Zweiter Spaziergang mit Rücklauf

|

Dan Albertson [January 2009.] [With customary appreciation for the efforts of Bettina Tiefenbrunner-Horak and for the gift of G.C.C. — D.A.]

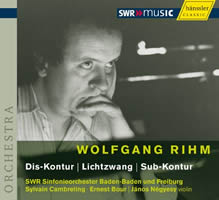

Wolfgang RIHM: Dis-Kontur (1974, rev. 1984)*; Lichtzwang (Musik in memoriam Paul Celan) (1975–76)**; Sub-Kontur (1974–75). János Négyesy (vln)**; SWR Sinfonieorchester Baden-Baden und Freiburg, Sylvain Cambreling*, Ernest Bour (cond.). hänssler CLASSIC 93.202 (http://www.haenssler-classic.com/). Distributed in the US by Allegro Music (http://www.allegro-music.com/). Each of the three works on this disc was written soon after the composer’s brief apprenticeship with Stockhausen and when Rihm was between 22 and 24. In retrospect, they seem brash, buoyant and piquant, a composer striving for a voice, but in them are many characteristics of later Rihm as well, foreshadowing his love of the primacy of rhythm and of darkly hued instrumentations. Dis-Kontur makes quite a jolt upon its entrance: Bass drums and timpani are unaccompanied for almost four minutes. Later the percussive palette expands to include prominent snare drums and a fleeting piano on occasion before a surprising cadenza for cymbals. The range of orchestral writing for 90 players is broad, but contemplation is an endangered species here. Overall, I sense that the piece is a march of sorts, not unlike Lachenmann’s Fassade from the previous year, but in its sustained assaults sounding closer to Xenakis. This recording is the only “modern one” on this CD, dating from earlier this decade; what is unknown is which version of the score was used or indeed how substantial the 1984 revisions were. Lichtzwang (Musik in memoriam Paul Celan) is less a concertante work than a studied dialogue. This recording was made mere weeks after its Royan première and is very clear; the then-young Négyesy is now a San Diego-area fixture and still as able. Here is another percussive opening, with cymbals and tam-tams, yet the work’s most beautiful moments are found when the flutes and piccolos meld with the solo textures. The piece survives on an extremely threadbare palette and in high registers for much of the time; not even the presence of four clarinets and four bassoons (no violins apart from the soloist) could add much menace. Sub-Kontur is another vintage recording, captured days before the work’s Donaueschingen première. This piece may be the richest of the trio, in some ways a grand adagio in continuation of the Mahler-Berg line, most of all in the strings midway and in the brass before the coda, but the discourse is hampered by too much bustle, including another percussive onset. More creative orchestral staging is at work here: Of the winds, only three contrabassoons remain and the brass section is larger than usual, while a few solo piano moments convey a chamber setting at odds with the remainder of the piece. Moving forward, two recent Rihm works occupied my attention during this time, his Zweiter Bratschenkonzert (Über die Linie IV) (2000–02) and Canzona per sonare (Über die Linie V) (2002). The former was a great disappointment because its marvelous predecessor, Rihm’s first viola concerto finished in 1983, was one of the works that heralded his maturity and even now is an intensely moving experience. Two decades onward, Rihm has opted for a piece with none of its forbear’s range of emotion, staying comfortably in quiet dynamics for some 33 minutes, almost without cease. Percussion injections are subtler here and the textures more amorphous, less focused; even soloist Tabea Zimmermann is left without much memorable to play. Perhaps the spectre of his earlier achievement scared him in a new direction and while a clone would have been a letdown as well, I expected more. The latter work, featuring two of Bruckner’s preferred bass Wagner tubas as well as a ripieno group split into two camps, is only half the length and much more varied, with some snarling brass interchanges and almost filigree solo passages from the piece’s soloist. I should note that Rihm here requires the rare alto trombone, an instrument once ubiquitous in Baroque times, but I am sure never used as brusquely as in this work. For a score whose combined instrumentation resembles a modest symphonic band, the results are dazzlingly variegated. Rihm has written a showy piece for Michael Svoboda without forgetting to make the ensemble parts noteworthy or the solo part soulful as well as passionate.

[More Dan Albertson, Spaziergänge]

[More

Rihm]

[Previous Article:

Three, by Two]

[Next Article:

Mostly Symphonies 9.]

|