Mostly Symphonies 35. / (Dis)Arrangements 11: The Finale of Bruckner’s Ninth

|

Grant Chu Covell [September 2019.]

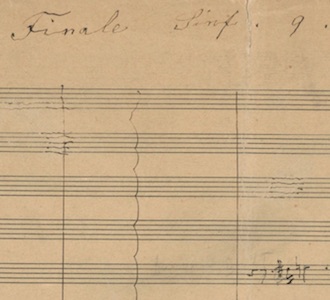

Everybody’s favorite archaic Romantic, the Austrian composer Anton Bruckner died having completed an orchestral draft of all four movements of his Ninth (1887-1896). He worked at the symphony on the morning of his last day (October 11, 1896). The score was at his bedside when he died, and treasure seekers pilfered pages of the Finale. When it came time to stage a performance in 1903, conductor Ferdinand Löwe simplified the music, believing the various dissonances (such as the unresolved dominant 13th chord in the Adagio) to have been the folly of a demented mind (the Finale offers a striking minor-ninth fanfare also easily bowdlerized). The vandalized Finale was set aside, and the rumor began that Bruckner never completed the work. Löwe’s version remained the standard until 1932 when Alfred Orel took a restorative look at the manuscripts.

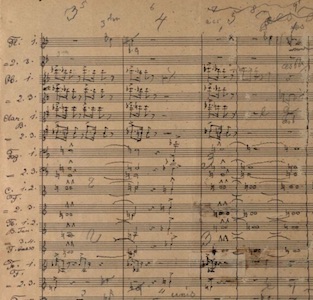

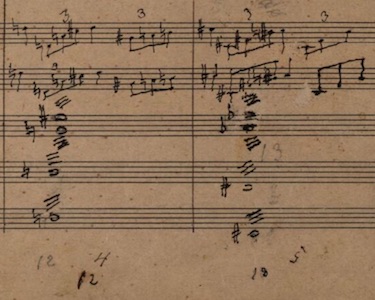

At his maturity, Bruckner designed his music by building sections from precisely sized phrases. Perhaps it was some form of obsessive–compulsive disorder. It is an open secret that you can repeatedly count 1-2-3-4-5-6-7-8 throughout his edifices. His drafts show such tallying, and because measures and pages are numbered, we can infer how many measures might be missing. The composer planned his proportions and would use shorthand and symbols to indicate recurring ideas and modulations. There are plenty of sketches and autograph pages, and it has been possible to construct a satisfactory performing edition. Since Löwe’s first, abridged performance of the three “complete” movements, a false aura has descended. Bruckner had a share of admirers but more detractors. It did not help that the religious composer dedicated No. 9 “to the beloved God” (“dem lieben Gott”), which insinuates inapproachable aims. It also did not help that the insecure composer, continually prodded into significant revisions of already completed works, suggested that the Ninth could be rounded out with his 1883 Te Deum. Such a conclusion would be absurd: The Te Deum warrants vocal soloists plus chorus and inhabits a different key (C major instead of the Symphony’s D minor). The Coda is the problem. There are drafts, however it is likely that near-final versions of these pages in orchestral form were the ones stolen from Bruckner’s rooms. Supposedly, he had wanted to incorporate themes from the Fifth, Seventh and Eighth into the Finale. This is an interesting proposal, probably difficult to bring off effectively. To my ear, it is awkward when the Feierlich’s first theme returns. There’s also a sawing figuration reminiscent of the Sixth’s Finale. I imagine messy counterpoint played fff in order to consummate the multi-symphony deed. Nonetheless, a principal motive from the Te Deum does arrive, handled elegantly and substantively, suggesting that Bruckner might well have been able to pull off a “greatest hits” coda.

Across the past decades, performing versions of the Ninth’s Finale have become more prevalent. The preeminent contender has evolved across several decades with a core but varying team of musicologists and musicians. There are also fanciful completions which distract tremendously from appraising Bruckner’s ultimate statement. * * * Obsessives should acquaint themselves with the articles and discography at abruckner.com, the home of The Bruckner Archive, The Bruckner Society of America, and an extensive Bruckner discography. You may want to consider the Bruckner Bobblehead. The autograph manuscripts can be inspected, and the score of at least one edition, the Conclusive Revised Edition from 2012, can be purchased.

