The Unexpected

|

Grant Chu Covell [April 2018.]

Graciela PARASKEVAIDIS: algún sonido de la vida (1993)1. THE PRINCE MYSHKINS: Var. songs2. Galina USTVOLSKAYA: Duet for violin and piano (1964)3; Symphony No. 2, “True and Eternal Bliss!” (1979)4. Ben JOHNSTON: String Quartet No. 5, “Lonesome Valley” (1979)5. Elizabeth England1, Ben Fox1 (ob), Rick Burkhardt2 (accordion, voice), Andy Gricevich2 (guitar, voice), Gabriela Diaz3 (vln), Stephen Drury3,4 (pno), Kepler Quartet5: Sharan Leventhal, Eric Segnitz (vln), Brek Renzelman (vla), Karl Lavine (vlc), Ryne Cherry4 (voice), Sound Icon4, Jeffrey Means4 (cond.). Fromm Foundation at Harvard University presents Fromm Players at Harvard, John Knowles Paine Concert Hall, Cambridge. March 31, 2018, 7pm. This was a disconcerting evening. Kudos to Chaya Czernowin who gathered such variety under the “Resistance and Hope” slogan. Yes, we’re all into resistance and speaking our minds these days, and some of these composers and acts held to the directive better than others. A duo for two oboes by Graciela Paraskevaidis (1940-2017) started things off. The first movement of algún sonido de la vida hung on a high C-sharp which was aggressively flung back and forth between the two winds, oft tinged with startling multiphonics. The subsequent two movements utilized more notes, but maintained the hermetic motion. The last movement confined the reeds to three pitches (C, B and B-flat). Paraskevaidis studied with Xenakis and others, eventually settling in Uruguay. There were no melodies to hang on to. The oboes’ squawk could be abrasive; the two players were fused together as if one. In an ideal performance, which happened here, we start to hear frequencies and tones not actually played, but created through the close beating and vibrations. The title is borrowed from a poem by the Argentinian Juan Gelman meaning “any sound out of life.” We should be hearing more of Paraskevaidis’ music. The final pair of the concert’s first part appeared to be the more traditional violin and piano combination. However, Galina Ustvolskaya’s Duo is a large, forbidding occurrence. Delineated by pungent silence, single notes and clusters are dispatched precisely in square rhythms. The pacing, slow repetition and frankly unmusical gestures prove powerful and startling. Both violin and piano may quickly alternate registral extremes. Now and again a simple melody would appear in straightforward quarter notes, or the accompaniment would be small clusters derived from minor scales. This requires a different type of virtuosity other than, say, a nostalgic Kreisler miniature for the same players. This concert was inked into my calendar because the Kepler Quartet was set to play Johnston’s Fifth. It was fabulous. Derived from the hymn Lonesome Valley, this quartet may not have the structural or canonic rigidity of other Johnston quartets, but it certainly offers extended passages of eerie bittersweet harmony which only just intonation can provide. It was great to see that this music could be played live given the tuning requirements and intricate rhythms. Indeed, the Keplers provided some of the quietest and coordinated ensemble playing I have experienced. Ustvolskaya’s Second brought down the house. The Duo had primed the audience for her ascetic language. Brutal, energetic and mysterious, Ustvolskaya’s Second is bizarrely scored for solo piano, solo voice, percussion, six each flutes, oboes and trumpets, and single trombone and tuba. Given the ensemble makeup, it was incredibly loud on occasion, the percussionist assaulting two drums with timpani sticks while pianist Drury commandeered the keyboard with fists and forearms. A written description will tend towards the barbaric; however, the symphony is not about noise or force. The vocal soloist declaimed, in Russian, words from the early 11th-century all-around monk Hermann of Reichenau (Hermannus Contractus): “Oh, Lord…” and “True, true, merciful, merciful, eternity, eternity…” Ustvolskaya used his words in her subsequent two symphonies. We suddenly realize the work is about pain and perseverance, and that we are teetering on the edge of a precipice. Cherry fit the role, delivering the aggrieved utterances with intensity. Sometimes it’s nicer not to understand what’s being said. Czernowin’s vision included incorporating folk music, and so The Prince Myshkins, a duet of accordion and guitar, took the stage in two sets (before and after the Ustvolskaya Duo) turning the Harvard stage into a coffeehouse. Addressing the audience directly, they made themselves comfortable with informal patter and social satire. Equally clever and annoying, they sang stories of America’s failed military adventures (in Baghdad and the American Civil War), rambled about artistic dispositions, and lampooned the self-professed need to communicate. As they smugly indicated, often their songs would start in one place and end in another. One could feel the starchy Harvard crowd warming up to them. They closed with a poignant shout out to today’s emboldened High School students. I had not absorbed the printed program ahead of the music – cheers to our long-ago contributor Robert Kirzinger’s detailed notes. The Prince Myshkins reminded me of a musical event I had endured several years ago, and lo and behold, one of the duo, Rick Burkhardt, had in fact been an instigator of that prior calamity.

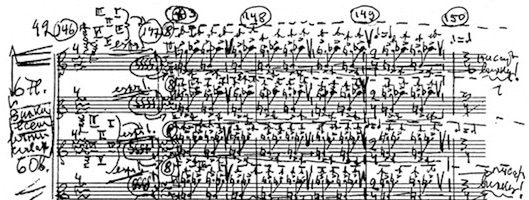

[A detail from the manuscript of Ustvolskaya’s Symphony No. 2 (http://ustvolskaya.org/eng/gallery.php).]

[More Grant Chu Covell]

[Previous Article:

A Catalogue of Darknesses, Part 2.]

[Next Article:

Piano Factory 24.]

|