Rebecca Saunders on Kairos

|

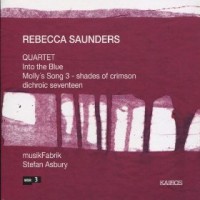

Robert Kirzinger [June 2002.] Rebecca SAUNDERS: QUARTET; Into the Blue; Molly’s Song 3 – – shades of crimson; dichroic seventeen. MusikFabrik, Stefan Asbury (cond.). Kairos 0012182KAI (52:29). I think I have about half of Kairos’ catalog of some 35 titles at this point, the label being as close to a sure thing as I’ve come across. I’d probably own all of them if they were easier to get. Although I know how to go about getting what I haven’t found easily, the annoyance of the process combined with a pretense toward thriftiness has kept me from obtaining the other half. It’s only a matter of time or better distribution. What do I mean by “sure thing”? More than half of the Kairos discs I own I purchased either without knowing the music at all or with little or no previous knowledge of the composer. I’m so impressed with the composers and performers I’m already familiar with on Kairos’ roster that I had no real hesitation in speculating on Matthias Pintscher’s, Rebecca Saunders’, and Hanspeter Kyburz’s releases. Nor have I been disappointed. (Pintscher has since signed with Teldec exclusively, but apart from his first disc on that label there’s little available from any of these composers.) News from Europe! I’m listening to Rebecca Saunders’ disc right now. Saunders is a 35-year-old London-born composer working, I gather, primarily out of Berlin. A violinist by training, she attended Edinburgh University and studied with Wolfgang Rihm at Karlsruhe (1991-94) and with Nigel Osborne back at Edinburgh, where she earned her doctorate. (Rihm’s influence is apparent; I’ve never heard Osborne’s music.) She was a composer-in-residence at Darmstadt in 2000. Her music is frequently performed on the continent. Apparently her home country has not yet seen fit to push her forward as has been done with your Adèses and your Andersons and so forth, or maybe there’s just a geography thing happening. Or maybe she’s adored in Britain, and I just don’t know it. The Kairos disc of Saunders’ music comprises four pieces: QUARTET for accordion, clarinet, double bass, and piano (1998); Into the Blue for clarinet, bassoon, piano, percussion, cello, and double bass; Molly’s Song 3 – – shades of crimson (1995-96) for alto flute, viola, guitar (with bottleneck slide), four radios, and music box; and dichroic seventeen (1998) for accordion, electric guitar, piano, two percussion, and two double basses. Annotator Robert Adlington says something I think is right on the ball about Saunders’ music but that applies to Rihm’s as well, and goes back, I think, to Varèse. “That Saunders’ music represents a continuation of the time-honoured strategies of earlier generations of avant-garde composers is underlined by two recurrent textural gestures. The first…comprises a succession of concise sonic ‘objects’ interspersed by carefully measured periods of silence. [Silence] is the ‘substance’ that endows the sound-objects with their imaginary materiality — their impression of physical boundedness.” The “objects” of which Adlington writes are complex, self-contained gestures, analogous in a way to such “classical” gestures as the opening measures of Tristan und Isolde, or the first chords of the Hammerklavier Sonata — moments that contain within themselves the embodiment of an entire musical world, which in the case of Wagner or Beethoven is then explored via explosion and deconstruction (if you’ll allow the term). Whereas we’re often taught to identify this kind of music by its (melodic) themes, such an approach ignores what the great composers know; that is, the significance of such gestures is not found in one parameter (i.e., the tune), but in the totality of its musical potential: harmonic, rhythmic, timbral, melodic, etc. (This is why Bach could write so transcendently starting with a theme as banal as a major scale or arpeggiated triad.) Saunders, like Rihm, seems to approach these complex sonic units as component parts of yet more complex larger spans: We might say that the timbres, rhythms, and other parameters of a given sonic unit fuse utterly into the identity of the figure, which in turn is used as an indestructible whole. Any variation of the whole might be analogous to the variations we perceive in a sculpture (or a tree) as we walk around it, viewing from different angles. The object itself remains the object. Such an approach is similar to Feldman’s, perhaps, but Saunders finds beauty in a very different sound world, one that goes beyond even Rihm’s, less focused