Varèse, Elgar, and Ferrari

|

Grant Chu Covell [February 2000. Originally appeared in La Folia 2:3.] Varèse I took a bus part of the way home a while back. At one point, the bus had to make room for a fire truck. From where I was sitting, it wasn’t possible to make out where the fire truck was coming from. The siren was insistent, and grew louder, almost uncomfortably loud as the fire truck passed, the siren gently receding. Sirens make me think of Edgard Varèse (1883-1965). It would have been most welcome in Amériques. Varèse, like Webern, is a composer of enormous influence whose complete (and extant) works could easily be performed in one afternoon. (It would be an intense afternoon!) Looking back from this new century, Varèse shines as a lone Franco-American individualist of the last century. He is difficult to pigeonhole, and his music has few successful imitators, yet there are few composers and musicians who do not recognize his widespread influence (Frank Zappa and Charlie Parker among them). In life, Varèse was hardly the loner: he was a warm and generous man and his house in New York City was a frequent stopping place for transcontinental writers, artists and musicians, including such as Henry Miller, Fernand Leger, and Joan Miro. The two standard Varèse biographies are both out of print: Fernand Ouellette’s Edgard Varèse, translated from the French by Derek Coltman (Orion Press, 1968) and Louise Varèse’s memoir, Varèse, (Norton, 1972), which comes up in online book search indexes, but the Ouellette is hard to find. The most recent complete survey of Varèse’s works is Riccardo Chailly’s on London (289 460 208-2). Another less recent and less impassioned survey is Kent Nagano’s two separate Erato CDs (4509-92137-2 and 0630-14332-2). There are also recordings by Pierre Boulez spread across several Sony CDs and Robert Craft’s recordings. Individual works have appeared recently in interesting pairings, most importantly Amériques with Christoph von Dohnanyi and the Cleveland Orchestra paired with music of Ives (London 443 172-2). Any respectable performance of Varèse must have bite. If you’re listening to a recording at home, say to one of the large orchestral works, you want glasses to rattle themselves off the table. There’s not much other music that can be as visceral, angry, and so potent with dynamic extremes. Amériques and Arcana, the earliest extant Varèse works, are both for large orchestra. Chailly expertly presents this music and the Concertgebouw Orchestra plays confidently. It’s instructive to compare Chailly’s and Dohnanyi’s Amériques. Chailly’s Amériques comes across as very measured and stately, but doesn’t have any of the restrained passion and intensity of Dohnanyi’s recording with the Cleveland Orchestra. Dohnanyi’s Varèse is surgically precise, and it is invigorating and incredible to hear Varèse in this way. The Cleveland brass is not blurry or mushy, every note and timbre is distinct, and the wind intonation is superb. Nothing sentimental here. Dohnanyi’s Amériques is paired with Ives’s Symphony No. 4 and The Unanswered Question. Chailly presents Amériques in its original version for gigantic orchestra and there are audible differences in texture and material compared to other recordings. Chailly underscores the French heritage of Varèse by emphasizing certain textures and gestures, whereas Dohnanyi offers the shiny aluminum American version. Where Chailly really excels is in Varèse’s songs for voices and orchestra (Nocturnal, Ecuatorial, and Offrandes). Other recordings sound like hastily assembled readings convened just to fill out a disc. Chailly reveals a