Schumann’s Kreisleriana, Op. 16

|

Beth Levin [May 2014.]

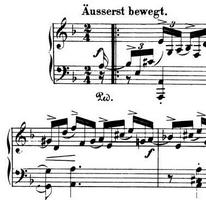

Composed in 1838 and dedicated to his friend F. Chopin, Kreisleriana is a pianistic standout, worth perhaps two Carnavals. 1. Äußerst bewegt (Extremely animated), D minor The treble climbs in slurred, accented intervals to a brilliant high D at measure 8. That D feels triumphant because of the treacherous intervals before it, smaller ledges leading to the mountaintop. Pedal marked in the bass helps the dotted (staccato) octaves carry weight and tone as they support the mercurial right hand. Measure 9, ff: an intensity is reached here and held by szforzandi that grow from tiny crescendo – A-Bb-A, A-Bb-A – that minor second tugging, yearning. The treble surrounds the sparser bass line with 16th notes in chordal patterns – simple, elegant, filling out the harmony, a Puckish midsummer dance. At measure 25 a switch to the key of B-flat major removes the music from its unrequited state to a place of temporary peace, utter repose, almost resolution. The two-note slurs and falling 16ths, a gentle rain. The opening is reiterated at measure 49. We must leave the sweet garden to relive darker times. Throughout the work this pull of conflicting moods, dynamics, colors and emotions will continue to thrill. Note to pianists: Don’t be afraid to use rotation in the opening intervals and to play at different parts of the key – it’s wild! 2. Sehr innig und nicht zu rasch (very inwardly and not too quickly), B-flat major A sublimely serene melody rises and falls twice before stretching out to fulfill eight measures. Schumann seems always to be using Nature as his guide. And Bach. The middle voices at measure 5 echo the opening theme and work well to counterbalance the line above them. At measure 7 the bass enters with important material and the performer searches for just the right sound – think Chaliapin – to differentiate the lines. Looking, say, at measure 24, there exists a glorious duet between soprano and alto. The pianist must be alert to this internal action to give it character. Intermezzo I Sehr lebhaft (very lively) This movement breaks the serenity with its pointed left hand working against two-note slurs in the right, all accents, dots and speed. Not merely new material but a second, outgoing character is introduced. Schumann is nothing if not about contrast. Erstes Tempo at measure 55 returns us to the utter calm of the opening. The continual repetition of this legato melody beckons to a place of introspection. Intermezzo II Etwas bewegter Yet another variation within a variation with its swirling legato lines and rich woven textures. Schumann presents a singing melody at measure 92 and answers it further on in the bass and alto, the effect being one of intricacy, color and variation. He highlights a melody by imbedding it inside patterns of running 16th notes and leaves no spaces, a river of sound. The music at measure 119 has an improvised feel and forms a perfect transition – using fragments of the theme and the Intermezzi to seamlessly work back to the first material at the first tempo. We are home. 3. Sehr aufgeregt (Very agitated), G minor Accented triplets act out a sprite-like melody in G minor to form this movement’s character. An excitable piece following a spiritual one keeps us on guard. What next? I think Schumann was aware of qualities that seduce the ear. While his music is never programmatic it has a visual aspect. His musical characters spring to life in the hands of a good interpreter. At measure 33 the music shifts to B-flat major (still sharing E-flat and B-flat from its relative minor). Again Schumann creates a refuge in the midst of turmoil. A small suspended high G at measure 41 is delicate and touching. He recreates moments of music as feeling, of the felt, the known. Measures 61 to 67: An arcing line over repeated B-flats creates a feeling of restlessness in the listener even as it makes a transition to the theme. He bends the music like clay. At measure 85 the sprites return to play. A bombastic coda at 116 brings out their wild side. The falling octaves at 140 are powerful, requiring a sense of abandon to the very last note. 4. Sehr langsam (Very slowly), B-flat major/D minor Ah, permission to play slowly – to breathe, sing, dream. Schumann’s turns, grace notes and rolled chords, usually performed quickly here take on an aspect of slow motion and are given more of a melodic role. A ritardando in this tempo stretches rhythm to the breaking point as in measure 5 and again at measure 10. One’s sense of timing expands, the extreme becomes the norm. Don’t be afraid. Pedal markings here and there aid in the suspension of time and the blending of colors. Leonard Shure once told me to play with clarity despite the pedal. It can be used quite artfully in Movement 4. As in most of Kreisleriana a middle section emerges with contrasting ideas to the original theme. Here at measure 12 the music is suddenly flowing after being held in limbo. A tender and singing melody in quarter notes debuts as sixteenths provide motion and harmony around it. One cannot describe adequately the beauty of Schumann’s melodies, their fragility, the tenderness they relay. As with his songs, one experiences true soulfulness. Chopin knew how to sing at the piano; in this section Schumann shows his love and respect for Chopin. Measure 24 returns to the original material and tempo ending with an Adagio measure that serves as a perfect segue to movement 5. 