Walt’s Ratatouille 4.

|

Walt Mundkowsky [August 2001. Originally appeared in La Folia 3:4.]

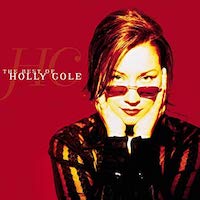

The Best of Holly Cole. Cole, vocals; Aaron Davis, piano; David Piltch, bass; others. Metro Blue 7243 5 29064 2 0. Cole’s highlights package hasn’t been assembled with great care, but it does lend an old fan the excuse to spill some opinions. At the start, it was the Holly Cole Trio. The clean piano-bass backing propelled her smoky alto in smart, refined cabaret fashion. An offbeat Tom Waits tribute, Temptation (1995) deserves wide currency (not least for its powerful bass, unusual on such discs). After that, Cole added guitar and drums to the lineup, which sucked some of the space and complexity from her approach. Best of ignores Girl Talk (her debut), but otherwise focuses on earlier stuff. Blame It on My Youth (1991) gets three nods, and Don’t Smoke in Bed (1993) four. The tracks from Temptation are iffy. “Jersey Girl” scores with the promise Cole sees in the line “Well I’ll take you on all the rides,” but outstays its welcome. (A country-inflected “[Looking For] The Heart of Saturday Night” and “I Don’t Wanna Grow Up,” in which paralyzing dread replaces the original’s high spirits, would be my choices.) Played live by the augmented band, “Train Song” comes off loose and obvious, and “I Want You” is minor at best. For me, Dark Dear Heart (1997) is an unwelcome move into pop, but “I’ve Just Seen a Face” (included here) is wittily bent into a stalker’s anthem. My favorite Cole performance — Elvis Costello’s “Alison” — concludes matters. It’s been available via Japan (Yesterday & Today, 1994), but not on a U.S. album. The version on Costello’s 1977 debut has been called “stripped down,” but this appears skeletal beside it. Pianist Aaron Davis obsesses over the melodic cell, but stays perfectly aligned with Cole, whose chill and sadness never dilute the song’s homicidal air. Her delicious point-making (the hardened tone on “friend,” that lingering s on “sticky”) and daring legato climax are fully integrated elements. I should carp about the 46:48 timing, but “Alison” provides 203 splendid seconds.

