Unsolicited Remarks

|

Grant Chu Covell [December 2017.]

Helmut LACHENMANN: “… Zwei Gefühle…”; Musik mit Leonardo (1991-92)1; Wiegenmusik (1963)2; Guero (1970)3; Pression (1969-70)4; Ein Kinderspiel (1980)5. Helmut Lachenmann1,2,4,5 (speaker, pno), Lauren Radnofsky3 (vlc), Ensemble Signal1, Brad Lubman1 (cond.). mode 252 (1 CD or DVD) (http://www.moderecords.com/). Even after bumping into derivatives and less artful followers, Lachenmann’s original acerbic brittleness still delights after a long absence. His superbly intense music progresses at multiple planes and rates. The uncanny sounds are not one-off tricks but thought-through conclusions consummately notated. This release is a double treat as Lachenmann appears as speaker in Zwei Gefühle and plays the piano in Wiegenmusik, Guero and the Ein Kinderspiel collection. There are other releases where the composer spits out the abstract phonetic syllables (Accord 204852 [1995], Kairos 0012202KAI [2001] and ECM 1789 [2004]) or strums the keys for Guero (Montaigne MO 782075 [1995], also including Wiegenmusik and Ein Kinderspiel). Guero and Pression are now decades old. Their startling techniques have become overused and their contradictory stances defused. Guero involves touching the keys, the strings and the case. Anything but traditionally depressing the ivories. Starting from near silence, Pression enthusiastically eschews traditional cello sounds and soon lands on excruciatingly coarse grinding before exploring all manner of wrong noises. The children’s pieces are for the precocious child who might not know what to expect from the big wooden box with 88 teeth. They’re actually not for children, but for adults who might remember those early childhood experiences of music creation. Often Lachenmann favors the highest register where pitches compete with the sound of felt-covered wooden hammers striking metal strings. In Falscher Chinese and Filter-Schaukel (False Chinese and Filter Swing) there is the rediscovery that if the hands don’t play together, they can affect the sounds of chords and resonance. [Sticklers for German orthography may note that Wiegenmusik is misspelled on some of mode’s literature for this release.]

“Music of Jonathan Harvey.” Jonathan HARVEY: Concelebration (1981)1; The Riot (1983)2; Cirrus Light (2012)3; Piano Trio (1971)4; Be(com)ing (1985)5. New York New Music Ensemble: Jayn Rosenfeld1,2 (fl), Jean Kopperud1,2,3,5 (clar), Chris Finckel1,4 (vlc), Stephen Gosling1,2,4,5 (pno), Daniel Druckman1 (perc), Linda Quan4 (vln), David Fulmer1 (cond.). Albany Records TROY1566 (1 CD) (http://www.albanyrecords.com/). Harvey’s music demonstrates that rare circumstance where musicians play together but seem to be proceeding independently or at least mindfully apart. Here are five pieces stretching across Harvey’s career, including the solo clarinet Cirrus Light which appears to be among the last, if not the composer’s ultimate work. Concelebration (flute, clarinet, cello, piano and percussion) cycles though material according to a rigorous plan whose changes are heralded by percussion. Familiarity with the map does not help, as Harvey’s content is distracting and compelling. The Riot (flute, clarinet and piano) and the Piano Trio (violin, cello and piano) stand more than a decade apart but both reflect admiration and synthesis of Stravinsky and Messiaen. The Riot was written for Het Trio and explores specific intervals in dedicated sections (thumbs up on the anagrammatic title). There is an unexpected Rachmaninoff-styled frilly parlor music cadence which initially startles though it aligns with the piece’s logic. Becoming balances clarinet and piano.