5. Sehr lebhaft (Very lively), G minor Some of movement 3’s impishness returns with an infusion of dotted rhythms, one of Schumann’s trademarks. Long…short long…short long…etc. Here they add punch and contrast to the legato eighth notes without elongating dots. A musical gesture begins to build in measure 15, Schumann seeming to reach higher and higher, and by the third time peaks on a high F. So many of his melodies seem to reach upward, perhaps never to be satisfied. He knew how to create leaps and large shapes and transform them to physical entities. At measure 51 he opens up to a delicious section of harmonies and eighth notes in unison that verge on the ultra-Romantic. One has to keep from getting lost in the soup. At measure 67 he goes all out in ff and the momentum and power are overwhelming. Again, when confronted with such force of beauty, the performer must be in control or fall over the edge. One works for a sense of abandon and control that can seem to coexist. 6. Sehr langsam (Very slowly), B-flat major The opening, in lulling 12/8, is short-lived. At measure 5 a sharp key change to C minor in forte ignites several bars of a fiercer mood. Surges of quick notes like small glissandi climb to and fall from accented chords. After a fermata at measure 8 a pp transforms the driving notes to a delicate filigree like the dissipation of anger. At measure 11 the opening theme appears in the bass, taking on a more lumbering quality. Soprano lines take over and gradually return us to the original material. While Schumann’s brush strokes are simple, the result is orchestral. The opening few bars seem to provide Schumann with the means to create an always changing canvas, a now-you-see-it-now-you-don’t sleight-of-hand. Schumann the magician! 7. Sehr rasch (Very fast), C minor/E-flat major Movement 7 is short and wild, a great release from the more deliberate 6. In a suite of dances such as Kreisleriana the performer must time the entrances just so, sometimes letting several beats elapse before moving ahead. Schumann writes a fermata or hold at the end of his movements; the exact timing is up to the performer. Accented bass chords support the rushing treble sixteenths in forte with a fragment of a fugue appearing at measure 36, all unrelenting, never coming up for air. Here as in the others a second contrasting section emerges, in this case a hymn-like arrangement of chords in quarters that slows down the harmonic rhythm and frenetic energy. A ritardando, another, one more signal, the end. Schumann’s use of ritardando and other markings reflect his temperament. He would often place three ritardandi within the space of a few measures and thus maneuver time in a manner close to Nature. 8. Schnell und spielend (Fast and playful), G minor Schumann wrote: the title is understandable only to Germans. Kreisler is a figure created by E.T.A. Hoffmann … an eccentric, wild and clever Kapellmeister. To paraphrase Koji Atwood, Kreisler, kept alive by music, personifies the Romantic soul in its struggle to invoke the deepest of personal feelings, often at the risk of madness or death. Hoffmann had intended that his hero would go mad or pass his final days in a monastery. Ultimately, Schumann emulated Kapellmeister Johannes Kreisler all too well: Unable to control the demon of Art, it destroyed him. We have arrived at the final piece, an amalgam of themes and characters rich in paradox and in longing. Contrast in Schumann is never merely black/white or dark/light but rather a juxtaposition of worlds felt at the deepest level. An elf opens the proceedings: G minor, pp, staccato. Only a slur at measure 2 adds poignancy to the otherwise carefree character. A bass figure enters at measure 25 with a comedic feel: rolled chords as melody, heaviness on the heels of Puck. Arrival at measure 73 (Mit alle Kraft – with all one’s strength) is a critical moment for the work as a whole: a heartfelt melody in forte that seems to embody Schumann’s yearning (perhaps for Clara) and for the pursuit of Art he felt to be just beyond his grasp. The performer must dig deep to portray a depth of culminating passion at the heart of Kreisleriana. At measure 113 the tiny elfin feet that began the movement return (in ppp and a decrescendo) to the final notes of Kreisleriana.

[ArkivMusic shows 142 current entries but picking some isn’t impossible. On top I’d put Cortot (1935) and Horowitz (1969 Sony). Richter, a great Schumann player, never recorded it. Kempff may seem too mild for the work’s extremes, but on his scale the 1956 mono has much to offer. I like a few that break into pairs: duo partners Lupu (1993) and Perahia (1996-7), and Argerich (1984) and Rabinovitch (1996); or Connoisseur Society mates Pamela Ross (1991) and Cynthia Raim (2005). Kreisleriana is placed in the context of Schumann’s last efforts by Schiff (1997) and Ugorskaja (2010). Beth is playing it Aug. 17th at Spectrum in NYC and Sept. 27th in Munich. I’ve said her Davidsbündlertänze would enrich the catalog. W. M.]

[More Beth Levin]

[More

Schumann]

[Previous Article:

Piano Factory 13.]

[Next Article:

Used Bin Troll Tweets H.]

|