To Stand or Not to Stand

|

Anatole Sykley [December 2004.]

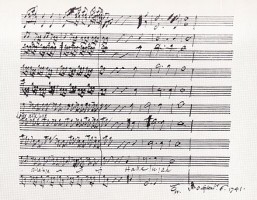

My wife and I revisited Handel’s Messiah by attending the Handel and Haydn Society’s performance under John Finney’s direction this year at Symphony Hall. Mr. Finney is a choirmaster by trade, much in evidence from his deft direction of the choral numbers. The most famous of these, of course, is the “Hallelujah Chorus.” As the music moves into “Part the Third,” a question beyond the control of any conductor intrudes: Should the audience stand? What takes priority, the audience’s desire to follow a tradition, or the chance to hear unimpeded the music’s every bar? Who rules on this stand / no-stand moment, the Hallelujah Chorus Police? At H&H’s Dec. 4 performance, the audience remained seated for about the first 30 seconds. Then a few old folks in the balcony looked around and slowly rose, one or two at a time. Others scattered about stood in imitation, with most everyone else, wearing expressions of insecurity, looking about for guidance. The soloists were clearly amused. Was this audience democracy at work, or did those who stood know something those who remained seated did not? Research into original-performance practice has provided some background. However, the scholarship has not been evenly disseminated among audiences. People still don’t know what to do. Should they respond to the old-time tradition or to Christopher Hogwood’s research, namely that King George never stood in response to the “Hallelujah Chorus”? I am Australian and treasure tradition. I was pleased and surprised when I attended my first Handel and Haydn Messiah in 1984. Americans stood up just as we Aussies and Brits do. Over the past 30 years, I have attended Messiah performances in four countries and have been made increasingly aware that the standing tradition is on the wane. However, in Australia, Canada and Great Britain, in amateur performances in churches and town halls, people still like to stand when the performance is part of a traditional Christmas celebration. Nobody seems to mind the fuss. However, in a professional performance, i.e., where the tickets are expensive, we now tend to remain seated so that the music need not contend with distraction. In London two years ago, at a performance of Messiah in Westminster, nearly all of the audience remained seated. A smattering of old folks stood. Christopher Hogwood, who conducted a performance of Messiah at Symphony Hall a few years back, placed a special note in the program. His research found no basis for the belief that George II rose to his feet. However, here in the US, President Lyndon Johnson, when he saw everyone getting up at the start of the “Hallelujah Chorus,” grabbed his hat and made for the exit. He thought the concert was over. So perhaps in his honor, Democratic voters have reason to stand. Let’s raise our glasses to consistency. Here in New England, of all places, the audience has no reason to respect a tradition that connects to a tyrant. Let New Englanders hear the music, simply and clearly, in all its unmuffled splendor! The chorus’s opening moments are important. They set the mood for the oratorio’s scope. Perhaps the program notes should guide us. If this is about a “seventh inning stretch,” then let it be done consistently. The notes might say something like “The audience should stand at the commencement of the first bar.” This would at least ensure a mercifully brief disturbance, thus avoiding a lengthy barrage of squeaking seats and shuffling feet as happened in Symphony Hall this year. If we choose to remain seated, if this is perhaps the performers’ wish, let the program notes direct. Indeed, this year the H&H’s program went so far as to remind readers to turn the libretto pages quietly. Amen to that. [More Anatole Sykley]

[Previous Article:

Elliott Carter on the Big Screen]

[Next Article:

Early Rehearsal]

|