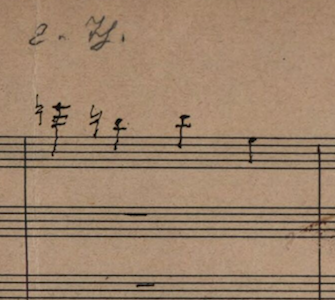

There are recordings of just the pages Bruckner completed (cleaned up and lightly edited). Among these is Nikolaus Harnoncourt’s demonstration lecture (in German and English) alongside a powerful recording of the first three movements (Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra, RCA BMG SACD 54332). Understandably, John A. Phillips’ edition of the fragments has no filler, thus Harnoncourt’s excerpts halt abruptly. The gaps are covered with a gallant lecture, wherein the conductor implores us to search our homes for the missing pages. Yeah, sure, they’re right here wedged between a folio with something in B minor by Schubert, and a bound volume labeled in Finnish with “Symphonie.” Harnoncourt gushes over Bruckner’s genius. He describes wonderful moments that are hard to discern, such as an ascending horn phrase suggesting the great hereafter. The conductor offers nothing from the coda. The minor-ninth fanfare is illustrated twice. Once as written and again when coerced into bland octaves. Bruckner’s dissonance makes sense in context, easily becoming normal. Listen to Harnoncourt just for this demonstration. The standard three movements appear after the Finale lecture, a coy move: Harnoncourt has it both ways, divulging the new, but maintaining the status quo. To his credit, the Vienna brass project mightily and the strings are forthright. Had he tackled a completed Finale, his performance might be the most vigorous. Peter Hirsch presents the extant sections in discrete tracks (Sony CD SK 87316, RSO Berlin). There are days when this broken presentation with its unexpected pauses is preferable. The Finale is paired with Georg Friedrich Haas’ idiosyncratic 1999-2000/2001 orchestration of Schubert’s incomplete C-major piano sonata, D. 840, which inexplicably escaped mention back here.

Bruckner’s diary indicates he began the Finale on May 24, 1895. After completing a symphony’s conclusive draft, it was his habit to make one last pass across all the movements and adjust dynamics, phrasing and articulation. Bruckner called this final process Nuancieren. This never happened for the Ninth. Thus we should entertain that the composer may have altered the other three parts, perhaps only on the order of dynamics and instrumentation. But we will never know. The Scherzo we have today, whose martial hammering anticipates Holst’s Mars, offers the third incarnation of the Trio. The Finale’s foremost performing edition is the varied combination of four people’s research: Nicola Samale, John A. Phillips, Benjamin-Gunnar Cohrs and Giuseppe Mazzuca (generally abbreviated as SPCM). The work began in 1983 when Samale and Mazzuca created a realization which has since progressed through many improvements, including incorporating Phillips’ definitive analysis of the sketches (2002) as well as reflecting learnings from the many interim performances. The most current revision is the 2012 Conclusive Revised Edition (CRE). Listening to recordings as the SPCM team’s effort evolved reveals sensible simplifications. Bruckner’s drafts contain plenty; it makes little sense to create extra. Bridging measures become simpler, and there are fewer melodic, harmonic and rhythmic inventions. The CRE is dedicated to Simon Rattle. His 2012 release (Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra, EMI CD 9 52969 2) is resolutely mainstream. Start and end here for a competent Finale. Perhaps orchestra and conductor remain unconvinced. Earlier recordings of prior SPCM editions commence similarly because the Coda warrants the most finessing. Eliahu Inbal (Radio-Sinfonie-Orchester Frankfurt, Teldec 2564680228) powers through the first reconstruction, Samale and Mazzuca’s 1984 draft, with strong violins and warm brass shapes. With Johannes Wildner (SPCM 1996, New Philharmonic Orchestra of Westphalia, Naxos 8.555933-34) and Marcus Bosch (SPCM 2005, Aachen Symphony Orchestra, Coviello Classics SACD 30711), the once grandiose restatement of the first movement’s principal idea shrinks. Bosch also dilutes the dissonant ninths perhaps by reassigning the lower note to trombones. Friedemann Layer’s orchestra (National Theater Orchestra of Mannheim, Lirica CD-0105) is thin, perhaps not what one wants for Bruckner, although he makes sense of the tempos (SPCM 2007).

The Conclusive Revised Edition ought to find its place. I suspect there remains further balancing to do. I expect more pregnant silences (SPCM does gradually grow more comfortable with simplicity and rests), however the torrential string filigree in triplet rhythms is commonly hard to appreciate.

