sujeichon is the embodiment of Korean court music and Maceda seems reverential, while ambulating around the tune itself. The assembled pianos give the music a solemn austerity. Music for Two Pianos and Four Percussion Groups is less severe and more uncertain of its intentions, with the groups never quite reconciled to mutual coexistence.

James DILLON: Dillug-Kefitsah (1976); Del Cuarto Elemento (1988)*; Traumwerk, Book 3 (2001-02)*; black/nebulae (1995)**; the soadie waste (2003)***. Irvine Arditti (vln)*, Noriko Kawai & Hiroaki Takenouchi** (pno), Arditti String Quartet***: Irvine Arditti, Ashot Sarkissjan (vlns), Ralf Ehlers (vla), Lucas Fels (vc). NMC Recordings D131 (http://www.nmcrec.co.uk/). Distributed in the US by Qualiton (http://www.qualiton.com/). James Dillon is a rare composer whose every piece is to be greeted with expectation. This collection spans almost three decades in his creative life, from the early and rather sprightly Dillug-Kefitsah to the bouncy, caustic strings and restless piano of the soadie waste. Like his earlier NMC disc, Dillon has chosen the crystalline acoustic of Suffolk’s Potton Hall for this recital and the pieces are as excellent as the sound. The piano duet black/nebulae, for instance, is a wonder, its fleet passagework rendered easily by Kawai and Takenouchi. Worthy, too, is the third book of Traumwerk, with the translucent third and obstinate seventh movements leaving indelible impressions. Dillon, in addition to his harmonic craft, is a master of the sudden ending, with no interest in summation.

Brian FERNEYHOUGH: Flurries (1997); Trittico per G.S. (1989); Incipits (1998); Coloratura(1966)*; In Nomine a 3 (2001); Allgebrah (1997). Christopher Redgate (ob), Bridget Carey (vla), Corrado Canonici (db), Ian Pace (pno)*, Julian Warburton (perc), Ensemble Exposé, Roger Redgate (cond.). Divine Art/Metier msv28504 (http://www.divine-art.com/). The music of Ferneyhough is more often discussed than heard, so this disc is a luxury, offering experienced listeners comparisons for each work. His scores encompass so many possibilities that new interpretations are almost the same as new pieces. Most striking is Trittico per G.S., played by Corrado Canonici in a tempo much faster than that of Stefano Scodanibbio for Montaigne Auvidis and with more direction as a bonus. Three works from 1997-98, Flurries, Incipits and Allgebrah, seem less assured than their competition on Stradivarius or Edition Zeitklang but the performances are compelling, despite the rather sterile acoustic. This sound is most damaging in Allgebrah, seriously dampening the range of the strings. The early Coloratura, alternating between plaint and exuberance, is noticeably slower than in the Edition Zeitklang recording. In Nomine a 3, a brief wind trio, is too direct to give rise to serious discrepancies. That these 2003 recordings have surfaced, after being delayed for some five years, is a boon to listeners with open ears. Will the string quartets, long the domain only of the Ardittis, be the next to be duplicated?

Camillo TOGNI: Three Studies on Morts sans sépulture, Op. 31 (1950)*; Flute Sonata, Op. 35 (1953); Violin Sonata, Op. 37 (1955); Piece for Guitar and Cello (1959); Five Pieces for Flute and Guitar (1975-76); String Trio (1978-80); Two Preludes for Piccolo (1980-81). Lorna Windsor (sop)*, Ex Novo Ensemble. Naxos 8.572074 (http://www.naxos.com/). Togni has long been neglected, yet I could never forget his Rondeaux per dieci for soprano and nonet from the 1960s. His negligence is, I am sure, a consequence of his lack of an outgoing personality to compete with Berio or Donatoni. The Venetian players of the Ex Novo Ensemble have a history with this music and the warm church acoustic in the Vicenza region is another asset. The music itself is either preliminary or expostulatory, with the early Sartre settings showing an ease of vocal writing that would later serve Togni well. A bright-voiced Windsor seems at ease. The flute and violin sonatas are accomplished and more lyrical than one may imagine from the era. Flautist Daniele Ruggieri and violinist Carlo Lazari both find assured accompaniment from Aldo Orvieto. Piero Bonaguri and Carlo Teodoro play the rare Piece that is, I gather, untitled; its name is given brackets. Its music is dark and supremely mysterious. The Five Pieces are not all duos, but are instead flute solos alternating with movements for both instruments. Their titles stem from ancient Greece, yet the music seems either atmospheric or pastoral. The String Trio, played by Lazari and Teodoro with violist Mario Paladin, is startling in its expression at times and seems even heftier when followed by the two minuscule Preludes that ensue. Comparisons are possible for the string trio and flute sonata on Stradivarius and for the preludes on Arts; no one could better Gazzelloni in the flute sonata, but Naxos’ modern recorded sound is a solid attribute. Togni deserves greater recognition. May the revival start here!