Barry Guy (b. 1947) could keep busy as a virtuoso free-jazz bassist, but he’s also drawn to composing. Here, then, is a quartet of Guys: Patrick DEMENGA / Thomas DEMENGA: Lux aeterna: Music for two cellos. ECM New Series 1695 289 465 341-2. The Demenga brothers commissioned Guy’s Redshift (1998), and it’s the most kinetic and varied entry in this uneven program. (The title indicates Doppler effect among photons of light.) Soft rhythmic strumming opens and closes the piece, while the second cellist plays a penetrating drone or (later) a steady, rising melody. The action often involves one cello influencing the other, but Guy maintains differences with clear-cut motion and phrasing. His scenario is gripping — angry sawing, flurries, pizzicati against high harmonics, scraps of song, slides. Lasting 14:11, Redshift encourages repeat hearings. Maya HOMBURGER / Barry GUY: Ceremony. Homburger, violin; Guy, bass. ECM New Series 1643 453 847-2. Along with his more prominent jazz gigs, Guy played in The Academy of Ancient Music under Hogwood. Homburger is an exponent of the Baroque fiddle and stick (and student of Eduard Melkus) who’s open to improvising. Their oddly appealing Ceremony displays all these currents, without attempting a synthesis. Homburger and Guy begin as they often do in concert, with the Praeludium from the first of Biber’s Mystery Sonatas. (Melkus’ landmark 1967 reading of the cycle [a midprice DG Archiv set, 453 173-2] remains wholly persuasive.) The violin figures represent the angel Gabriel’s rustling wings, and Homburger’s light, rigorous touch casts a spell. Celebration (1995), Guy’s first for her, gets us out of 1676 Salzburg by employing the modern toolkit. At journey’s end, the vapor-trail harmonics are lovely. (His own solo wouldn’t look out of place in the Parker-Guy-Lytton trio.) The strongest item is the title cut, where Homburger fronts a squadron of violins on tape. It takes a typical route (call-and-response or simple imitation), until she soars away from a choir of her canned selves. Such magic summons Berg citing Bach’s Cantata 60 in his Violin Concerto. Immeasurable Sky and Breathing Earth (the duos) are cogent and colorful, but less ambitious. This isn’t Biber (plentiful enough right now), but it’s much too sophisticated to reside in Crossover Land. Peter KOWALD & Barre PHILLIPS, Barry GUY, Maarten ALTENA: Bass Duets. Free Music Production FMP CD 102. Extended playing techniques are an important facet of Guy’s chops. They get to shine in these 1981 duets with Peter Kowald (round two of a strenuous avant-garde tournament). Das Schweigen [Silence] von Marcel Duchamp introduces and revisits a spectrum that evades categories. (As Alex Ross said of a Lachenmann cello work, “At times it sounds as though six or eight hands are attacking the instrument, not all of them human.”) Bows can turn into drumsticks, engaging in spooky effects à la Penderecki or a contest of ping-pong beats. Anything approaching the conventional gets twisted; low notes grind or lose momentum (and tone), and pizzicati snap. Paintings (19:12) conducts a richer dialog, since tonal beauty (however threatened) gains a rôle. The initial image is Japanese ritual — well-spaced plucks and thumps. Guy’s rapid fingering announces a haunting episode; over his broad bowing, Kowald floats a delicate tune. Gradually they converge, and the pure harmonies suggest piping recorders. Insectile activity punctures the mood. The initiative passes back and forth, as they use everything in Schweigen and more. The pull of that lyrical passage surfaces, however, and its reprise makes an eloquent finish. This 1999 disc is classy all around — bracing Arakawa design, Jost Gebers’ close but not cramped miking, and Kowald’s personal notes. (The bassist is a luminary in New Music circles. Next time I’ll address his Duos: Europa-America-Japan [FMP CD 21], a musical diary from the latter ’80s.) HOWARD RILEY TRIO: Synopsis. Riley, piano; Barry Guy, bass / bass guitar; Tony Oxley, drums / electronics. Emanem 4044. I grabbed this partly out of nostalgia, having known the 1974 lp while in London. Maybe I’m obstinate, but it still seems valuable — mostly quiet music that’s sinewy and subtle. Mandrel establishes the pattern. After a unison crescendo, Guy’s solo flight kicks things along, as one mode — bowing, plucking, or striking — flows into the next. Similarly, the trio’s discrete gestures form an unbreakable thread. (Slow sections bear the imprint of the creepy “Night Music” in Bartók’s Out of Doors suite.) Sirens hits harder (Riley’s single strokes, Oxley’s crashes, Guy scraping away at clamped strings), as the musicians cling to repetition or exchange Morse-code replies. An extended jam sends Quantum on a wild (but not very distinctive) ride. Guy switches to electric bass for Ingot, to exploit its pedal-generated timbral distortions. This urges Riley to extract waves of sound from the piano’s insides, while Oxley adds electronic noise among his drum rolls and junkshop percussion. The 18:18 Runes (from the same session) has been added for CD; it puts all the previous impulses into an unbroken span. At 26, Guy had attained mastery — luscious singing tone as well as impeccably carved tremolos. (Kowald remembers, “Sometimes I wanted to be as fast as him; I never made it, though.”) Margaret Steven and Sheila Fraser’s taping won’t spur one’s inner audiophile, but it copes decently with the range of sonorities. (Oxley’s hot cymbals and heavy “bombs” overload the setup now and then.) Each number (a mix of standard and graphic notation) received only one take, no overdubs. In the evening, the group moved to another studio to perform on a different Emanem release.

Alban BERG / Anton von WEBERN / Erich URBANNER: Works for String Quartet. Alban Berg Quartet. Teldec 3984-21967-2. When I viewed the Arditti Quartet’s reissues of Berg (3:1) and Webern (3:2), I also tried the other end of the telescope. This 1974-75 disc (essentially the ABQ’s first two albums) would have ranked high among the alternatives. The group name suggests a commitment to Berg’s ethos, and the performances boast exacting ensemble and intonation allied with deep tonal resources. (A smooth blend can launch ponticellos that cut to the bone.) Berg’s Lyric Suite had become the ABQ’s signature piece, and they grasp its brilliance, disquiet, swagger, and desolation. (Their 1992 remake [EMI CDC 5 55190 2] is a bit more settled, with no loss of intensity.) Webern’s “official” quartets (Op. 5, 9, and 28) are intriguingly rendered — as alert to detail and nuance as the Ardittis, but applying a weightier palette. The brief Third Quartet (1972) of Erich Urbanner recalls Schoenberg’s late method. The ABQ gives it their all, and it truly sizzles. In their day, these recordings sounded superb and they’re still acceptable. The balances tilt upward, which can impart a glare to Günter Pichler’s lead violin not evident live, and cellist Valentin Erben sometimes recedes a tad. Still, this CD contains 77 minutes of core repertoire smashingly done. (Available from Berkshire Record Outlet [www.broinc.com] for $7.99, or via Amazon.de. NorthCountry handles the Emanem and FMP labels.)

[Previous Article:

A Cornucopia Of Great Verdi Singing: Les Introuvables Du Chant Verdien (Rarities Of Verdi Singing)]

[Next Article:

Piano Diary 4.]

|