dramatic and operatic side to Varèse, and each song unfolds in compelling sweeps that indicate preparation. Ecuatorial, a Mayan prayer set for bass voice and orchestra, is one such song. There are complicated timbres at work here which are superbly balanced: solo bass voice, orchestra with plentiful low brass, solo piano, and two ondes martenot. The ondes martenot is among the first electronic musical instruments. It’s very rare and Chailly actually substitutes with an unnamed “special instrument,” but the effect is the same. I’m actually not surprised that Chailly’s interpretations of Varèse’s songs are so wonderful and revealing. Chailly’s Das Klagende Lied and Gurrelieder are my favorites of the available recordings. It would be exciting to hear Varèse’s songs paired with Erwartung or Der Wein, or even something by Revueltas. Poème Électronique, weighing in at a mere 480 seconds, is the progenitor of all electro-acoustic music. I’m wary of making a generalization, but Poème Électronique is one of the most powerful and important works of the last century. It was composed for the Philips Pavilion, a structure built by Le Corbusier and Iannis Xenakis for the 1958 Brussels World’s Fair. A recent book, Space Calculated in Seconds: The Philips Pavilion, Le Corbusier, Edgard Varèse (Princeton University Press), documents the structure’s and the music’s creation. Poème Électronique appears on multiple recordings: One Way Records reissue with some of Craft’s classic Sony LP set (A 26791), on Neuma Records first compilation of classic electro-acoustic music (450-74), and remastered digitally on Chailly’s London set. A work for tape sounds essentially the same from recording to recording, so the recording you prefer will take into account what Poème is presented with. Maybe I’m too historically minded, but I prefer listening to Poème Électronique on LP where a touch of surface noise makes the work more satisfying. Oddly, there is no recording of Varèse’s masterpiece with the short piece Iannis Xenakis composed to accompany it, although both are available separately. Xenakis’s work is called Concret PH and is on a CD of Xenakis’s electronic music jointly produced by the Electronic Music Foundation and INA GRM (EMF CD 003). Déserts is the first piece of music to incorporate live instruments with recorded sound. Varèse sanctioned performances of Déserts without the interpolations of organized sound, and there is a Boulez recording (Sony SMK 68 334) which dispenses with the tape part. Déserts is completely different and less meaningful this way, but the “completist” Varèse fan will want to hear it. Chailly teams with the ASKO ensemble for intense performances of Varèse’s works for smaller ensemble, including a riveting Octandre and Ionisation. Octandre, for a mere eight instruments, compels extremes in register and dynamic intensity. Of the recordings of Octandre that are available, only Craft matches the intensity of Chailly. In a recent trip to New York City, I made my to 188 Sullivan St., the house where Varèse lived. He lived there from 1925 until his death in 1965; his wife, Louise, a significant translator of French poetry, continued to live there until her death in 1985. The house looks neat and trim, and the house’s basement windows are visible from the street. Varèse’s studio was on the other side of these curtained windows (there’s a reproduced photo in the Chailly set taken from inside of the room looking out). There is a modest shiny plaque on the house indicating its famous residents. Nothing about the neighborhood indicates the legacy of sound and energy that passed through that house. Elgar