“WAM.” Michael FINNISSY: Clarinet Sonata (2006-07)1; L’Union Libre (1997)2; Mike, Brian, Marilyn & the Cats (2004)3; WAM (1990-91)4; Giant Abstract Samba (2002)5. Michael Norsworthy1,2,3,4,5 (clar, perc), William Fedkenheuer4 (vln), Michael Finnissy1,2,3,4 (pno, perc), NEC Wind Ensemble5, Charles Pelz5 (cond.). New Focus Recordings FCR157 (1 CD) (http://www.newfocusrecordings.com/). Finnissy’s artful wriggling can infuriate. His flavor of complexity can be mistaken for goofiness. Or maybe, it’s the other way around: Sometimes I don’t mind hearing the story being typed up rather than actually reading it. Until we are told that the Clarinet Sonata’s piano part is derived from Beethoven but played backwards with additional modifications, all we hear is earnest noodling. L’Union Libre asks the clarinet and piano duo also to play percussion, and Mike, Brian, Marilyn & the Cats adds a tape of mewling felines. The schemes that generate the music are obscure and we can only hope the players take some enjoyment in the material. WAM adds violin to the duo, and as the title implies takes Mozart as its starting point even though recognizable pitches and rhythms are rubbed out. The clarinet and violin wander around the stage enhancing the sonic aspect. It is welcome that the Giant Abstract Samba suggests a samba (or any driving rhythmic dance that might include percussion); however, the steam escapes and we are left with a clarinet skating over wind ensemble interjections and other flotsam.

“On the Nature of Thingness.” Nathan DAVIS: Ghostlight (2013); On speaking a hundred names (2010); On the Nature of Thingness (2011). Phyllis CHEN: Hush (2011); Chimers (2011); Beneath a Tree of Vapor (2011). Phyllis CHEN and Robert DIETZ: Mobius (2011). International Contemporary Ensemble. Starkland ST-223 (1 CD) (http://www.starkland.com/). The International Contemporary Ensemble works at new music’s edge, and these two composers may add unusual sound-producing objects for standard ensembles with quirky and delightful results. Several of Chen’s pieces, Hush, Chimers and Mobius, use music boxes and toy pianos to populate a fragile universe. Perhaps the intent is to start from childhood and then grow up. Hush is delicate, but Chimers’ additional violin and clarinet add a disturbed fringe. Beneath a Tree of Vapor adds tape to flute. At 5:27 it’s like a Fabbriciano or Nono piece for instruments and tape delay but greatly accelerated. Davis’ On speaking a hundred names pairs Rebekah Heller’s chocolatey bassoon with disturbing electronic echoes. Ghostlight’s piano is subtly prepared, so when the altered sounds finally appear it is as if the instrument has been hijacked. Composers create music and Davis does that as well, also describing an imaginary space. On the Nature of Thingness is a four-part cantata exploring the nature of text and meaning. Soprano Tony Arnold dances through texts by Zbigniew Herbert, Hugo Ball, Arthur Rimbaud and Italo Calvino in Polish, Dada, French and English.

Morton FELDMAN: Rothko Chapel (1971)1. Erik SATIE: Gnossiennes Nos. 1, 3 and 4 (1891)2; Ogives Nos. 1 and 2 (1886)3. John CAGE: Four2 (1990)4; ear for EAR (Antiphonies) (1983)5; Five (1988)6; In a Landscape (1948)7. Kim Kashkashian1 (vla), Sarah Rothenberg1,2,3,7 (pno, celeste), Steven Schick1 (perc), Sonja Bruzauskas1 (m-sop.), Lauren Snouffer1 (sop), L. Wayne Ashley5 (ten), Houston Chamber Choir1,4,5,6, Robert Simpson1,5 (cond.). ECM 2378 (1 CD) (http://www.ecmrecords.com/). To counteract those who think Feldman is all about tuneless long pieces, send them to Rothko Chapel. However, perhaps not to this particular release. ECM is known for a resonant acoustic, but this recording is astonishingly arid. Furthermore, this performance sounds preoccupied and not contemplative, as if everyone had somewhere else to be immediately after the taping. I prefer the older New Albion recording from 1990 (NA039CD), and not just because Why Patterns? is complementary. There are threads that relate Satie to Cage and thence to Feldman, but here these relationships suggest something solitary and callous. The solo piano pieces enjoin little humor which feels so wrong considering Satie’s whimsical titles and coy Orientalisme, and that we know Cage and Feldman were convivial conversationalists. In a Landscape speeds along without enjoying the view. I did listen to this many times, hoping the different approach would eventually click. The choral pieces, Four2, ear for EAR and Five are polished and the reasons to return. [For Rothko Chapel, I’m enamored of the original LP recording with violist Karen Phillips; ArkivMusic markets a CD of that, For Frank O’Hara and The King of Denmark. W.M.]