Others have stepped into the completion business. Gerd Schaller has attempted several different stabs at the Finale, starting with a release of William Carragan’s 2010 version (Philharmonie Festiva, Profil CD PH11028), and then offering two completions of his own in 2015 (Philharmonie Festiva, Profil CD PH16089) and finally in 2018 (Philharmonie Festiva, Profil CD PH18030). Considering his most recent attempt, Schaller visits edits upon what Bruckner had finished, including unexpected staccato articulation for the flute’s initial statement of the Te Deum motive which appears legato most everywhere else. Schaller’s overall conception is nonetheless satisfying. Outside of SPCM, he has a fine grasp of Bruckner’s style and designs a consistent structure. His detailed booklet notes insist that the key to Bruckner’s intentions can be discovered in the harmonic progressions and the whole-tone scales and tritones. Less intentionally thought-through completions add melodies and dramatize notes that run counter to the repeating sequences and chord progressions. On a previous day, I preferred Carragan’s completion over the SPCM 1996 collaboration as performed by Wildner. Carragan did get his realization out of the gate ahead of SPCM. Now I hear material that runs counter to Bruckner’s late style. Admittedly the Ninth’s movements differ from one other in terms of severity (Scherzo) or chromaticism (Adagio), however internally they are consistent. In Talmi’s performance (Oslo Philharmonic Orchestra, Chandos CD 7051), Carragan’s 1979-83 fillings tend towards Wagner and Verdi, and there are secondary voices that cut against Bruckner’s repetitive mannerisms. Now that I know what Bruckner left, it’s apparent that Carragan contributed too much. The Coda is the hardest section to complete acceptably. Incorporating sketches and material that Bruckner had once considered, Schaller’s hefty triumph nevertheless grinds. Nors S. Josephson (John Gibbons, Aarhus Symphony, Danacord CD DAOCD 754) imagines Bruckner would have repeated and sequenced his existing ideas. Josephson avoids dissonance, and his patterning grows dreary. The last bars of Josephson’s Coda glow too exultantly, as if Mahlerian (Bruckner achieves his summits through hard work, Mahler often gets lucky with a change of weather). Nicolas Couton explored Sébastien Letocart’s 2008 completion with the MAV Symphony Orchestra (Lirica CD-107). At around 17:05 unfortunate wind balances suggest an ondes Martenot. Upon the ultimate D-major arrival, the added sixth resolving to the fifth acts as an appoggiatura stylistically alien in late Bruckner. Rattle is just fine for the simply curious or those who approach their listening as an itemized list. Schaller has wonderful sound and makes interesting, inoffensive choices. Bosch merits stocking if you’re into duplicates, and Gibbons (Josephson) and Couton (Letocart) add to the conversation if alternates appeal.

We can get used to anything under the right circumstances, especially when consensus insists. We’re used to the strange four-note chord that opens the Scherzo (E-G#-Bb-C#), so perhaps we’d accept any Coda if we were told it was Bruckner’s. Here are two fanciful efforts. Gottfried von Einem explored Finale snippets in his 1971 Bruckner Dialog, Op. 39 (Wiener Symphoniker, Lovro von Matačić, Orfeo C 235 901A), a modernist rummage which occasionally reveals his fellow Austrian’s motifs. This is not a completion of the Ninth. There is no development, no desire to bring a conclusive shape to the material. It reads like a casual stroll around discarded transitions, and a listener could completely overlook the Bruckner. At the 1974 premiere, I’m sure that few listeners would have recognized the Bruckner bits although they sound less like the surrounding Richard Strauss castoffs. Imagine a discount clothing store in a cathedral. I can believe that von Einem had access to a handful of pages and spliced them into something else he was working on. At the ludicrous extreme is Peter Jan Marthé’s astonishing free-form rhapsody, Bruckner Symphony IX Reloaded (European Philharmonic Orchestra, Preiser Records PR 90728). Marthé’s recording delivers the first three movements at deflated tempos, unreasonably sedated. Sluggishness does not result in grandeur. The Finale lunges between moody caricatures of the original and second-rate Pettersson or Shostakovich-like anguish. Although, frankly, Marthé channels the bombast of Helgoland and Psalm 150. I imagine that Marthé leveraged the sketches as a scaffold for timing but not content since contours of the torso guide Marthé’s macabre ramble. Marthé offers a lively essay explaining his motivations. Bruckner’s pages include powerful content. Why not use them? At the right time, this fantasy can amuse, although it’s often outrageous. Thanks to the persnickety folks keeping discogs.com precise, we can enjoy the Süddeutsche Zeitung’s quote on the back of the release: “… music that bursts every known boundary of Bruckner’s thought.” I fear but expect an enterprising naïf will employ Artificial Intelligence to solve this puzzle. Which in turn will capture the fancy of a promising middle-tier orchestra. However, the results will sound dreadful. Alternately, perhaps perversely, someone should follow Berio’s example in Rendering and announce the hypothetical passages with aural clues such as tinkling celeste. * * * Recent releases of the three-panel Ninth include Andris Nelsons with the Gewandhausorchester Leipzig, part of an ongoing cycle (DG 0289 483 6659 0). DG and Nelsons are padding the releases with Wagner. The Sixth and unfinished Ninth are preceded with Siegfried Idyll and the Act I: Prelude from Parsifal respectively. Perhaps the Adagio could have been followed with a slab from Götterdämmerung, but why not the Finale? I grew up on the three-movement version. Conductors and orchestras have figured out how to make the Feierlich, Scherzo and Adagio compelling. Done right, the Adagio’s tranquil close can bring down the house. After all, it is an offering to God, and was presumed to be Bruckner’s last utterance. I have soaked myself in motley recordings of the Finale attempting to erode my three-movement bias and build new memories. The Scherzo’s hammering aggressiveness and the Adagio’s bold minor-ninth leaps should prepare for the Finale’s astonishing whole-tone harmonies and tritone-chord progressions. Many passages deserve to be heard, perhaps some of Bruckner’s most inventive cascading string arpeggios and luminous brass chorales. It has been equally disconcerting and rewarding to become familiar with something so alluring and imperfect.

Bruckner Symphony No. 9: Finale

[Previous Article:

Collecting Is Forgetting]

[Next Article:

Used Bin Troll Tweets MM.]

|