Thea Kronborg, America’s Literary Diva

|

Ellen MacDonald-Kramer [September 2013.]

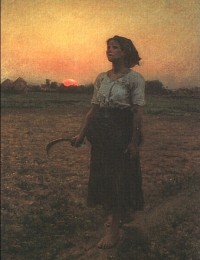

“I only want impossible things. The others don’t interest me… It’s silly to live at all for little things. Living’s too much trouble unless one can get something really big out of it.” So speaks Thea Kronborg, heroine of Willa Cather’s 1915 novel The Song of the Lark. These words, shared with a close friend, give us an immediate glimpse into the strong character of this fictional American diva. Of the few opera singers to appear in classic literature, Thea is arguably the most humanly memorable (not that I’ve anything against Trilby, the title character of George Du Maurier’s Victorian serial: a tone-deaf street waif elevated to operatic greatness by the hypnotist Svengali). But Cather’s heroine has what are perhaps the passionate qualities we might associate with a real-life opera singer. Thea Kronborg’s story is, when viewed two-dimensionally, the typical rags-to-riches tale of fulfilling the American dream. But far from dwelling exclusively on Thea’s journey from small-town Colorado to the world’s major opera houses, The Song of the Lark follows its heroine’s evolution as an artist. Born in the fictional town of Moonstone, Thea is the daughter of a Methodist minister. Although part of a large family, her most satisfying moments are spent on her own, wandering in the sand dunes outside town. She is an outwardly cold, reclusive child, with a nature not even her mother can understand. Her vocal gift is first detected and encouraged by her piano teacher, Wunsch. Thea, however, is sceptical of learning anything in a place like Moonstone. Wunsch is quick to condemn her doubts. “Nothing is far and nothing is near,” he says, “if one desires. The world is little, people are little, human life is little. There is only one big thing – desire.” Following a windfall, Thea goes to Chicago to seriously pursue music. Her new surroundings make her only too conscious of her rural origins and lack of cultivation, and she is plunged into an intense period of self-loathing. Worse, when she returns to Moonstone for a visit, she finds a new and pronounced hostility towards her. Another year of study sees Thea no happier. She is exhausted, depressed, and bitter from what she considers her “fight.” It takes an extended holiday, arranged by her wealthy friend and love interest Fred Ottenburg, to enliven her spirits. For weeks she stays on a ranch in Arizona, exploring the nearby canyon holding the ruins of an ancient city once populated by a people known as the Cliff-Dwellers. The awe she discovers in exploring this ruinous city will have a pivotal impact on Thea’s artistic direction: “The stream and the broken pottery: what was any art but an effort to make a sheath, a mold in which to imprison for a moment the shining, elusive element that is life itself – life hurrying past us and running away, too strong to stop, too sweet to lose? The Indian women had held it in their jars. In the sculpture [Thea] had seen at the Art Institute, it had been caught in a flash of arrested motion. In singing, one made a vessel of one’s throat and nostrils and held it in one’s breath, caught the stream in a scale of natural intervals.” Ten years later, Thea is thirty years old and approaching the height of her career. She has developed into a wonderful soprano but is very much who she ever was. She is still embittered by the shallow artistry of many of her fellow singers. As she tells Dr. Archie, an old friend from Moonstone: “You can’t try to do things right and not despise the people who do them wrong. How can I be indifferent? If that doesn’t matter, then nothing matters.” Cather created a character whose enduring bitterness and disdain make her all the more realistic. Thea’s obsessive, relentless drive, her intolerance for anything less than perfection both in herself and other singers, make her an opera singer we all feel we might know. We can identify equally with her internal warmth and sensitivity. Thea was, in fact, loosely based on the real-life Wagnerian soprano Olive Fremstad, whom Cather interviewed for an article in McClure’s. But Fremstad, unlike her fictional counterpart, was an outright eccentric. To rehearse for her role in Strauss’s Salome, Fremstad insisted on visiting a morgue so she could decide precisely how much she ought to struggle under the weight of John the Baptist’s head. She also kept half of a pickled human head on her piano at home, for the purposes of better understanding vocal anatomy – or for teaching it. Suffice it to say, her students didn’t stay long. The Song of the Lark’s heroine, like its setting and dialogue, may be romanticized (one must consider when it was written). But even in the flourishes there’s a poignant sense of truth, a believable journey for an artist. Here, in Thea Kronborg, is a reigning diva of literary opera singers. [image from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:The_Song_of_the_Lark_%28Jules_Breton,_1884%29.jpg]

[More Ellen MacDonald-Kramer]

[Previous Article:

Chamber ramble with accordion, guitars and percussion]

[Next Article:

Used Bin Troll Tweets C.]

|