“Prayers Remain Forever.” Martin BRESNICK: Going Home – Vysoke, My Jerusalem (2010)1; Ishi’s Song (2012)2; Josephine the Singer (2011)3; Strange Devotion (2010)4; A Message from the Emperor (2010)5; Prayers Remain Forever (2011)6. Double Entendre1: Christa Robinson (ob), Caleb Burhans (vln), John Pickford Richards (vla), Brian Snow (vlc), Lisa Moore2,4 (pno), Sarita Kwok3 (vln), Michael Compitello5, Ian Rosenbaum5 (perc, speakers); Two Sense6: Ashley Bathgate (vlc), Lisa Moore (pno). Starkland ST-221 (1 CD) (http://www.starkland.com/). Some new music can take us back in time. Bresnick operates across such boundaries, but he’s not sentimental. He comfortably rides high modernism but might permit the material to slip into a minimalistic groove (Ishi’s Song, the middle of Prayers Remain Forever) or he may borrow to establish context (emulating Bach in Josephine the Singer). The oboe quartet, Going Home – Vysoke, My Jerusalem, expands from single unison notes, and Bresnick recalls learning to play the wind instrument as well as conversations with his grandmother who mourned relatives that had been murdered back home in Russia. The title piece, Prayers Remain Forever, closes the collection. Cello and piano consider a small handful of themes centering upon a keening, two-plus-three rocking pulse. Josephine the Singer and A Message from the Emperor realize fanciful Kafka stories. The former is for solo violin, the later for two speaking percussionists. The violinist does not talk but represents a legendary singing mouse whose transcendent abilities call into question the symbiotic relationship between artist and audience. The percussionists illustrate the story of a dying leader who bequeaths a cryptic message which, owing to crowds and bureaucracy, will never be delivered. Ishi’s Song and Strange Devotion are solo piano works. Bresnick was taken by a brief recording of a song made by Ishi, the last surviving member of the Yahi-Yani, a Native American tribe of Northern California. The pianist sings the several-second tune and then embarks on a complex, predominantly pentatonic gyration through the tune’s pitches. We may have a few seconds of Ishi’s music, but we don’t know what it means. Strange Devotion for piano translates a Goya etching.

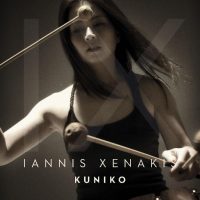

Iannis XENAKIS: Pléïades (1979); Rebonds (1989). Kuniko (perc.). Linn Records CKD 495 (1 SACD) (http://www.linnrecords.co.uk/). I want to like every Xenakis recording I hear, but Kuniko’s overdubbing has squelched much spontaneity and risk. Xenakis’ music is hard. When an ensemble tackles it after extensive preparation, there is always the slight but improbable chance that it may come loose and crash. There was no chance of that happening here. (Of course no one would release a collapsing recording, but we want to hear energy and spontaneity.) Yes, Kuniko demonstrates skill, but the safety net is wide and omnipresent. The execution is consistent in attack and dynamic. This release can pair with the similarly frustrating MIDI realization of the keyboard works on NEOS 10707. The Rebonds pair works because there is just the one player manipulating the battery of objects. Kuniko takes the less familiar movement order, A followed by B.

[More Grant Chu Covell, Rambles]

[Previous Article:

Used Bin Troll Tweets DD.]

[Next Article:

Tips for Prospective Artists]

|