on pitch relations and more on subtleties of timbre we can’t always immediately apprehend. In this her music shares some kinship with Lachenmann’s or Hosokawa’s, and with that of other composers whose use of “acoustic” instruments has been influenced strongly by electronic music / recording technology (thinking of Ligeti’s Cello Concerto and his Ten Pieces for Wind Quintet). I mentioned that Saunders’ music isn’t really about pitch, or about changing pitch in such a way as to evoke melody or harmony. Within a passage, she tends to limit pitch to a narrow range in order to keep changes in dynamics, timbre, articulation, and other parameters from becoming secondary to the moment. (Adlington talks about this as well.) To return to my sculpture metaphor, it’s as though one is studying a particular detail, the join of two sections of a David Smith work: One’s eye picks up the subtleties of angle involved, the beginnings of surface rust, the slight spatter of a weld, not feeling the need necessarily to continue to follow the shape of the rest of the piece (we can take that in at our leisure, too), just being made aware of the moment. Obviously differences in medium allow Saunders better to control the time one spends decoding or simply enjoying a moment, and this can be a drawback as well, if we don’t get it; but I don’t think it’s as crucial in this music to be able wholly to relate what we’re hearing at a specific moment to the complete piece. QUARTET begins with a sharply attacked chord, a slap noisily resonant with the strings of the piano: It’s in fact the result of the piano lid being slammed shut. The double bass provides the attack’s decay. The ensemble develops a morphology of the gesture, modifying it as though testing its use in other contexts and with varying meanings. This approach obtains also in Into the Blue, which, like QUARTET, falls into a large form roughly tripartite. Modified bowing and blowing techniques and piano-as-zither are joined by police whistle and other noisy sounds in percussion; once again the traditional piano music (keys pressed and hammers set in motion) near the end of the piece comes as a bit of a surprise. Molly’s Song 3 – – shades of crimson, one of several Saunders works referencing Joyce’s Molly Bloom, brings in further additions to the sound-potential of its ensemble with four radios, slide guitar, and music box adding to extended techniques in the acoustic instruments. When the untuned radios appear by themselves towards the end of the piece, it’s as though they’re an extension of the sound world already created. Their abrupt cessation, leaving a moment of silence, is amazing. The “sonic objects” are less well defined, which implies not that this approach is absent but that there’s something else going on that takes precedent — if I’m hearing aright, something related to linearity and counterpoint, with the instruments having an independence and self-sufficiency not found in the first two pieces. In dichroic seventeen, accordion and distorted electric guitar provide the extensions of an already widened palette, vying with harmonics and percussive effects in the piano and varied metal objet-trouvé percussion. Very cool indeed. As in QUARTET, piano music of almost traditional nature emerges from the texture, surreally. Style becomes a kind of object, one with “meaning” attached, but that’s undermined by new context. One of the obvious conclusions I drew from listening to this music is Saunders’ delight in the palpable nature of sound and in the physicality of its creation. Listening to moments in each of these works, I’m reminded of hours spent endlessly fascinated by experimenting with the nontraditional timbres of guitars, basses, electric drills, broken pianos, found objects, and conventional instruments of all kinds. Saunders is apparently meticulous about her notation of such techniques as quick, loud release of the piano’s pedals, different bow pressures, using fingernails on strings, and the like. A beautiful dichotomy between harsh sounds and delicate deviations mirrors others, between pitch and noise, line and block, sound itself and silence, but there are no hard and fast boundaries between any of these extremes. As Adlington writes, “Here is a music that treats sound as an end in itself rather than as a vehicle for communicative statements: it is a music about itself.” Whatever the meaning of this music is, it’s here.

[More Robert Kirzinger]

[More

Saunders]

[Previous Article:

Modern Nasty Recordings]

[Next Article:

WHRB’s Spring 2002 Orgy Period]

|