Morten OLSEN: Kata (2008); In a Silent Way (2007)*; Oryq (2007); Ictus (2005). Morten Olsen (elec gtr)*, Esbjerg Ensemble, Christopher Austin (cond.). Dacapo Records 8.226525 (http://www.dacapo-records.dk/). Distributed in the US by Naxos (http://www.naxos.com/). This composer was unknown to me until this disc and after hearing it, I have little interest in pursuing his work further. These four pieces are long-winded explorations indebted to the languorous music of Arvo Pärt, the driving banality of American minimalism and the prevailing “modernism lite” of Europe, in which certain features of modernism are used exploitatively and superficially in an attempt to distract one’s ear from the deficient music underneath. Kata and Ictus are for sinfonietta and manage very little coherence or any redeeming instrumental textures. The former, for instance, oscillates between the propulsive and the meditative, ultimately yielding only the mediocre. In a Silent Way is indeed titular theft from Miles Davis, but the piece almost redeems itself by not being a virtuoso vehicle for Olsen. Its understatement and its modest accompaniment surprised me pleasantly, but the music itself is forgettable. Oryq is cast in six movements and shares the instrumentation of Schubert’s Oktett, at least in principle; Olsen employs a bass clarinet as well as 24 tuned gongs, the latter never more than window-dressing. I had some hope after reading in the notes about the two short scherzi, supposedly meant to convey discomfort, menace or a raucous mood. I failed to detect these features, hearing only a few mild, dark rumblings. Saint-Saëns’ Danse macabre is more imposing!

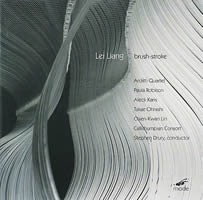

Lei LIANG: Serashi Fragments (2005)*; Some Empty Thoughts of a Person from Edo (2001)**; Memories of Xiaoxiang (2003)***; Trio (2002)+; In Praise of Shadows (2005)++; My Windows (1996-2007)+++; Brush-Stroke (2004)+ & #. Paula Robison (fl)++, Chien-Kwan Lin (alto sax)***, Aleck Karis (pf)+++, Takae Ohnishi (hpsi)**, Arditti String Quartet*: Irvine Arditti, Ashot Sarkissjan (vln), Ralf Ehlers (vla), Lucas Fels (vc), Callithumpian Consort+, Stephen Drury# (cond.). mode 210 (http://www.moderecords.com/). The music of Chinese composer Lei Liang (b. 1972), now based in the US, is immediately distinctive due to its lack of cliché. The current brand of musical “chinoiserie” written for public consumption is reductive, taking certain narrow traditions and relishing their dearth in the name of popular success. Liang, in contrast, is expansive. He begins with the music of his roots, far from cosmopolitan, and explores the netherworlds of these sounds. The resultant technique is called one-note-polyphony, but even that label seems inadequate. Liang is sure to be a fine discovery for the open-eared. The opening work, a mere seven minutes, seems typical of his current style. It is a stark reimagining of what the traditional Mongolian musician Serashi plays. Having heard Serashi himself on recordings brought forth by Liang on CRC, the discrepancy could not be more gaping. Based on improvisations, Some Empty Thoughts is much less taut and seems diploid, with meditative sections framed by a central manic cadenza. Memories are literal, with the composer’s inspiration coming from the Yao people of Hunan. The saxophone seems onomatopoeic at times, crying or screaming, but never excessively; a dramatic pause in the middle is a fine device. Trio for cello, piano and percussion is a duo with the pianist’s contributions seeming irrelevant and the music never reconciling its Apollonic or Dionysian impulses. In Praise, its title lifted from the more “polite” world of the oft-salacious Jun’ichirō Tanizaki, makes rich use of the lower flute registers, while the four miniatures of My Windows display less personality. For 15 players, Brush-Stroke has a lucid orchestration that is marred occasionally by intentional vocal interjections. Overall, much is to be praised here: the sumptuous without the ostentatious.

[More Dan Albertson]

[Previous Article:

From a Pianist’s Working Diary]

[Next Article:

Haydn Year Highlights 1.]

|