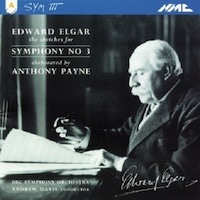

Elgar’s Symphony No. 3, reconstituted by Anthony Payne, is performed valiantly by the BBC Symphony Orchestra with Andrew Davis on an NMC CD (NMC D053). History will tell whether Payne has done for Elgar’s Third what Deryck Cooke did for Mahler’s Tenth. To his credit, Payne had less to go on than what Cooke had; Mahler’s Tenth is in complete short score, Elgar’s Third is pages of sketches, only a few completely orchestrated, the rest merely melodic lines. Elgar’s Second Symphony has always marked a highpoint of English symphonic music to me, few other English symphonic essays have sustained my repeated interest (Robin Holloway and Nicholas Maw do come close), and it’s good to have this music regardless of its provenance and verity. Ferrari Luc Ferrari (b. 1929) is a distinctive French composer who is refreshingly hard to characterize. Most liner notes can’t help but use “mercurial” to describe Ferrari. You will find instruments and voices in his work, sometimes instruments and voices are joined with tape, and sometimes there is just tape alone. Ferrari has also produced television documentaries about the rehearsal process of music by Messiaen and others (Ferrari crossed the Atlantic in 1955 to meet Varèse, and one of his video documentaries is about Varèse.). Ferrari enjoys being a composer. He loves to put something in front of an audience and wait for responses. He clearly relishes those moments where he has our attention and he has the chance to utter profundities or to say nothing. Titles may offend or actually be meaningless or misleading, and some might find his music outright tedious, pointless, or insulting. This is music that confronts, but gradually reveals sly humor and intellect, and enormous compositional technique and skill. Ferrari will go down in the history books as a master of using pre-recorded tape with instruments. Two recordings with works which are classics: Programme Commun for harpsichord and tape (1972) on ADDA 581233, and the classic musique concrete Presque rien No. 1, ou le lever du jour au bord de la mer (1967-1970) on INA GRM 245172. The disc titled “Luc Ferrari: Matin et Soir” (ADDA 581156) with the orchestral composition Histoire du plaisir et de la desolation (which won the Prix International Serge et Olga Koussevitsky) would be on my desert island list. Over the last year, there have been a handful of CD releases of Ferrari’s music, some are reissues, and some are new recordings. The most promising new release is on mode (mode 81), the first in a series of discs devoted to Ferrari. Considering mode’s other series of Cage, Feldman and Xenakis, this is one of those labels where it’s worth acquiring one of everything. Chansons pour le corps (1988-94) is based on a bizarre concept: Ferrari takes a tape recorder into a public park and randomly asks women to describe intimate parts of their bodies. The women’s words are transformed into texts by Collette Fellous, and Ferrari adds tape, a voice, and a few instruments. Chansons pour le corps is paired with a work that won the Prix Italia 1987, Et si entiere maintenant… (1986-87) (which also appears on ADDA 581079). The sounds of a boat, an orchestra and a spoken text, create a journey that never happened. Everything was recorded, then treated as musique concrete, so the entire work has a surreal mystical quality. The listener becomes accustomed to the sounds of the ocean or of an orchestra, and then suddenly they are chopped up, forcing the listener along through Ferrari’s narrative. From Auvidis Montaigne (another label worth acquiring, one of everything) comes a CD of Ferrari’s piano music (MO 782110). Piano music is not really representative of what Ferrari is about, so this disc is best for the diehard Ferrari fan. Some short piano works date from the 1950’s, reflecting Ferrari’s somewhat simultaneous mastery of serialism and its abandonment for more chance related processes. The largest works on the disc are from the 80’s and early 90’s and are grand, introspective pieces. There are echos of Histoire du plaisir et de la desolation in these later works. From Tzadik comes Cellule 75, force du rythme ou cadence forcée for piano, percussion and tape (1975) and Place des Abbesses (1977) for tape alone. Cellule 75 is a mesmerizing half hour of somewhat static music for piano and drum over a gradually changing tape. There are seemingly irrelevant interruptions (marching band music) that cut up the flow, and somewhere along the way it seems as if the tape moves from accompaniment to foreground and the piano and percussion become ineffective commentary. Maybe it’s the duck noises. William Winant and Chris Brown are featured. Realized at Ferrari’s home studio, Place des Abbesses is an evocative portrait of a neighborhood in Paris, “between the Sacred Heart of God and Saints, and the Pigalle of license and sex. Nice place, a little quaint.” (Cellule 75 with different performers is also on ADDA 581010). On Blue Chopsticks, Interrupteur, for 10 instruments (1967) and Tautologos 3, for 11 instruments and tape (1970) are re-issued from an EMI LP featuring Ensemble Instrumental de Musique Contemporaine de Paris under Konstatin Simonovitch. In Interrupteur, we have a slow moving background, instruments glitter and time moves slower. These pieces are concerned with notation and improvisation, common themes back when they were written. Tautologos 3 incorporates tape recordings of the same piece which are folded in against itself. Large cycles of isolated notes cross and intertwine creating a vast and seemingly endless texture. There are occasional punctuations of all the instruments together as a well as some seemingly non-sensical interruptions (which are really the slow cycles played much faster, though one sounds like a European ambulance). Despite the randomness, the musical material is very engaging. There are few works that would constitute the essential Ferrari, and mode’s series will hopefully come close. The interested listener is encouraged to pick up the new release on mode and either ADDA recording with Programme Commun, or Histoire du plaisir et de la desolation.

[More Grant Chu Covell, Vol. 2, No. 3]

[Previous Article:

Music as Search and Discovery]

[Next Article:

Dear La Folia 1.]

|